When will my reflection show who I am inside?

And what if it already does?

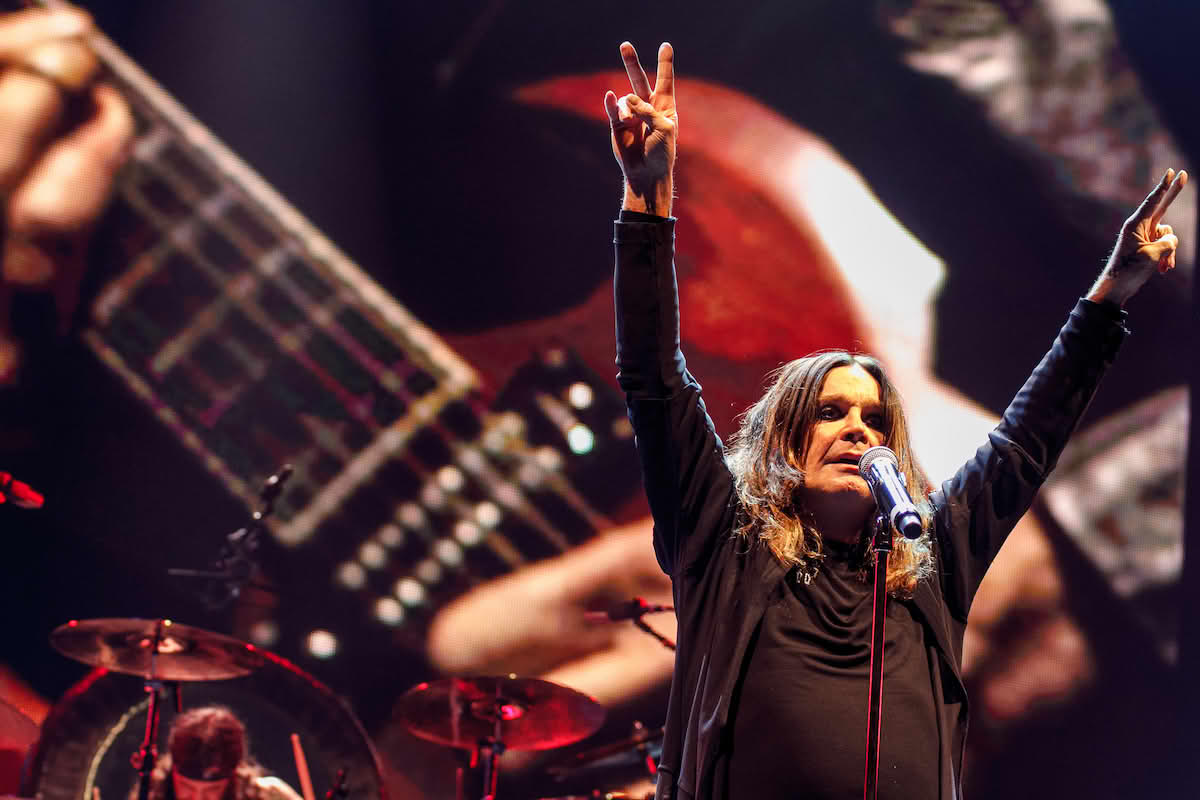

This piece was sent out as part of today's full Hell World newsletter. Read the rest here including a remembrance of the life and work of Ozzy Osbourne.

As you know it costs money to pay for the writing and reporting we do here at Hell World so please consider a subscription if you have the means to do so. Here's 25% off one year.

by Del Winters

Ah, will I gaze on my country’s shores, after long years,

and my poor cottage, its roof thatched with turf,

and gazing at a few ears of corn, see my domain?

An impious soldier will own these well-tilled fields,

a barbarian these crops. See to what war has led

our unlucky citizens: for this we sowed our lands.

– Virgil, Eclogues 1.1

You know when I came to this town after Korea, there was nothin’.

I brought the mall here. I got the 7-Eleven. I got the Fotomat here.

Christ, JCPenney is comin’ here because of me.

– Road House (1989)

Against a backdrop of picturesque old houses in Astoria, Oregon, two brothers comfort each other on the wraparound porch of their home, soon-to-be demolished for a country club. On a horse ranch in Jasper, Missouri, a salt-of-the-earth farmer glares across a canal to the man ruining local businesses with extortion, firebombs, and monster trucks to make way for chain stores and shopping malls. American fears over greed, corporate land grabs, and the disappearing small town way-of-life pop up again and again in 1980s and 1990s movies, from kid favorites like The Goonies (1985) to neon-violent cult classics like Road House (1989).

Degradation of the pastoral life by outsiders and the seizure of private property is not a fear unique to the last two decades of the last millennium of course. The ancient Roman poet Virgil bitched about losing land to soldiers returning home from war in 42 BCE. However, deindustrialization and deregulation in the 1970s and 1980s sharpened those fears to a fever pitch. Who Framed Roger Rabbit steamrolled the box office charts in 1988 by exploiting middle-class white American hand-wringing over eminent domain that mostly harmed working-class Black neighborhoods. By then, we were years into the Reagan administration’s dismantling of the New Deal safety net. In a country with robust participatory democracy, these fears could have been transformed into political leverage. Instead, as happens often in America, anxieties best answered through political organizing were instead only answered at the cinema.

If you're the protagonist of these movies, the person ruining your community is known to you. At your moment of triumph, you can tweak them on the nose or riddle them with bullets or rip up their foreclosure documents because they're there, physically, in front of you. As corporations snapped up more and more land and strip malls emerged as the dominant suburban life form, movies where neighbors and friends came together to save the town occupied less and less of the pop culture milieu. The fight was lost, and by the next decade a new villain had emerged, this time in the mirror.

I've worked in offices before, and they are a particular kind of crazy-making. I could predict the half-life of a break room donut down to the centimeter. I tapped the clacky buttons on the old school keyboard next to the printer just to feel something. I amused myself imagining the politely concerned face my coworkers would make if I suggested unionizing. I never considered punching myself in the face about it, but then again the donuts didn't emasculate me.

The job-induced ennui of the white American man fathered in black comedies like Clerks (1994) and Office Space (1999) and violent fantasies like Falling Down (1993), Fight Club (1999), and American Psycho (2000). After two decades of union busting, corporate layoffs, and cubicle purgatory, men emasculated by at-will employment and emptied out by morally bankrupt jobs were ready to let the intrusive thoughts win. What can you do when your true antagonist is nameless, faceless, and so far up the corporate ladder as to be as ever-present and ever-absent as God? You can't punch Reagan–not without Jodie Foster-induced limerence–so you might as well punch yourself.

The other option is to become a deity yourself, but it’s only available if you’re unknowingly an avatar of gender dysphoria like Neo in The Matrix (1999). Sorry about the self-inflicted bruises, Edward Norton.

Hostile takeovers ravaged Wall Street in the 1980s, emboldened by Reagan’s tax policies. Americans rejected the old consumerism of regulating businesses and embraced the new consumerism of purchasing on credit. American Psycho author Bret Easton Ellis created Patrick Bateman out of his own alienation and isolation triggered by the consumerist void of the time. Sure, the 1980s had movies about immoral suits like Wall Street (1987), but the protagonist redeemed himself at the end. The 1990s even saw Richard Gere and Danny DeVito play corporate raider love interests in Pretty Woman (1990) and Other People’s Money (1991). Only in 2000, when raiding had long fallen out of favor for institutionalized private equity, did the fear of being the corporate raider appear on the silver screen. These films rejected feel-good redemptive endings, embraced violence, and shattered the psyche of the protagonists. This trend might have continued unabated if not for the dot-com crash and the culture-fracturing shock of 9/11.

The post-9/11 landscape and aspirational wealth of y2k settled the question of whether you should really get so upset about your money that you get violent about it. No, it turned out, because making money is patriotic. Americans do love a story about a man torn between his morals and exorbitant amounts of money though. Sometimes these men get whisked off to action-thrillers like James McAvoy in Wanted (2008), which is more or less The Princess Diaries (2001) for desk jockeys, but mostly their anxieties about what to do if someone offers you a dump truck of cash manifest in serious dramas starring George Clooney like Michael Clayton (2007) or The Descendants (2011). Other entries include Thank You for Smoking (2005), 99 Homes (2014) and Promised Land (2014). Gone are the community victories of the 1980s, vanquished is the nihilism of the 1990s, and standing in the wreckage of the subprime mortgage crisis is individualism; the atomization of the suburbs perfectly replicated in the mind of the American man.

The term enshittification, the ratcheting up of customer extortion over time by online platforms owned by capricious billionaires, was coined in 2022. That same year, three fat-cat-and-mouse movies were released: Glass Onion, Triangle of Sadness, and The Menu. If Edward Norton's the Narrator in Fight Club is you as both protagonist and antagonist, then what to make of Edward Norton's Miles Bron, the capricious billionaire antagonist of Glass Onion? Now, we no longer struggle to identify our corporate overlords, because they can’t help but announce themselves. Despite his newfound corporeal form, the villain is more untouchable than ever before. He leverages our desires for dominance and career prospects against our morality, betting that we will continue to buy what he's selling as long as he controls everything.

What are you afraid of? How does the story end? The answer to the first question is difficult to see clearly, and the second is unknowable. We turn to stories to understand ourselves. As more filmmakers from a wider swath of humanity tell their stories, the trends change, they rhyme, and sometimes they converse. The Invitation (2022) preys on class anxieties but also weaves in race and the kind of marital fears found in Get Out (2017) and Ready or Not (2019). In the 1980s, white families fretted about losing private property; in the 2010s and later, Black characters fought against becoming private property through forced marriage or enslavement. Other movies from the 2010s grapple with the housing policy failures and hustle culture created by neoliberalism, such as The Florida Project (2017) and Parasite (2019). Some non-English language films fall outside these decade-long trends, too. Leviathan (2014) and As bestas (2022) are concerned with land disputes and private property, just like American films in earlier decades, although their resolutions don’t repeat the communal victories or morally redemptive antics of the 1980s. Monkey Man (2024) from actor-director Dev Patel is a revenge rampage against a police chief and a Hindu nationalist who killed the main character’s mother and built a factory over the remains of his pastoral childhood home. In the end, Monkey Man rejects going high for the finality of going low.

Small towns decay, corporate suits raid, and oligarchs play. The movies reflect our fears back to us long after the opportunity to prevent our fears from materializing has come and gone. It can be tempting to look at specific movie trends and see a cause-and-effect from box office returns to political outcomes, but the reality is often more complex and context-dependent. Movies are a reaction to outcomes created by political realities of years past, but they can also reinforce individualism over collective action. Stories with main characters tend to do that. The solution to the cult of individualism is not a different type of movie – it’s a different type of politics that prioritizes community-building, organizing, and, yes, media literacy and education. Cool guys with slick hair and sharper jawlines don’t go around kicking the shit out of the JCPenney’s man. In lieu of consequence-delivering cowboys, perhaps we could all organize something in addition to a trip to the movies, like a neighborhood block party, or a workplace, or even a country. Who knows, maybe one day they’ll make a movie about it.

Del K. Winters is a freelance writer who pens essays for MovieJawn and the love of the game. You can find their work at AbsoluteReality.blog. She lives in the best city ever, Philadelphia, with her partner and two-point-five cats.