When I call I need to know you’ll be home

Then I watched Priscilla

I'm very happy to have Rax King back to write about Sofia Coppola's new film Priscilla. Read more from Rax in Hell World on Lana Del Rey's Born to Die, an excerpt from her book Tacky on the band Creed, and her top five Weezer songs.

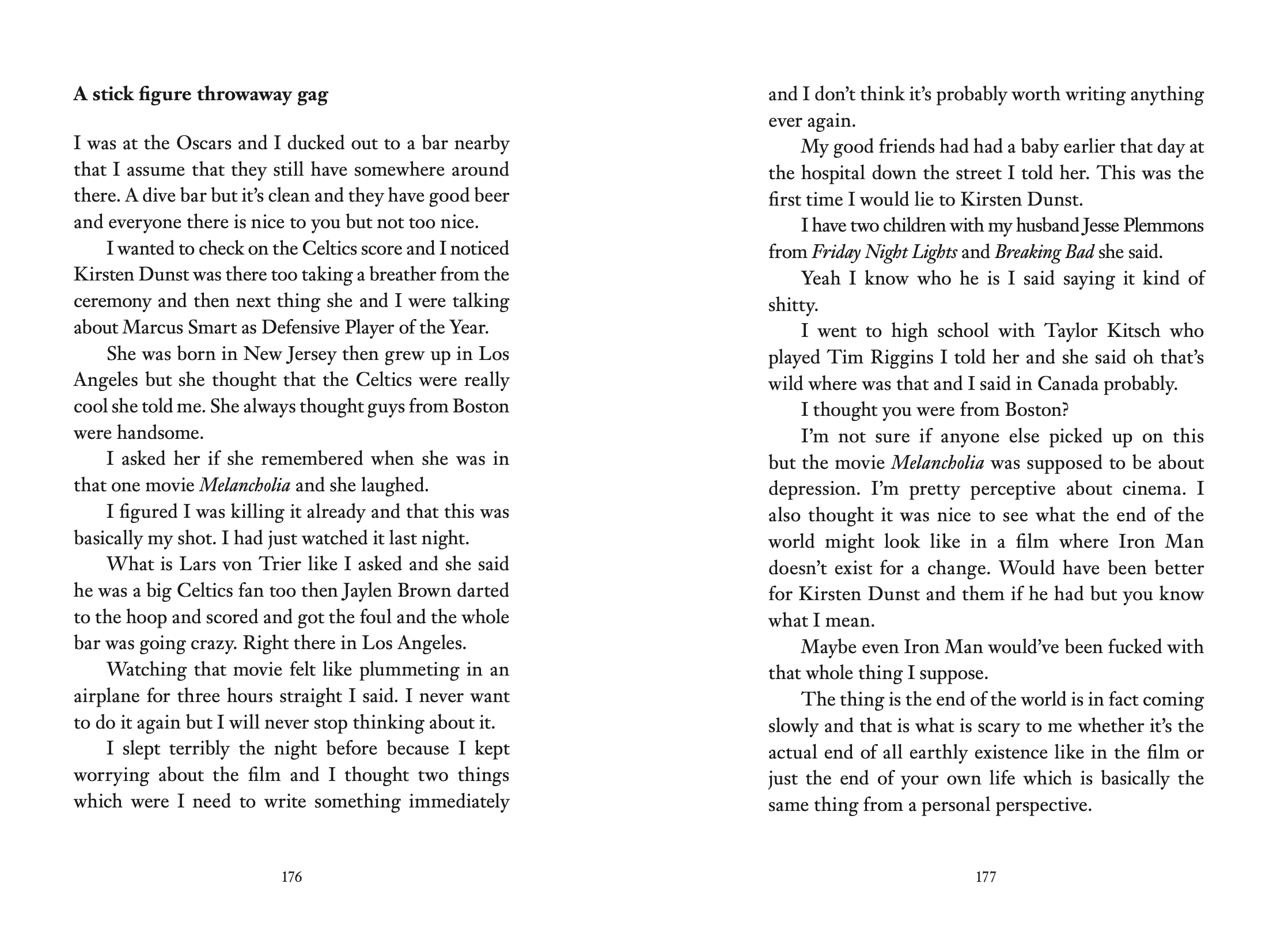

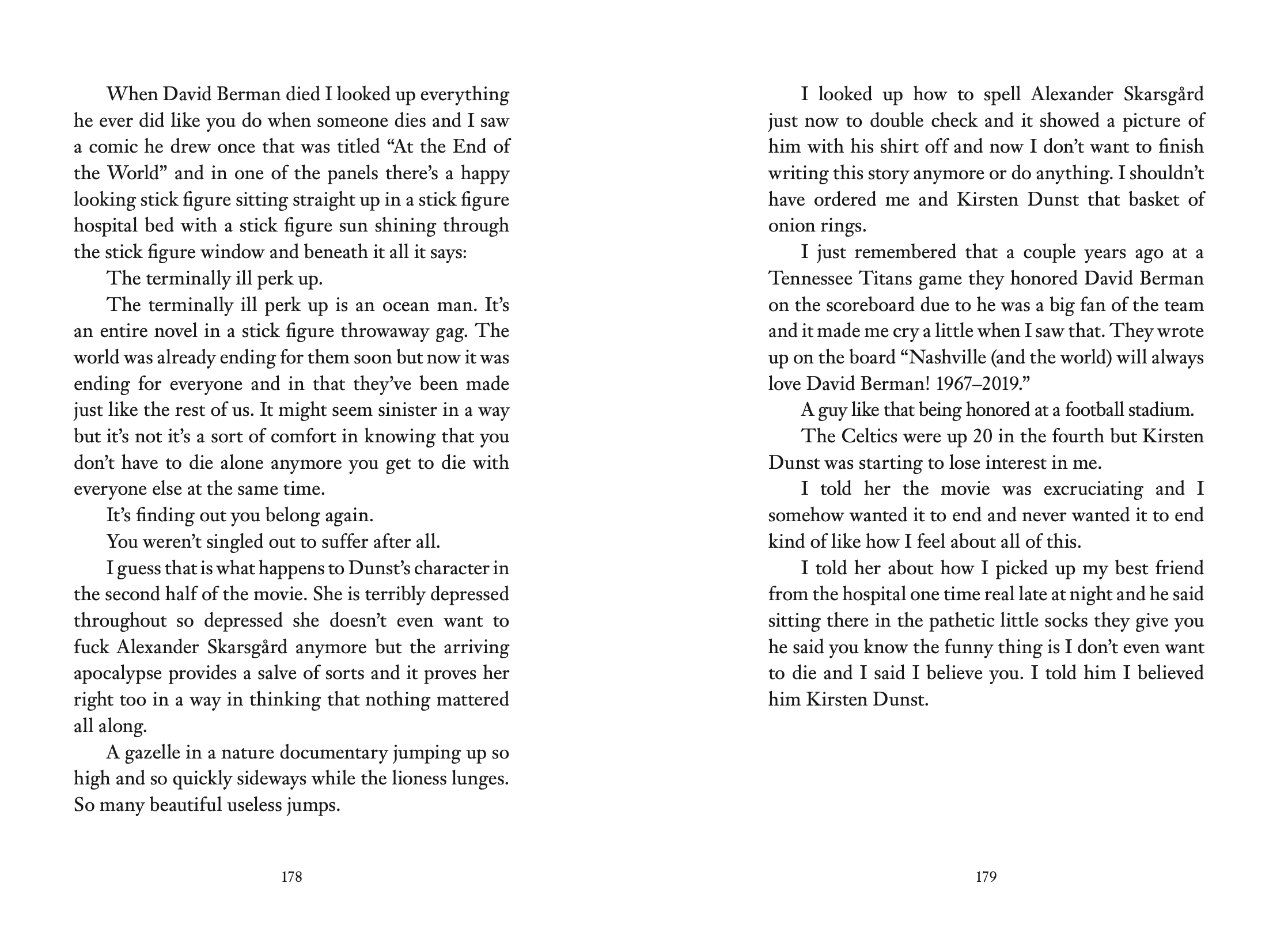

And speaking of Sofia Coppola’s girls you might also read this short story from my recent collection A Creature Wanting Form featuring Kirsten Dunst the singular Sofia Coppola girl.

Please subscribe for free or for a modest sum to help me support my great freelancers like the one we have today.

This Priscilla is all interiority

by Rax King

Sofia Coppola’s girls want, but do not get. Her films are about the muffled-scream agony of young, romantic women trying really hard to want less. They are heterosexual in a way that feels important to point out, because everything Coppola’s girls want, they want from men. They snuff out every desire they have and then wait patiently for the men they love to meet the needs that remain. The men stay put and all that’s left is for Coppola’s girls to compress even tighter. They have about one square foot of life to move around in.

They never seem resentful, Coppola’s girls, which frustrated me for a long time. Their lovers’ casual cruelty causes them pain, but they digest that pain serenely. Why didn’t Lux Lisbon shove Trip Fontaine into a locker for abandoning her on that football field? Why didn’t Marie Antoinette give Louis XVI a swirlie after he spent all those months refusing to even discuss consummating their marriage? It seemed Coppola’s girls could always take more shit, and for years this turned me off. Still I gobbled down her films until they made me sick. I may not have liked them, exactly, but clearly they contained some enzyme I was hungry for.

Then I watched Priscilla, Coppola’s 2023 biopic about the relationship between Priscilla and Elvis Presley, and damned if I didn’t have an epiphany. It happened early on, when a 14-year-old Priscilla Beaulieu (Cailee Spaeny) is sitting on a sofa next to 24-year-old Elvis Presley (Jacob Elordi). The two are leaning into one another without making contact. Electricity crackles between their faces. Then, Elvis touches the tip of Priscilla’s finger with his.

I fell. I plummeted through the foundation of the movie theater, away from my 32-year-old woman’s life, which is as close to my dream life as most people ever get. I landed with a shock in my fifteenth year, when life was even better than my dream life, because nothing had happened yet and that meant anything could happen. And I relived, for the first time in over a decade, that glorious moment when my twenty-something boyfriend’s hand finally, finally traversed the ruthless tundra of distance between us so that our pinkies — and only our pinkies — were touching.

In that moment, I felt an arousal that is no longer in my spectrum of sensations, and I don’t just mean sexual arousal. It’s true that, for my teenage hormones, even the touch of a pinky could keep me horned up for weeks. But while being touched by that grown man, as every trustworthy adult voice I’d ever known screamed in my head that he shouldn’t touch me, what I felt was triumph. I trusted adults generally; I believed no adult man would cross those boundaries with me unless I was really, truly special. Priscilla is a film about what life is like for the girl who doesn’t place that trust in an ordinary man, but in a King. How naive we both were, and how easy to prey on!

After young Priscilla Beaulieu’s first visit to one of Elvis’ parties while he’s stationed in Germany, her parents try (feebly, I might add) to bar her from seeing him again. Her response isn’t that she loves him or that he’s important to her. Instead, she mumbles “there’s nothing to do here” and storms out of the room. Priscilla has long suffered from the same suspicion that plagues well-behaved girls everywhere, which is that the whole world is having fun at a glamorous party you alone weren’t invited to. Elvis literalizes this for her, welcoming her into a world that is itself one big glamorous party, where the music never stops and there’s a drug to induce every mood you could possibly want to have. He leaves Germany, and she can’t think about anything but him — because she misses him, sure, but also because he took the keys to the party when he left.

That’s the thing about the sorts of older men who “date” teenagers. Their power comes from the fact that they, and not we, are hosting the party. They buy the beer and their parents are never home to interfere. We push our childhood away with both hands and they snatch it from us, greedy for our youth. It’s an ugly symbiosis. They tell us we’re mature for fourteen or fifteen, and because we’re fourteen or fifteen we believe they’re saying something real about us, not something wistful and shameful about themselves. There’s a reason this behavior is so common among rock stars, who are made childlike and stunted by the fact that so few people are willing to tell them No.

Elvis takes Priscilla to play bumper cars all day and shoot off fireworks all night. He gives her drugs she can’t handle and then shepherds her through their effects in a wise-old-druggie persona that I found cringe-inducingly familiar. His cronies, the Memphis Mafia, are always there and always grab-assing — Coppola has a real knack for showing boys at play, whether they’re jumping over each other’s bodies on roller skates or throwing each other into the pool. Priscilla spends her adolescence in a frat party environment that I’m sure felt perfectly natural. It is, after all, an environment that rightly belongs much more to her than to her thirty-year-old lover and his friends.

Priscilla hungers for Elvis physically as only teenagers can hunger. But he won’t have sex with her. He fetishizes her “flower” as well as his own piousness about preserving it. In Priscilla Presley’s memoir Elvis and Me, from which much of Coppola’s film was drawn, the author explains that this abstinence pertained only to her literal hymen, that she regularly “pleased” Elvis in “other ways.” As such, it’s hard to see Elvis’ refusal to have sex with Priscilla as anything but another method of keeping her in his thrall. Yes, it’s unequivocally wrong for adults to have sex with teenagers, but he was already doing exactly that in every sense but the most dementedly literal. The most meaningfully different thing about the one act where Elvis drew the line was that it might have given her a little relief. Strain a girl to her absolute limits with wanting you, and she won’t have any space in her life for wanting anything else.

That seems to have been important to Elvis — that his girl could want nobody and nothing but him. In one scene, Elvis is away filming one of his musicals; Priscilla is sitting in Graceland alone waiting for him to call, which she spends much of the movie doing. This time, at least, he does call. She mentions how bored and lonely she is with him away, and that a local boutique has offered her a part time job.

“You’ll have to let that go,” he says, his tone patient. “When I call, I need to know you’ll be home.”

Priscilla gets the message. From then on, she only comes alive when they’re together, and visibly powers down when he’s saying goodbye before another tour or film shoot. Even when the two live together, even well into their marriage, the original dynamic never changes. He’s hosting the party, and she’s a guest. In her own house, in her own life, she’s a guest.

Some critics have described Coppola’s Priscilla as lacking interiority, but to my mind, the opposite is true. This Priscilla is all interiority. She wants to be dug into. She wants to be found. Like many of Coppola’s girls, she says little, but her desire to be seen is written all over her face, especially as time goes on and her husband sees her less and less. Watch her work up the nerve to tell Elvis she can’t take it anymore, and then watch her settle into immediate resignation every time he calls her bluff. They both know she can and will take more.

Because he’s the only person who ever tried, however shallowly, to dig into her, Priscilla takes a lot from Elvis. She pretends to believe him when he swears he isn’t having affairs with his co-stars; she says nothing when weeks go by without a call from him. She willingly enters a love deficit, her heart eating itself like a malnourished body does. What keeps her going is her belief that he must notice her resilience and self-sacrifice, that she’s building up a store of good will she can draw from when she needs something from him. But every time she begs him for something he doesn’t give her, she’s forced to confront the reality: he doesn’t notice how hard she works to obey him. He doesn’t notice her at all.

It’s not a triumphant moment when she leaves her husband for good. In that moment, she becomes one of Coppola’s girls, wanting but not getting, for isn’t Elvis the only thing she’s ever truly wanted? Now she will never have it, and must accept that she never really did.

Do those years of self-effacement weigh on her? Does she ever feel bitter or resentful?

The only answer we, the general public, are likely to get to those questions is… nope! Since Elvis died, Priscilla Presley has fashioned herself as the keeper of his legacy, and she tends to make their relationship sound like a fairy tale: the mousy girl getting swept off her feet by a King from a faraway land. Some ascribe cynical motives to her, pointing out that she’s made her fortune in the Elvis industry and wants to tell a commercially friendly story. Maybe that’s true, but I’d wager that there really is a touch of fairy tale in the way she remembers Elvis, if only because their relationship ended on such an unsatisfying note that she probably still feels they have unfinished business.

Onscreen, Coppola renders, with her usual loving precision, a girl’s dissatisfaction. Priscilla rubs against her husband, kissing his earlobe. He doesn’t even put his book down. For days, she builds the courage to ask him if she can visit him on set, days she realizes were wasted when he gives her nothing but a careless no. She learns to abort her expectations. She wants, and doesn’t get; she learns to want less, and doesn’t even get less. It might be Coppola’s best film. In it, she gives her girl nothing — beautiful clothes, jewelry, cars, drugs, nothing.

Rax King is the James Beard award-nominated author of Tacky (Vintage 2021) and Sloppy (forthcoming from Vintage). She lives in Brooklyn with her toothless Pekingese.

For more film writing on Hell World please see Donald Borenstein on Stop Making Sense.

Or Vince Mancini on the Cheetos movie.

Or both me and Vince talking about The Menu.

I've been reading a collection of Raymond Carver's poetry lately so fuck it here's a Raymond Carver poem for you to read and enjoy.

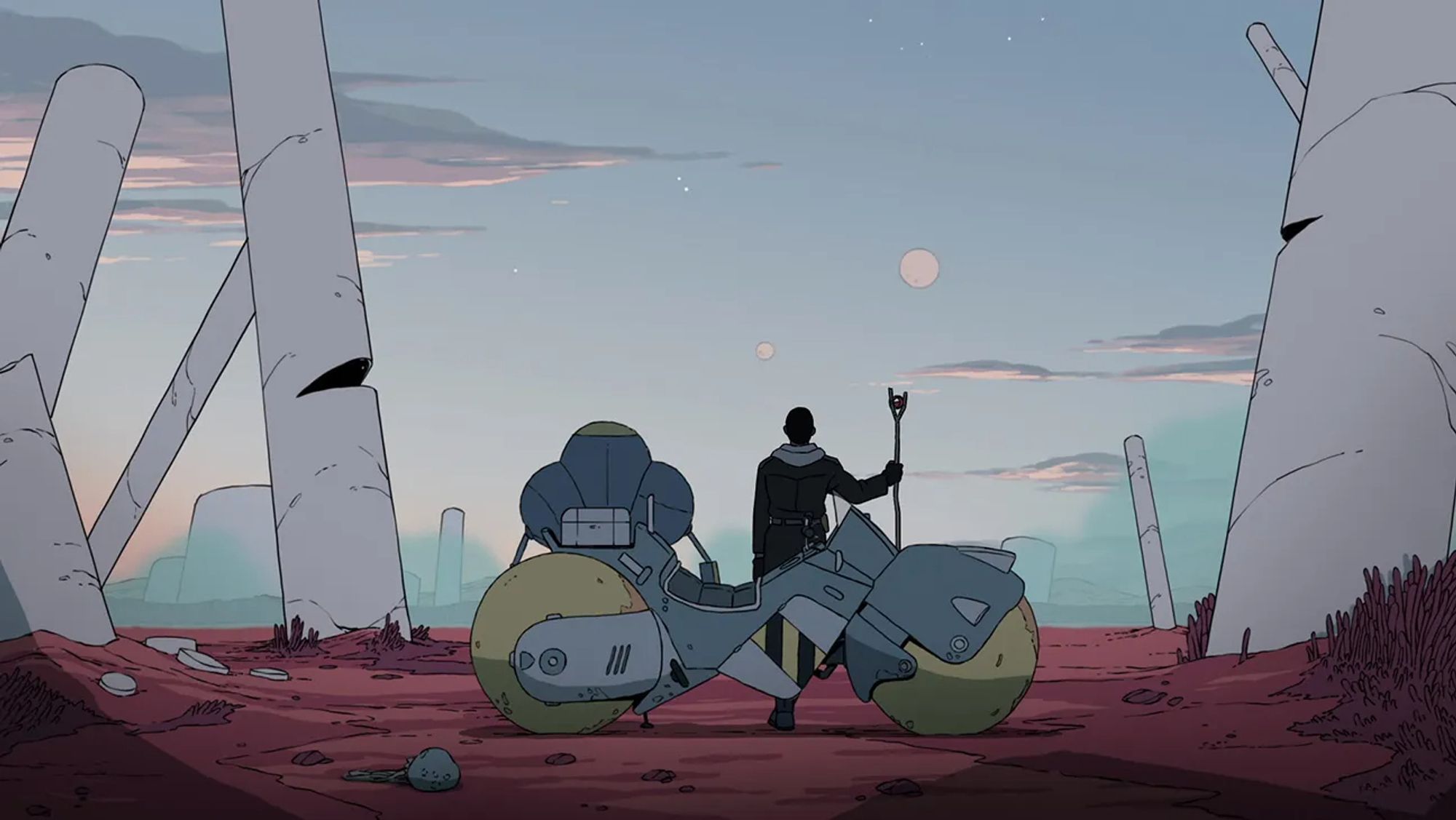

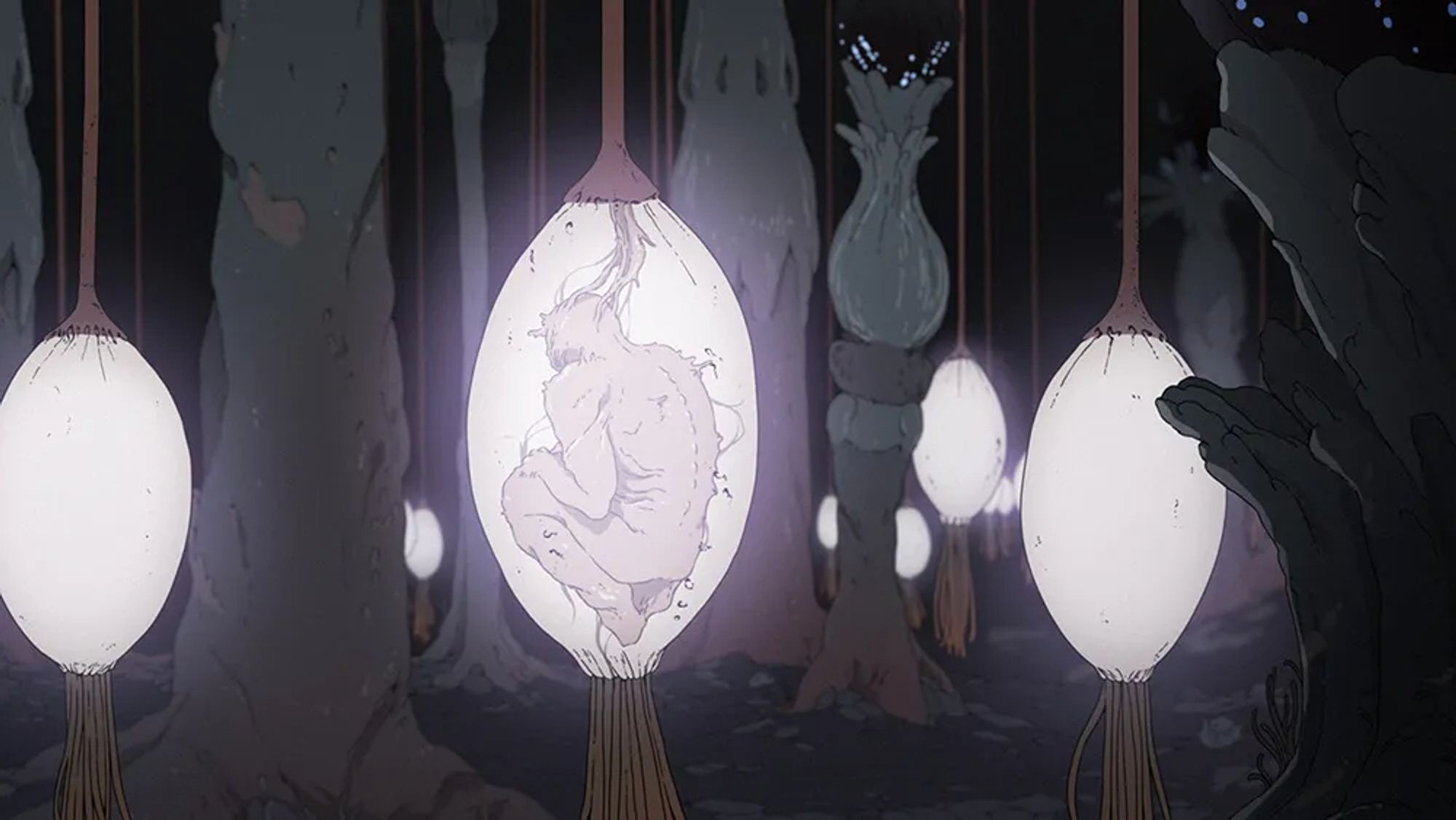

Also please check out Scavengers Reign on HBO. Some great cosmic horror/ body horror.