One of the beautiful things music can do

Teaching music inside San Quentin

by Alex Heigl

Every California correctional institute exists under the long shadow of Alcatraz. And thanks to Johnny Cash, Folsom State Prison is part of the global vocabulary too. Then there's the relatively-recently-renamed San Quentin Rehabilitation Center, about a half hour north of San Francisco, the oldest such facility in the state.

From the start, San Quentin was a grim preview of how America's carceral system (and in particular, California's use of inmate labor) would evolve. It was built in 1854, by prisoners naturally, out of timber from the state's actual first prison, a 268-ton wooden ship anchored in the San Francisco Bay. As if that weren't too on-the-nose, San Quentin actually pre-dates California's Capitol building, our roadways and public colleges and universities, as well as the founding of nineteen other entire states.

Things didn't get better inside over the decades. Bedlam-esque living conditions prevailed, torture as an interrogation technique persisted into the 1940s, and a racist, pro-sterilization "doctor" named Leo Stanley spent decades there happily pursuing a bizarre fixation on testicular grafting to the tune of 10,000 or so operations. San Quentin was, for decades, also home to the largest death row in the country.

The facility's pop-culture presence includes two separate Humphrey Bogart movies where he plays an inmate, Jack London's last book (about astral projection), Metallica's 2003 St. Anger music video, and the Nickelback song San Quentin, inspired, incredibly, by Chad Kroeger meeting the prison's warden at Guy Fieri's birthday party. (Skip to 7:37 to hear Kroeger really lean into the Italian pronunciation of "Fieri.") It was also the site of Johnny Cash's first prison concert on New Year's Day 1958, an event that a 20-year-old Merle Haggard witnessed and would later credit as his inspiration to become a musician.

I'm fairly sure the St. Anger video was my actual introduction to San Quentin. As a huge dork, I find that video fascinating: It's the first time we see bassist Robert Trujillo with the band and the first time a weary post-9/11 United States heard drummer Lars Ulrich's new, improbable snare drum sound. There's a whole separate conversation about the use of incarcerated people as part of Your Band's Brand, but Metallica did return after filming to perform a proper concert, and there's footage of James Hetfield delivering a seemingly heartfelt speech to the inmates in the Metallica documentary Some Kind of Monster.

All these years later I now associate the notorious prison with a different kind of music. My employer the San Francisco Conservatory of Music has for several years now partnered with the organization Musicambia to send students (under the supervision of a voice teacher, Matthew Worth) to San Quentin for a three-day songwriting workshop with the incarcerated men.

Opening the list of post-workshop comments shared with us via Musicambia by the incarcerated people who took part, this one was right at the top:

"Musicambia taught me what love and magic really mean," one said.

[More of their quotes throughout.]

"I loved being able to meet the students and share ideas with them. My team/group had a full-on band with a rhythm, string, guitar, and brass section. This experience was beyond anything I could ever do by myself on my computer. It inspired me to become a teacher someday because I love sharing my experience and knowledge."

The organization was founded in 2013 by Nathan Schram, a two-time Grammy-winning violinist and composer/arranger. Growing up as a military brat, Schram said his parents always prioritized finding him some kind of ensemble to play in whenever they moved, which led to him eventually realizing the value of the role music plays in social connections. Through Ensemble Connect, a post-grad program associated with Carnegie Hall and The Juilliard School, Schram wound up playing a concert at New York's own infamous prison Rikers Island, which he now calls "the most meaningful performance I'd given up to that point in my life."

Concurrently, Schram's brother and sister, both public defenders, were inflection points to his understanding of our grotesque carceral state.

"This is an evil in our society," he said. "What we do to incarcerate more people than any other country in the world, how we do it to them—none of it is making us a better society."

Schram took Venezuela's El Sistema program, a government-funded music education initiative founded in 1975, as one of his models, and he became the first American to visit Venezuelan prisons with núcleos (full-fledged music schools operating within the country's notorious prisons.) "It was this perfect thing to present to adults hungry for an opportunity to change or to find some sort of way of getting through the intensely horrible situation they were in," he said.

Musicambia's pilot program began at New York state's maximum-security Sing Sing Correctional Facility. Ensemble Connect helped Schram sort out the red tape, and he raised funds to buy as many instruments as he could. It was the beginning of a program that now has a massive waitlist of inmates seeking to join, and has since expanded to Kansas' Lansing Correctional Facility and San Quentin.

"Musicambia was one of the most prolific, spiritual experiences in the discovery of my musical abilities and the power of community in the development of sound that amplifies one's soul."

Voice teacher Matthew Worth got involved in the program in 2020, which is now in its fifth cycle after a year off due to Covid. Aided by bassoonist Brad Baillet, another of Musicambia's roster of teaching artists, the actual instruction that he and the assisting music students do spans from songwriting to more advanced classical-style composition to general technique, whether that's on an instrument or voice.

The range of music Worth and the students encounter includes your sort-of expected genres like hip-hop, country, and metal (Musicambia Executive Director Shawn Jaeger said that Lansing in particular is home to a large population of shredding guitarists). While many of Musicambia's teaching artists do come from a classical background, nobody is pushing that on students.

That said, "there are people who are genuinely interested in [classical] and have really taken to these opportunities that are kind of more familiar to folks who have gone through a conservatory training program," according to Jaeger .

Case in point is one San Quentin musician that Worth sees each year named Brian Conroy.

"Brian is one of the musicians who came to us with a background in instrumental Western classical music," Worth said. "So he had this great opportunity for him to workshop music with conservatory musicians who could sight-read and play his work."

"The first year Brian had a small bassoon and trumpet piece," Worth remembers. "This year he came to us with a full-on octet written for two trombones, a couple of trumpets, bassoon, percussion. It was well-written, with some minimalism-esque repetition of certain lines within the confines of the meter. It was like playing down a movie score. So what we've seen is this encouragement for the incarcerated guys to have their creative energy encouraged and grow in between our visits." (Another Musicambia student, Joseph Wilson, wrote a full-on opera in prison.)

"I love the times when we look around at each other while the spirit of music is being felt and played. In those moments I feel closest to God and Heaven."

The impact of a session at San Quentin on the conservatory students is immediately apparent. When Worth and I spoke it was the Wednesday after the workshop had wrapped. He told me he had already heard from two students eager to return. "One is reaching out to Brad [Baillet] to see if they could do post-graduation work later this year with him at Sing Sing, and the other one just wrote to me a couple hours ago, 'I can't wait to come back again next year.'"

"Life-changing" was what jazz piano student Abner Sahaid called it. "I cannot express how important it is for these programs to exist," he said. "I made amazing connections with the participants, some of whom opened up about their past with me, which made me believe in second chances and completely go against the way society has painted these men. They had the utmost respect, kindness, and ambition to create art. I would do it again and again and again."

Jazz trombonist Graham Houpt echoed Abner's "life-changing" line, adding, "I'm not sure I've been around any group of people, including at the Conservatory, more excited to create music together than at San Quentin. Nobody there is taking music for granted, something I didn't even realize I was doing until I worked with these amazing musicians."

"By design, we never go and look to see what it is that got them in there," Worth added. "So I only know what I experience for four to five hours, a few days out of the year, [but] every single participant that I've seen has been rehabilitated."

"These guys are outstanding, intelligent, and hoping to be contributors to society. There's nothing that I wouldn't try to do for them."

"When I first came in it was day two and everyone already had been there and they were performing [a song called] 'Light It Up' and I felt something I can't explain. Seeing, hearing and feeling real music live made me understand how beautiful and blessed we are to be able to make music. I now want to pick up an instrument. I'm 21 and have five months left on a two-year sentence."

Program director Shawn Jaeger (also a violinist and composer), was bouncing around East Coast conservatory circles as a professor, and kept hearing from musicians he knew involved with the organization that their favorite teaching they'd done was at Sing Sing. His day-to-day work now includes not only the administrative work of dealing with prisons, but also expanding Musicambia to different regions and securing funds for the non-profit.

"We have a lot of opportunities [for expansion] via word of mouth among administrators," he said. "The Kansas Department of Corrections made a video about our workshop in Lansing, and that's helpful, because the Department of Corrections in another state will care about what another state's DOC has to say."

Asked about the oversight facilities exercise over Musicambia, Jaeger said that "if a student wants to write about their experience of incarceration, we're going to support that and we're not going to censor their voices, and I'm not aware of a facility censoring anything."

"It's more about profanity and certain kinds of words that aren't allowed to be spoken in the facility, not the content or the message. Students will write about all kinds of things: family, heartbreak, healing, and the justice system."

"My favorite part of the program is the development of the random and how that works its way into a symphony of song and sound. It shows me how transformation is always possible when you add opportunity to desire and a pinch of patience!"

I asked Jaeger if there's any concern that the facilities may be using Musicambia's work as free PR instead of instituting real change.

"The Lansing video was an exception," he said. "Typically facilities or the DOC are not advertising the work we're doing."

Jaeger, Schram, and Worth are nice and earnest guys, so when we spoke I didn't want to do the thing I always do which is to say "but is this actually doing anything?" and bum people out. But is this actually doing anything?

Music has, broadly speaking, failed to change the world. It will continue to fail doing that at San Quentin, a place that for decades has been cramming men into cells that, at 48 square feet, are half the size that the American Correctional Association recommends for a double-occupancy cell. Twenty-eight inmates there died of Covif in 2020 after prison officials "ignored virtually every safety measure" in a botched inmate transfer. Four-hundred and twenty-two people have been executed at San Quentin. Razing it and salting the earth seems like a better start to rehabbing it than a music program.

California Governor Gavin Newsom, by contrast, is an oily, well-coiffed, shiny-toothed weasel with his eyes fixed on the White House, and everything he does should be treated with intense suspicion. In 2023 he launched a hundreds-of-millions-costing effort to rehabilitate San Quentin dubbed "The California Model" (despite explicitly being based on Norwegian prisons), which hinges largely on PR from stories akin to Musicambia's. Look, a San Quentin podcast was a Pulitzer finalist! Behold, an incarcerated people-run newspaper won five awards from the California News Publishers Association in 2020! Marvel at the accredited liberal arts college at San Quentin that's awarded over 200 degrees! Inmates and guards play friendly games of chess!

The flip side to the cynic's read though is that you actually do gotta hand it to them in a sense. Even if all of these NPR-baiting breads and circuses are calculated attempts to paper over San Quentin's horrible history and garner California some shoulder-pats for being "progressive," they are still actually happening and affecting the incarcerated men's lives.

I did push Jaeger on whether he feels that prisons are using the work of organizations like Musicambia to distract from the bigger issues they're facing that require real, internal reckoning and work beyond simply opening their doors to external groups.

"There is always this larger issue of whether or not something is contributing to the continuation of a system," he said. "But where we're at is simply that there are people who are incarcerated right now who would benefit from having a creative, supportive musical environment. We do hope that the broader system will become more compassionate, more dignified, more focused on rehabilitation. There's a long way to go there. So we're being practical. There's a need that needs to be served and met right now."

Yet even with innocuous programs like Musicambia, the carceral state will always find ways to inflict 10 percent more cruelty. Jaeger said that one of the most challenging parts of Musicambia's work is losing contact with a student. "If somebody is transferred to another facility, but is still incarcerated, in New York state, as people who go inside correctional facilities, we are not allowed to have direct contact with incarcerated people. So we cannot write letters, we cannot send messages. Meaning that at that point, we essentially lose contact with the participant."

However, in New York, the organization does operate an alumni program Jaeger said.

"People can form bands or do paid gigs with us, and we provide instruments and lessons for people who come home with this idea of continuing the musical community that was created inside on the outside."

It doesn't take a psychologist to understand the benefits of music to the incarcerated men's rehabilitation. Reflecting on the process of bringing a song to completion, one man said, "It helped me with patience and hard work and realizing that I can make it pay off in the end with determination." Another simply wrote that Musicambia "helped me to grow in my goal of building a better relationship with my musician father."

Though Musicambia doesn't directly involve itself in the parole process, Jaeger said they work with other organizations like New York's Parole Preparation Project to share materials that can help their students with that.

"There's a real power in seeing somebody express their feelings through music, and that can be a really valuable component of the parole process. We'll share videos, so the parole board is getting to see somebody in their best light. They're collaborating and showing their humanity in all its complexity. That's one of the beautiful things music can do."

Alex Heigl is a writer and musician living in San Francisco. He spent 10 years and change in Brooklyn playing a lot of music and writing for People Magazine, Entertainment Weekly, and Page Six, because that's where the money was. Here's all of his music and some moderately interesting stories.

Support our work here with a subscription

A piece of mine from A Creature Wanting Form.

And one from We Had It Coming.

More on prisons in Hell World:

An interview with Empowerment Ave, a group connecting incarcerated writers with journalists on the outside to help them pitch, edit, and get paid for stories published in mainstream publications.

An excerpt from The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration (PM Press), a clear and concise overview and granular look at the sheer brutal scope of "the largest system of incarceration in human history," and the economic and political machinations that have gotten us to this low punishing point.

A piece about "pay to stay" rules which exist in 40+ states, where inmates are charged up to hundreds of dollars a day for room and board. Sometimes, like in Florida, they're charged for their original sentence not the time they actually serve.

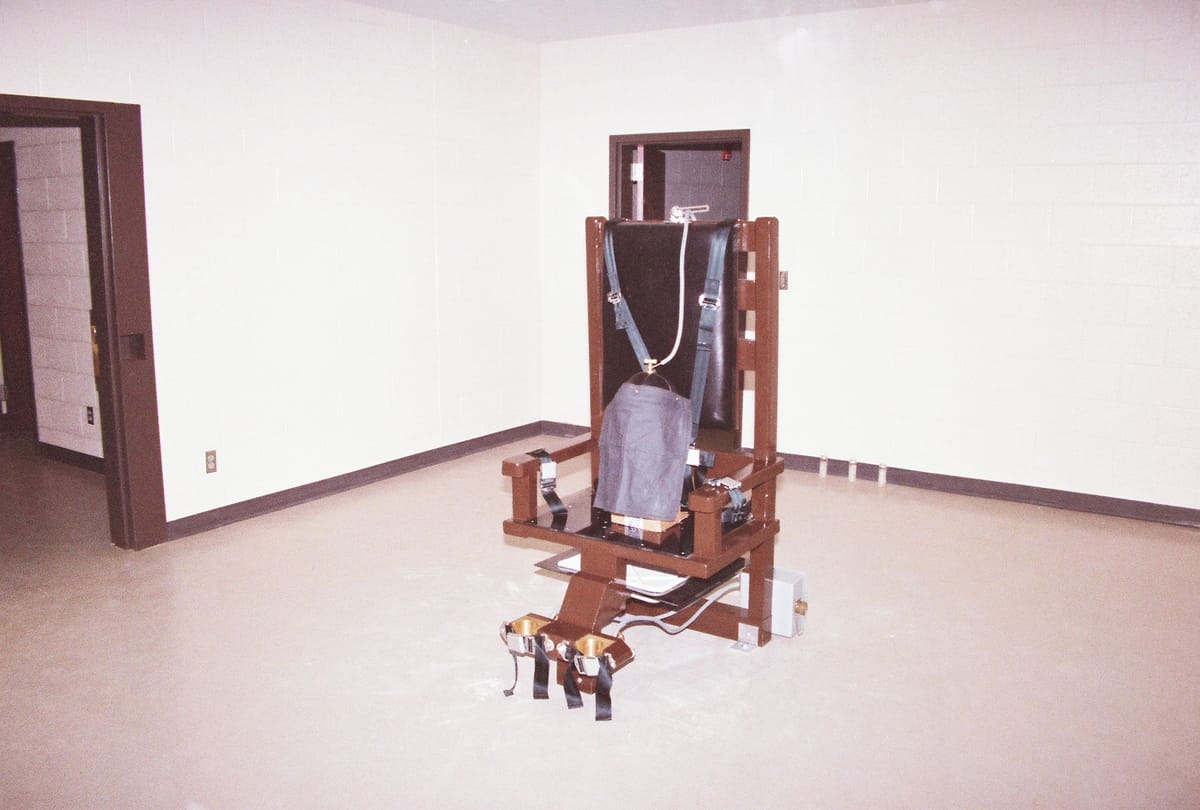

On the death penalty in South Carolina, and an interview with Fred Leuchter the now discredited architect of execution devices that were in use throughout the country for decades.

More on the death penalty, and the last person to be executed by firing squad in the country.

Here's one about prison gerrymandering.

Pretty slick shit right? First you arrest predominantly Black people from large population centers that tend to vote Democrat. Next you cage them in more rural places where the prisons are thereby inflating that district’s raw representational power. Now areas who rely on prisons for jobs and power and wealth can have a leg up on passing legislation that will send more Black people into those same prisons in a massive feedback loop of disenfranchisement.

On Corizon Health, a massive private company that has revenues of $1.5 billion a year, offering really shitty health care to incarcerated people in dozens of states. By providing less and worse health care than inmates need they get to pocket more of the tens of millions in state contracts we give to them. And because they sometimes stiff the medical vendors they work with a very cool thing is that inmates are getting bills and chased down by creditors for medical care they received while in prison.

A public defender in New York City on the “squalid conditions" "rampant violence" and "a lack of essential services such as food and water..." inside, and the case for burning Rikers to the ground.

On "looting," what happens to prisoners during floods, and our nation of snitches.

"In our nation of snitches informing on our fellow citizens isn’t just an unfortunate responsibility of our daily lives it’s been elevated to a patriotic and moral duty."

Here's an older one about the disgusting unsanitary conditions in a New Jersey prison being paid millions by ICE to hold detainees.

An interview with a public defender in Ohio about the pressures and satisfactions of defending people who a lot of times no one else in the world gives a fuck about.

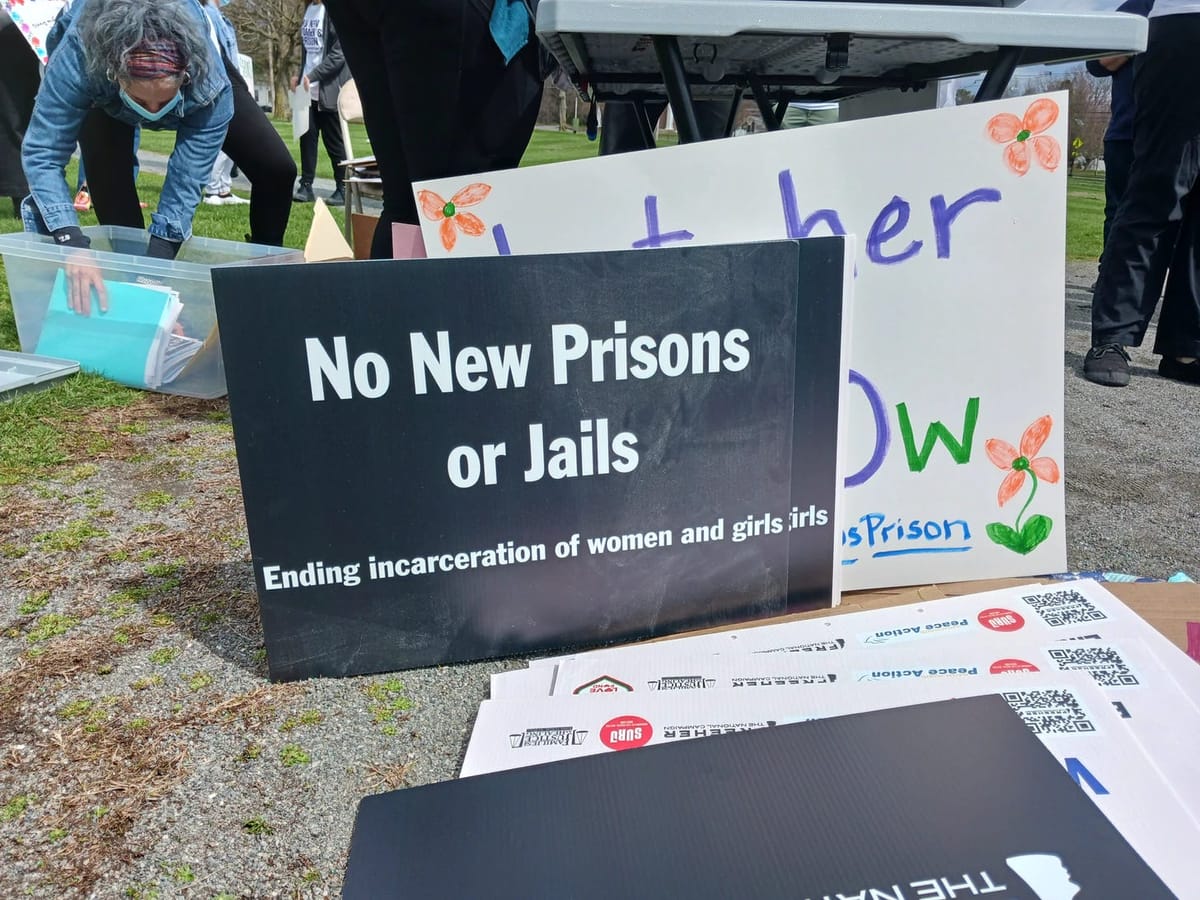

A dispatch from an anti-carceral protest in Massachusetts against the proposed construction of a massive and expensive new women’s prison.

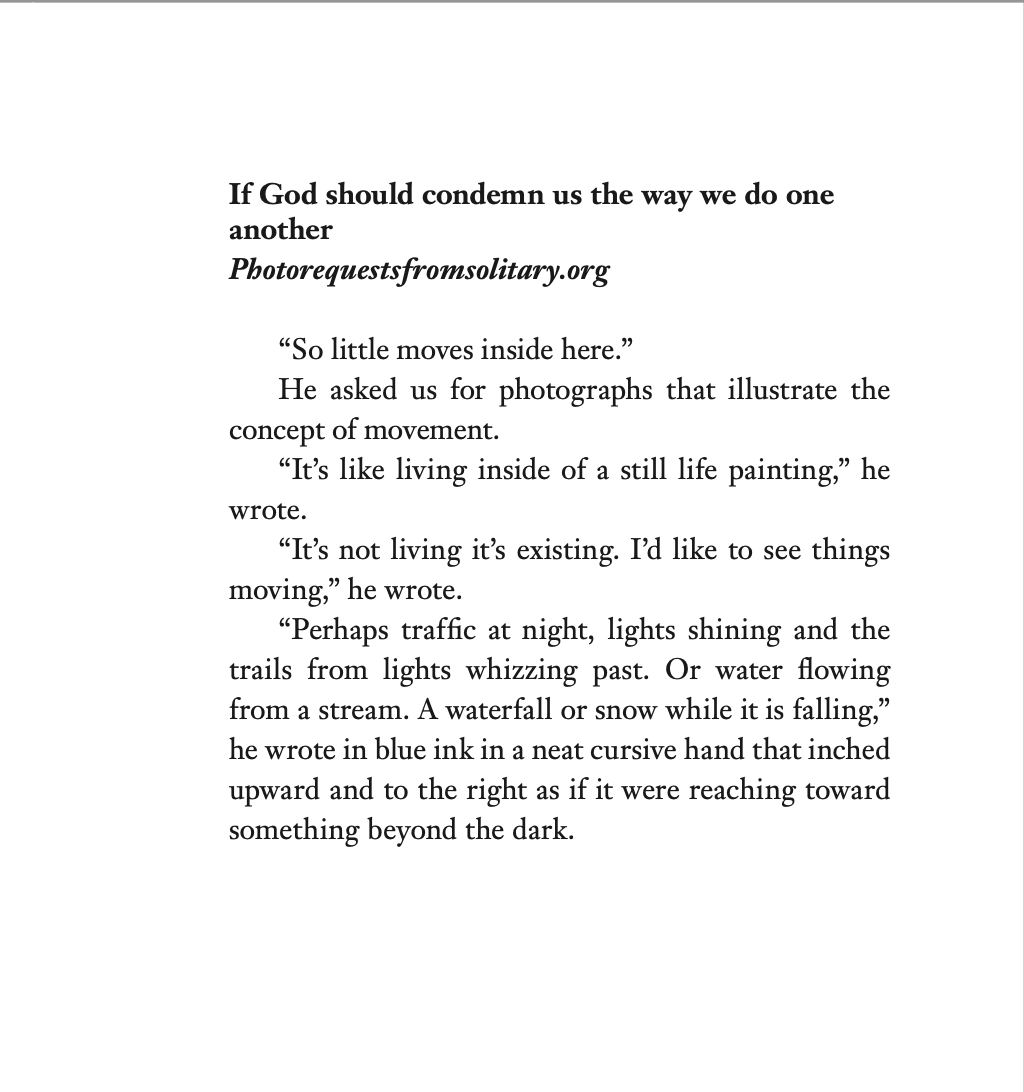

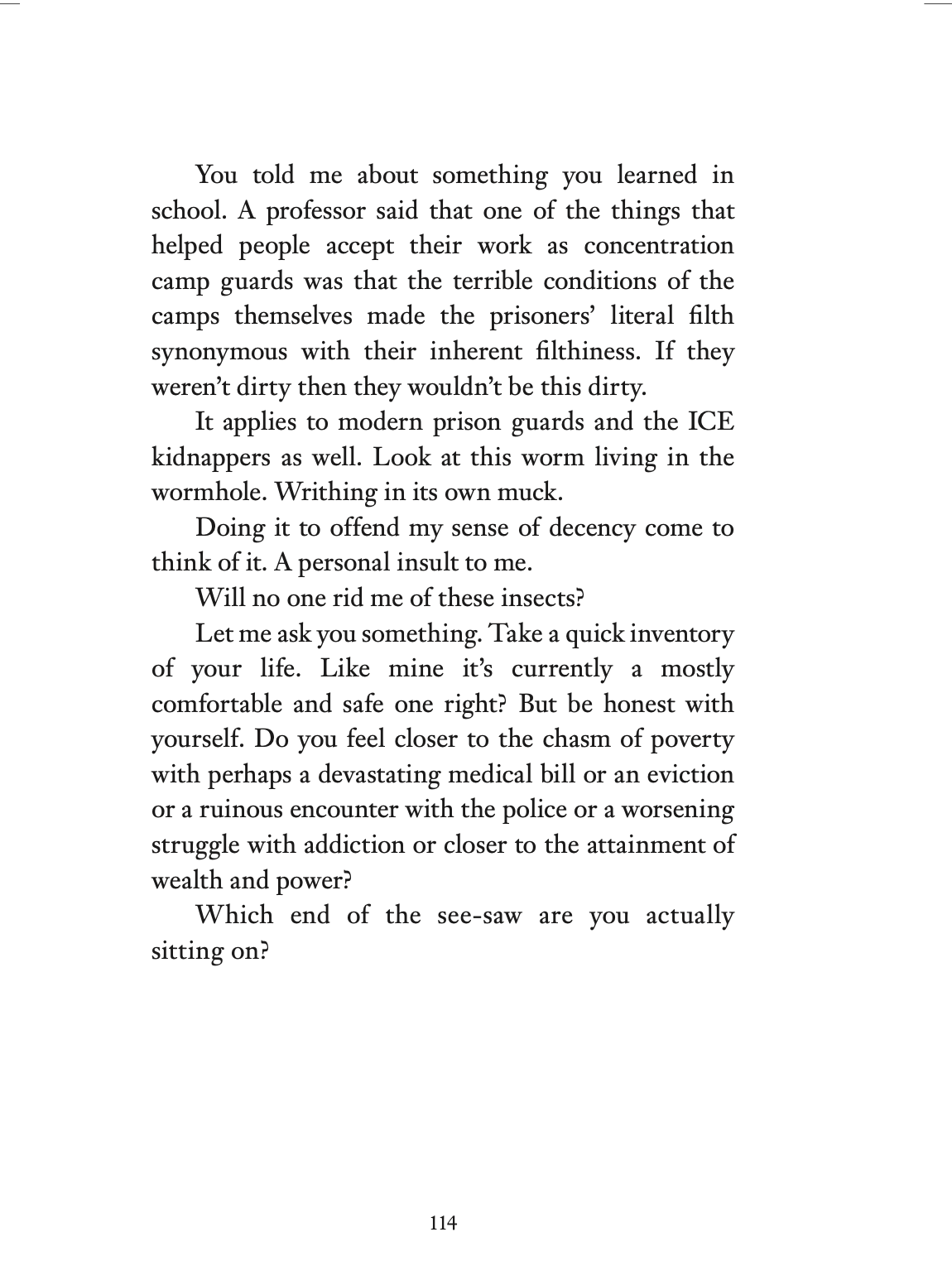

On the horrific torture of solitary confinement.