A million ways to get things done

Donald Borenstein on Stop Making Sense

Today a brief respite from the horrible with a great piece about watching Stop Making Sense and Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour. Well not brief that is a lie. It's very long but you know what I mean.

"The world is getting smaller as it gets bigger, the crises multiplying in a way that makes the lyrics of 'Life During Wartime' feel increasingly vivid," Donald Borenstein writes.

"I think that’s crucial to why this re-release of Stop Making Sense is having such a moment, and it’s not simply because of nostalgia. I think there is a striking realization that something like it just might not happen again: the perfect confluence of a band in its prime, a filmmaker with a vision, and even a modest blank check from a studio."

Thanks as always for reading. Help support our writers with a subscription if you can.

A million ways to get things done

by Donald Borenstein

For a brief, shining moment, the concert film was not merely a promotional exercise in exhaustion, but a treasured form of mass pop culture. As one of the only forms of documentary filmmaking that the broader public engaged with regularly, concert films were both a proving ground for young filmmakers and a chance to flex creative muscles for some of the most respected talents of their era.

Shepherded by trailblazing works like Monterey Pop, Gimme Shelter, and The Last Waltz, the medium arguably reached its peak in the 1980s as musicians themselves took on a greater creative role in the films. Musicians like Prince brought a singular sense of both musical and visual authorship along with trusted collaborators behind the camera, and the rise of MTV proved a massively profitable market existed for a non-stop stream of these works.

This, of course, was too lucrative to stay the case, and rose-colored glasses might help us forget about how many films of the era were also just cynical branding gimmicks, from phoned-in stadium spectacles to noxious and impotent standup specials, both mainstays of the medium to this day.

So why do people still fixate on the potential of a medium with such poor creative returns? There are a lot of longer answers you can give, but the short answer is Stop Making Sense. Jonathan Demme’s landmark concert film documents Talking Heads’ last full tour, painstakingly filmed over three performances in Los Angeles’ Pantages theater and cobbled together into a cohesive whole. Stop Making Sense was a modestly profitable cult hit that became a cultural icon over time by a band that was, for most of its career, a modestly profitable cult hit that became cultural icons over time. An odd origin story for what is now indisputably the most acclaimed concert film in history.

But it’s hard to not feel a little bitter these days when looking backwards; to be reminded of how it has gotten so much harder for even the exceptions to cheat the system. So when I got an email about a screening of Stop Making Sense at the Angelika Village East with a David Byrne Q&A after, it was hard to muster enthusiasm even for one of my favorite films. Would I feel joy at revisiting a movie I’ve seen a dozen times for $20 in a moment when my bank account had $80 in it? Would the immaculate craft of Demme’s canonical performance film simply remind me of the fact that the only concert films we get now look so endlessly sterile with their hyperactive editing?

A large part of my initial cynicism came from the way this moment seemed to be packaged: A24 presents Stop Making Sense, digitally remastered and fresh off an IMAX run as a Special Theatrical Experience(TM). An improbable reunion of a band with an extremely fraught dissolution for a massive film-festival Q&A, a massive rollout of the film as a nationwide buzzy event. It was all the exact kind of fanfare this film deserved, something so improbable and unmistakably good on paper as to arouse my suspicion.

After all, how could it exist in today’s film market? It came from an era when such an entity was possible, even if it was exceedingly rare then as well. The performance films and videos all seemed to stem from the vision behind an album itself, rather than the Artist as A Brand. David Byrne noted at the Q&A I attended after the screening that “In those days it was different from the way it is now, the album was how you made money and the touring [was] how you got people to buy the album.”

The crowd filtered in from a line that wrapped around the corner for the sold-out show, and I was struck by the wide spectrum of the audience, seemingly almost equally distributed across every Neilsen demographic. I sat for a moment and thought about the fetishistic question that comes with every remaster, the one that comes with the parasocial question of ownership every obsessive has: did they fuck it up? Are they all going to look smooth and clean? The kind of needless anxiety that comes with a functional hostility to joy.

This is well-trod emotional territory for any Talking Heads fan, and for Byrne himself. In the Q&A, Byrne spoke about the film as a document of his emotional and creative development with the band. “The journey of this film and this show kind of reflects that... one person who's very intent and focused and serious about what he’s doing, and then gradually in the course of the film, in the course of this show, you see this person kind of let go and surrender to the music.”

Before that the house was packed and the trailers were running. The dissonance was acute – even in the semi-art house Angelika, nearly every trailer used a bombastic, moody, royalties-evading cover of an iconic pop song. Looking backwards, regurgitating, reminding me of the faint taste of something interesting in a way that precluded engaging with this work on its own terms.

The one exception was an extremely notable one: a trailer for the highest-profile concert film since Justin Beiber’s record-setting Never Say Never, a nearly three-hour film documenting international pop superstar Taylor Swift’s career-retrospective Eras Tour. As an artist, Taylor Swift always eluded me. I did not so much dislike her as fail to understand her. There was clearly something there and it was me, I was the problem. The trailer was simultaneously off putting and arresting – it looked relentlessly generic, but with an unmistakable sense of scale that one could not help but admire a bit. It stuck with me in the back of my head as I settled in for Stop Making Sense.

As the Dr. Strangelove-inspired title cards appeared on screen, etched by the same artist, Pablo Ferro, the theater audience roared to life. The silence of the film’s opening was drowned out by thunderous applause and cheers at every credit on screen by the theater audience. By the time the cheers of the Pantages crowd slowly bled into the mix, they were completely drowned out by the audience nearly forty years later in the East Village.

Whatever moronic fears I had about the film being “ruined” by the meddling of restoration were dispelled immediately, as soon as the drum machine tape on Byrne’s boombox came in on his solo acoustic rendition of “Psycho Killer” to open the show. Having watched this film countless times on mediums ranging from worn VHS tapes to terrible torrents to the previous blu-ray version, it has never looked or sounded better. The film has been cleaned up in a way that allows its organic feel to still thrive, but just nudged in a way that clearly matches the original intentions of the film. The inky black shadows from the hard stage lighting are punchier, the sweat beads on Byrne’s face are crisper, the sound is larger than ever and given just enough of a bump in reverb to immediately transport you to the Pantages.

Sonically, Stop Making Sense was already one of the best mixes of any commercially released live album, but in a proper theater there are elements of the songs that never really came out before. The early acoustic numbers are particularly striking for this. On “Heaven,” a personal favorite, the sound of the simple guitar and bass interplay is more organic and dreamlike than ever. Combined with Demme’s endless, drawn-out dissolves between Byrne and bassist Tina Weymouth it creates an ethereal feel, but one that is intentionally punctured by the reveal of a growing set and band assembling behind them in real time.

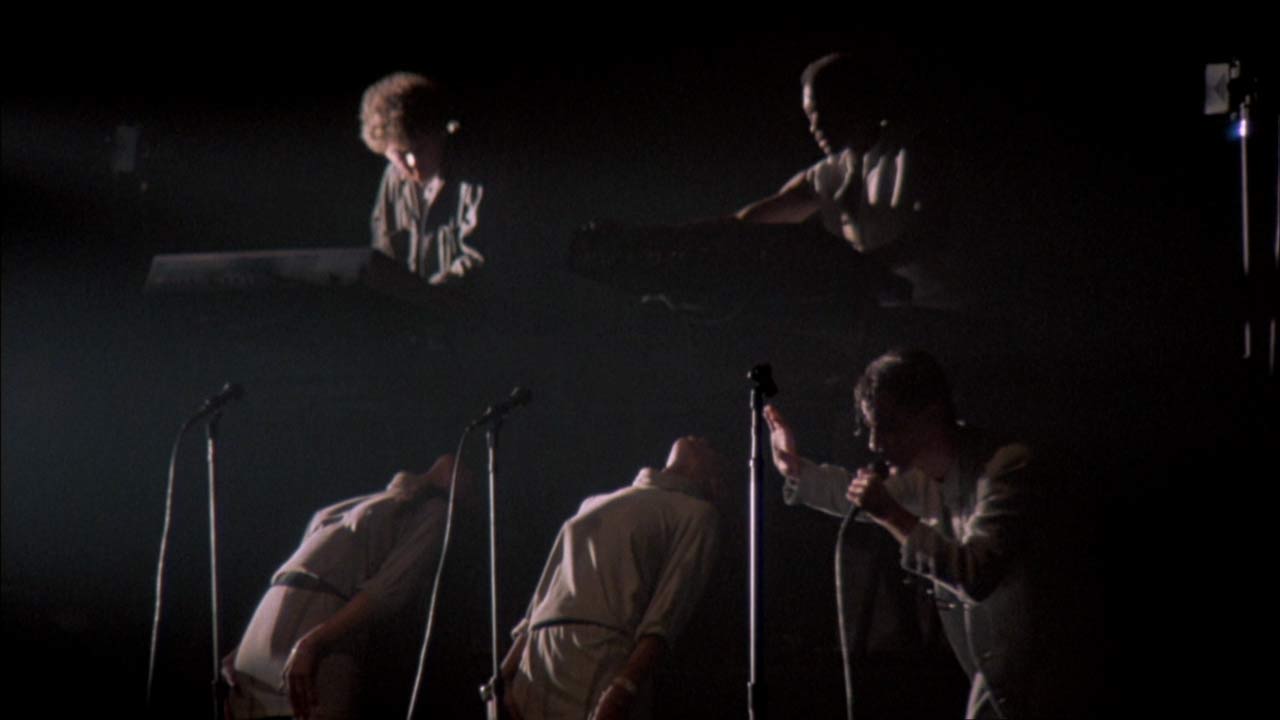

The film’s structure is very conspicuously intended to present the evolution of Talking Heads as an artistic project, the development from Byrne alone on stage, to each member of the original core quartet joining the stage individually on the first four songs. All the while, you very rarely break from this omnipotent viewpoint: aside from always returning to a default, theatrical symmetrical wide shot in each song at some point, the visual language of the film is mostly committed to adapting on a song-by-song basis, punching in individually at a series of angles that feels impossible in a pre-digital age, seamlessly shifting from handheld shots to absurd crane zooms. But notably, Demme almost never cuts away from the band.

This is one of Stop Making Sense’s greatest creative coups, in a move rarely fully imitated by its successors in spite of the massive influence: the audience is a largely unseen, unheard presence in the film. There’s a full house on every night of the show, but they’re drowned in shadow most of the film save for a few brief shots, the majority of them towards the end of the film. Except for brief pauses between a few songs, their cheers are mixed down or faded out entirely. The primary way you see the audience is in wide shots of the full band, silhouetted heads bobbing just the same way you’d see them from your seat.

The performance itself feels mildly Brechtian, or at the very least like an earned abuse of the term – sparse in structure, happy to draw attention to its seams. Everyone is lit with hard theatrical lighting, blocked evenly across the stage like an ensemble chorus with dancing room more so than a band, backed with (mostly) minimal sets evoking a black-box theater. The production crew itself gets notable camera time, rolling out drum kits and bringing out props. One thing the restoration makes clear is that in some shots they do misfocus on David Byrne a little bit, and the film is better for it, portraying him as a force of energy whose location and velocity cannot simultaneously be pinned down.

Between this and the decision to eschew interludes, interviews, banter, or any kind of filler whatsoever, Stop Making Sense trusts that the show it’s sharing with you is immersive enough to make you feel like you’re there. About half an hour in, Byrne almost taunts the moviegoing audience by asking “Does anyone have any questions?” before immediately cutting to the next song. There are no audience shots to reinforce your sense of participation, interviews to develop an unearned feeling of intimacy, behind the scenes moments to remind you they’re just like us. Stop Making Sense has no time for this. It’s all gas, start to finish. By the time the nine-piece band arrived on stage for “Slippery People,” parts of my theater were already dancing in their seats.

It’s no surprise this was the moment people started to get into it. “Slippery People” is the point where Stop Making Sense blows the roof off the place, a transcendent escalation via one of the single greatest live performances ever committed to film, a raucous and bouncy party jam where we get to revel in the joyous energy each member of the ensemble brings to the table. Demme and legendary cinematographer Jordan Cronenworth stick largely on two long, drawn out bouncing handheld medium shots, and the result somehow manages to capture the feeling of staring up from the pit, but with an intimacy that you could never possibly get from your seat in row 2 or 22.

By the back end of the song, after a number of joyful introductory closeups on brilliant percussionist Steve Scales, vocalists Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt, guitarist Alex Weir, and Parliament/Funkadelic legend Bernie Worrrell, we’ve cut back to the wide, half the frame shrouded in darkness where the audience should be, showing the stage as one gigantic dance party.

No single track rose in my esteem in the remaster more than “What a Day That Was,” a repurposed track from Byrne’s phenomenal solo LP The Catherine Wheel. The performers are all bathed in underslung hard narrow lights that keep them each on the verge of near total inky blackness, like they’re singing by candlelight. Demme and Cronenworth use almost entirely tight individual shots here, all of them tilted at least a little bit upwards, cutting only briefly to a wide at points that show the entire band as two-story shadows against a dim gray background. All of this is intercut with quite possibly the most anxious and manic song Byrne has ever written. It’s a truly transcendent performance that, with the restoration, looks impossibly beautiful.

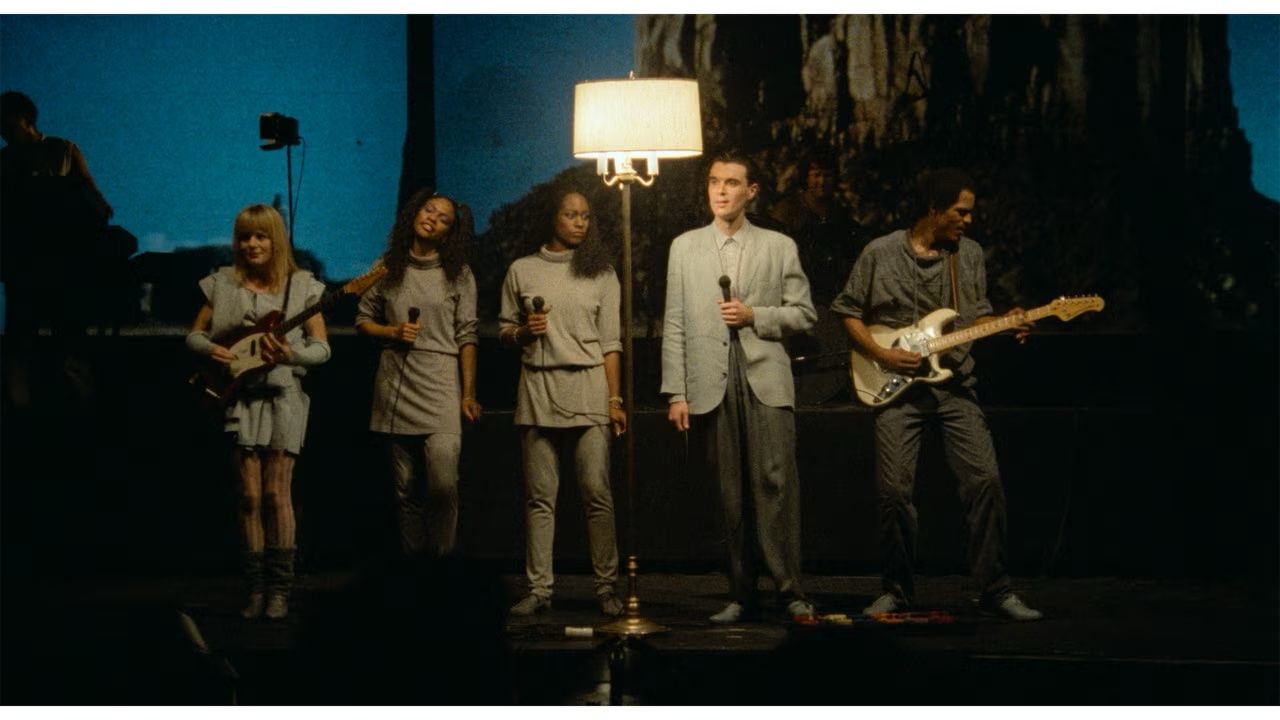

When people talk about the uniquely filmic feel of Stop Making Sense, what they’re talking about, consciously or not, is the way this film uses light better than any filmed musical performance in human history. It creates a beautiful subconscious narrative flow between the tracks in a way that no interlude and no behind the scenes moment ever could. This is best felt in the transition between “What a Day That Was” and one of the greatest love songs ever written, “This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody).” The hard, infinite shadows give way to Byrne bathed in a single lamppost, a soft, dim, warm light that eventually starts to spread to the entire stage as he begins his iconic dance with the lamppost. It is an unmistakable shift in the mood. The anxiety never leaves the band’s sound – what is a Talking Heads song without it? – but the setlist for the remainder of the show feels and looks unmistakably looser from here.

This brings us to what might be the most inexplicably controversial moment of the film, the brief moment Weymouth and drummer Chris Frantz are given the spotlight for their classic Tom Tom Club single, “Genius of Love.” A small chunk of the movie theater audience foolishly got up for the bathroom here, forgetting that the song also functioned as a very important costume change for Byrne. They missed out as well: while the performance might not quite capture the brilliant, minimalist energy of a nearly perfect dance track, the angelic chorus of Weymouth, Mabry, and Holt combined with Frantz’s beautifully corny call-and-response hype work is one of the most joyous moments of the entire film.

When Byrne returned for the final run of the set, in his iconic massive suit for “Girlfriend is Better,” nearly half the audience in the theater got up to dance and never sat back down. The energy was infectious, but my seat was smack in the middle of the theater, and so I didn’t get up. I thought back to a spare moment in the film where you briefly saw the audience in a vaguely perceptible light, and noticed that there was the kind of mix of dancing and muted indie-rock bobbing you’d find at any show of this type. I recognized myself firmly in the latter and thought about what it would feel like to see yourself, even briefly and out of focus, not dancing during one of the most energetic and legendary live performances in the history of pop music, captured in celluloid for time immemorial as low-energy?

It’s hard to really find a comparison point for this level of audience participation and reshaping of a film short of a Rocky Horror or The Room screening. The entire audience just surrendered to the idea that they were not watching a movie but an actual concert. I’m not sure you can offer a bigger endorsement of the film’s restraint and focus in what parts of a concert it shares. Notably, it is not until the very end here, during the tail end of “Crosseyed and Painless,” that we get to see fully perceptible shots of audience members. You’re here, you’re with them, and you always were.

Fittingly, Byrne noted during the Q&A, that not only was the Angelika Village East theater once a performance venue, but Talking Heads performed in that very space in 1979. Known at the time as the Entermedia theater, the nearly 100 year old building has shifted identities and names countless times in its history, bouncing from Yiddish art and theater venue, to music venue, to movie theater and back again repeatedly. I’m reminded of an iconic line from a later Talking Heads song, “Nothing But Flowers.” “This was a Pizza Hut/now it’s all covered in daisies.” It’s hard to tell what point in that process “Art House theater that mostly shows big releases” is, but stepping outside the building you’ll mostly find Pizza Huts in spirit.

Aside from the moments I mentioned, the Q&A with Byrne was a bit of a letdown. Conducted by someone from A24, the questions stayed safe and broad, with the total absence of any awkward questions that come with the band’s fraught and lasting dissolution and sudden detente. It’s hard to look at Stop Making Sense in absence of that factor. Byrne spent years threatening to leave the band before actually doing so after Naked, and then as recently as 2004 told Weymouth, Frantz and Harrison that he wouldn’t ever reunite under any circumstances. Byrne has, in other interviews, very vocally made contrition for how he handled the breakup, and has gone on a long personal journey this past decade with his own sense of self, so this is not to pile on him.

But this tension is central to Stop Making Sense – as much as Demme’s film is committed to showcasing the band in piecemeal as well as the whole, the live show itself that it captured did not feature these close-ups, these moments in the spotlight. The live show it captured was, functionally speaking, The David Byrne show, at times with him as the only member of the band truly visible, the entire stage assembling around his creative vision. It is a dynamic that is part of why the performance feels so alive, but it’s one that in press comments the band seems committed to revising.

It’s also a fascinating thing to consider in the lens of the modern pop star. There is a way we talk about “the good old days” of music and performance and the artistic titans of yesteryear that sands off these edges, that forgets about the inescapable ego of performance at any level. Watching the Q&A, I was struck by how Byrne exerts a firm sense of control over his public image that is certainly comparable to the widely admired control stars like Beyonce and Taylor Swift have over their own public perception, almost as part of the performance. Byrne is usually presented as a bit of a narrator type, a quirky guide always in the center of the frame who is simultaneously a ball of anxiety but also in moments of peril never gets more worked up than an “uh-oh!” The truth and the lie blur, but it exists as part of a performance so it is not only acceptable but admirable.

On the way out of the theater my immediately jumped back to the previews. Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour appeared to be a highly staged career retrospective performance by an artist with a strong visual command over her work and her public image, blending the two into a single entity that was inseparable from branding itself. But while I knew this about her, and have involuntarily heard her music arguably more than music by bands who I have sought out to see in concert, I know very little about Swift, and about her music besides hearing it passively.

Taylor Swift is an artist whose appeal has historically eluded me, especially in its universality. I don’t dislike her by any means – in fact, I’ve enjoyed a number of her songs, and (in typical contrarian fashion), really liked Reputation. But she was also putting out one of the biggest concert films ever released – now with the largest opening for one in history – that featured a highly constructed and choreographed stage show, recorded over three different nights in LA. Critically, though, The Eras Tour seemed crafted from top to bottom to evoke the exact kind of audience energy seen at this Stop Making Sense screening, a participatory event across the country, for arguably the biggest pop star in the world.

In the days leading up to the premiere 10 pm IMAX showing at Lincoln Square, my friend the writer Rachel Millman – who in her words is “grotesquely obsessed with the fans” – provided me with some extremely vital background research for this piece. That often came in the form of countless TikToks of Overly Enthusiastic Fans trying to dissect the hidden imagery in the leadup to the Eras tour film release. It felt like watching video after video of Charlie Kelly in front of the corkboard, assembling a conspiracy that wasn’t there. Rachel and my partner Lauren would both accompany me to this screening, the former to advise me on the complex lore of the Swift Cinematic Universe, the latter to provide emotional support during this endurance test.

Approaching the AMC, a steady stream of superfans were walking in the same direction, throwing the “don’t wear band merch to the show” rule out the window, as they should. But strikingly, for the first IMAX screening of the film in the biggest theater screen in New York, there wasn’t a full house. Blame the Thursday 10pm time slot, I suppose. The audience more than made up for it with enthusiasm: it’s the first time I’ve ever seen anyone bring glow sticks into a movie theater.

I knew we were in for a somewhat surreal experience as soon as the trailers started rolling, with nearly every movie featuring a Swift needle-drop. This was a theatrical experience put on rails by the most skilled PR team in the world, an immaculately curated Tumblr feed with an international IMAX release, a parasocial breadcrumb trail.

When the film kicked off with some of the most massive drone shots of a stadium I’d ever seen, combined with the roar of audience cheers mixed like Oppenheimer, I initially regretted my decision to oblige myself to three hours of this. However, in a refreshing surprise, Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour does not overly indulge in the audience shot for the most part; it certainly cuts to the audience in wide almost constantly, but then again it cuts to almost every possible angle constantly so those shots at least never overstay their welcome.

Eras the film – directed by modern live-show veteran Sam Wrench, whose work includes previous concert docs for Billie Eilish, Blur, Mumford and Sons, and Pentatonix – more often than not feels sterile and inattentive, unable to stick to its guns at any point, unsure of where it wants to look, unsure if you’re still paying attention at all unless it constantly pivots around to try and convey an endless sense of scale.

It’s a shame because the craft on display for Eras as a live performance itself is so remarkable as to make me wish I got tickets to the actual concert. With incredibly detailed and ornate stage sets for every single number, Eras takes the opposite approach of Stop Making Sense by going for absolute maximalism, and remarkably at its best moments achieves a comparable effect. Swift’s songwriting is constantly refracted and reflected through images of herself, as best exemplified through her music videos, which manage to still gain cultural traction in an era where music videos have often become delegated to an afterthought.

Eras follows the same structure as the tour itself, albeit with songs cut for “brevity,” featuring at least one song from each of her ten studio albums, not in chronological order. Opening with her slightly-pre-COVID album Lover, the feel of the first few setpieces are ambitious. A large dollhouse, as featured from her video from the titular track, backs her for much of the set. Apparently this house has been treated as some kind of skeleton key for Swift’s future songwriting, with her albums since “filling in” each room of the house, according to both various fan posts and winking endorsements by Swift herself.

“Swift is a theater kid at her core,” Rachel noted near the top of the show, and I think Eras is incredibly successful at presenting this truth about her as her biggest strength. Swift’s songwriting takes the extremely personal and private moments of emotional tumult and engages with them as the biggest things to ever happen. Her lyrics on heartbreak, anger, and sadness often flirt with violent imagery, and even when they don’t, they aren’t afraid to get big, treating the tumult of teenage and twentysomething love with all the scope and scale of a show-stopping broadway number crossed with a midwestern emo band.

Her songwriting style hasn’t always worked for me, but when set against the ambition of these sets, it’s hard not to respect it. From the moss-covered piano and fading shack imagery for folklore and evermore, to the Toy Story 2-esque “trapped doll” iconography from “Look What You Made Me Do,” to the fake car on LED screens destroyed by backup dancers to evoke the “Blank Space” video, Eras bathes everything in iconography. The performances themselves are massive, entertaining spectacles whose energy is infectious, choreographed by the great Mandy Moore (no, not that one).

I highly recommend this terrific article in Archietectural Digest that gets into the design ideas and craft behind the tour, from which I will wholesale rip off the observation that the show constantly moves between the catwalk, a main stage with these constantly alternating stage sets, and a diamond stage in the center of SoFi Stadium that featured prominently for Swift’s solo moments. I say solo moments purposefully, because Swift similarly is happy to share the spotlight here, her longtime ensemble of dancers and singers taking a prominent role in the production.

The pieces are there for a film as focused and immaculately crafted as Stop Making Sense, with the same kind of extremely theatrical presentation (albeit in more of a Broadway sense), with the same kind of artist at the peak of her powers and a strong command of the relationship between imagery and song. And a tighter setlist could feature enough truly stellar performances to make something special.

However there just is absolutely zero confidence in what’s on screen. Wrench cannot stick to a shot when he so desperately needs to. The 1989 concert film is infamous for cutting so aggressively it verges on the avant-garde, but Eras unfortunately does so in a way that is merely frustrating. In an admirable effort to get a truly awe-inspiring and technically astonishing amount of coverage – there were at least 40 camera operators credited, operating GoPros, drones, crane cams, Spidercams, and God knows what else, all smooth motion without the flaws of human operation, all devoted to an endless sense of “scale” to underscore How Big This Was – the film cannot settle into any kind of coherent visual language.

Swift’s stage presence, imagery, and backing ensemble are all strong enough to hold an audience’s attention for extended shots, but the film never allows that to happen. The closest exceptions to this come during Reputation, where in fact the cuts intensify and fit the manic, Max Martin-produced energy of the tracks there.The performers and set are all bathed in red and black and accompanied by creative, strobe-heavy editing that ends up fitting well alongside the sweeping movements Wrench seems to lean heavily on. During evermore and folklore, Wrench also lets the camera rest a little more during Swift’s solo moments at the moss-covered piano, a set piece that in a better film could have been as iconic as Byrne’s lamppost.

Wrench certainly makes decisions that are almost explicitly influenced by Stop Making Sense, as Eras wisely cuts out all the filler here too, eschewing the interviews and canned candid moments, and really all buffer material entirely save for a few brief moments of stage banter. Swift in these moments comes off a bit stilted but in a way that I now find endearing, a kind of aw-shucks attitude that is so transparent that you begin to realize it is, in fact, genuine, even if it doesn’t feel that way. Eras also, like Stop Making Sense, cuts between all three nights of filming nearly seamlessly, sometimes doing so within the same song, which feels a bit perverse if not technically impressive when it works.

It’s a shame the film cannot stick the landing because the tour is an incredible spectacle, and the fact that the Eras experience was highly enjoyable in spite of the unfocused film is because the energy and craft of the performances are undeniable. The film doesn’t have a “big suit” moment of its own mostly because it is entirely big suit moments, with Swift donning apparently 44 different outfits throughout the film.

As far as the songs themselves, I’m not dwelling on them mostly out of a lack of expertise and a desire not to dunk on good music that isn’t always for me, but I do think that unfortunately the framing device of the show automatically makes this an experience best reserved for superfans or people with AMC Stubs passes and large bladders. For every song I found myself really enjoying, there were usually close to as many that lost my interest. That’s not a condemnation of the music or performances as much as it is an endurance test: it’s just hard to make that nonstop formula work without standing room and over twice the length of time.

The audience engaged with the film in a very different way too. It was highly participatory, just like Stop Making Sense, but it seemed to mirror what it was presented with, taking on the movements and demeanor of a big stadium crowd. That means less dancing in the aisles and more waving-cell-phones over heads and signing along. It’s a raucous and joyous energy in its own right, but it’s less infectious.

More notable, however, were the multiple moments during our screening where the IMAX projector froze. The crowd, for the most part, handled it with clearly joking complaints, but visions of enraged Swifties online were hard to keep out of the back of my head as the projector stalls got longer and longer during the second hour of the film. Ultimately the issues ironed themselves out, but rather than taking us out of the moment, they ended up accidentally lending Eras a little bit more of an organic feel in a production that seemed averse to showing its seams.

This is where Eras ultimately cannot escape its fate as a mere Modern Concert Film, in spite of both its potential and vision to be something on the level of Stop Making Sense. It is afraid of letting go of the reins for even a little bit. Whereas the greatest concert films – Stop Making Sense especially – have embraced the volatility of the live show as a way to make it feel like a controlled performance, Eras rejects it at all moments. Whatever errors might be there, whatever signs of humans behind the camera, whatever tells between costume changes, anything there is something Swift wants you to see. She has a firm, exacting control of her image, down to the chips on her painted nails, always leaving her audience breadcrumbs to parse and follow. I imagine this approach can be fun if you’re a fan, taking the ARG approach to your music, but it seems exhausting to me personally, as much as I admire the commitment to detail.

It feels unfair to criticize her for this though when I just spend thousands of words breathlessly praising David Byrne for similar things. I really did come out of Eras with a dramatically increased respect for Swift as a songwriter and artist with a cohesive sense of image. But whereas one could argue that Byrne’s branding is a bit cynical and calculated, it is an indisputable truth for a star of Swift’s stature, both by necessity and by choice. It’s obviously good that she maintains control and distance over her public image. But at the same time, it leads to the inescapable feeling that this, like every release of hers, is a cross-sector marketing event.

It doesn’t help this perception that, in a model that offers both a groundbreaking artist’s cut for its release, and is a worrying sign in an era of theatrical monopolies, that Swift cut out usual distribution channels to release the film directly with AMC. The move seems to have paid off – it’s the largest opening weekend for a concert film ever – but it ends up feeling like this imperceptibly massive object, something that can be observed and attended but not engaged with.

Maybe this is more a testament to my own internal biases, but while it feels like something designed to make theatrical audiences dance, it doesn’t quite understand what gets people to dance – and this is through no fault of Swift’s music, which certainly understands that task.

Maybe you just can’t throw a dance party for millions of people in that way. Maybe stadium shows will always translate like that, and one day Swift will release a small, intimate concert film that will redefine the medium, but I doubt it. Not because I think Swift lacks the chops (far from it), but because I think Stop Making Sense is an anomaly that won’t be allowed to happen again, at least not at an even remotely large budget or scale.

Think about the artists that are given that level of creative freedom and a financial blank check. How many of them could get away with it? An artist like Beyonce is certainly doing innovative work with her visual album releases, but her concert documentary Homecoming sticks to the classic formula of performances and interviews that ultimately turn into something that just leaves you wishing you were able to score tickets to the tour.

The concert film, quite simply, is hard to perceive as a profitable endeavor in any capacity. Stop Making Sense didn’t make a ton of money in its time either. It was functionally a mid-budget indie hit. It takes a certain degree of recklessness to make anything interesting with the medium, and something as big as Eras or Homecoming just costs too damn much for that to happen. If the Eras tour changes that sentiment it offers a template that won’t birth new weirder entries, but instead a commitment to massive events that, more than anything, successfully evoke the feeling of stalling out on a Ticketmaster page looking for nosebleed seats that cost 3/4ths of your paycheck.

Is that the future we’re left with for concert films? Already, the only people who get to make them in ways that get seen beyond being released for free on Youtube are people who can fill stadiums. And even then they still usually just get dumped on Netflix to be forgotten by an algorithm with a goldfish’s memory.

The world is getting smaller as it gets bigger, the crises multiplying in a way that makes the lyrics of “Life During Wartime” feel increasingly vivid. I think that’s crucial to why this re-release of Stop Making Sense is having such a moment, and it’s not simply because of nostalgia. I think there is a striking realization that something like it just might not happen again: the perfect confluence of a band in its prime, a filmmaker with a vision, and even a modest blank check from a studio.

Unfortunately, that well has run dry. There are no more blank checks for dance parties run by weirdos. There are bankable events and bankable stars, and everything else will exist on the periphery. You can and will still find that joy on the margins, and you should seek it out like oxygen. But for one brief shining moment on the edge of our lifetimes, there was an appetite for weirdos, and enough cocaine flowing through boardrooms to get those weirdos seen in theaters across America. What a day that was.

Donald Borenstein is a filmmaker and lapsed writer in Red Hook, Brooklyn. They can be found @boringstein on your social media garbage pile of choice, or failing that, probably outside a 7-11.

A special thanks to Rachel Millman & Lauren Hammonds for contributing essential research to this piece.

The death toll in Gaza since October 7 has climbed to 5,791 with more than 16,000 wounded Al Jazeera reports. Nearly half of the dead are children. Many many others are still missing and feared trapped under the rubble.

This is Mujahid. He was 7y old. We treated him in our #cancer department. This was his last drawing - a message of thanks for the #chemo he received while living in the blockaded Gaza Strip. Last night a bomb was dropped on his home, killing him and his entire extended family. pic.twitter.com/Ge5L9d0lLw

— Steve Sosebee (@Stevesosebee) October 24, 2023

I don't know what the point of it is – because as usual the pen is getting its ass kicked in by the sword right now – but I read these poems by the Gazan writer Mosab Abu Toha this morning. Perhaps you will appreciate them. You can find them in his book Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza.

Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear

For Alicia M. Quesnel, MD

i

When you open my ear, touch it

gently.

My mother’s voice lingers somewhere inside.

Her voice is the echo that helps recover my equilibrium

when I feel dizzy during my attentiveness.

You may encounter songs in Arabic,

poems in English I recite to myself,

or a song I chant to the chirping birds in our backyard.

When you stitch the cut, don’t forget to put all these back in my ear.

Put them back in order as you would do with books on your shelf.

ii

The drone’s buzzing sound,

the roar of an F-16,

the screams of bombs falling on houses,

on fields, and on bodies,

of rockets flying away—

rid my small ear canal of them all.

Spray the perfume of your smiles on the incision.

Inject the song of life into my veins to wake me up.

Gently beat the drum so my mind may dance with yours,

my doctor, day and night.

In less pressing literary news Jack Shalom did a reading of my A Creature Wanting Form short story Thy Kingdom Come on his show Arts Express on WBAI FM NYC the other day. You can listen to it here if you like. I half-jokingly suggested he do it in a Boston accent and I think he actually pulled it off. If you never read that story you can find it here. It's about war but I don't really know what I'm talking about if I'm being honest. I don't have any idea what that's really like.

It was the twentieth anniversary of the passing of Elliott Smith the other day so you may want to go read this one if you never did.

The night he died we went to see The Decemberists at the Middle East Upstairs – which is wild enough on its own to think of them playing there – and they played Clementine. It was of course devastating.