Whether or not you die by accident is just a measure of your power

We have the resources. We have the means.

Is Hell World a valued part of your weekly media diet? Then you know what to do buddy.

Sorry I said the words "media diet."

You may have read this story in the Philadelphia Inquirer a few weeks ago about a a group of friends who raised $17,000 to purchase and erase $1.6 million in medical debt. Inspiring stuff. Not the fact that such a thing as medical debt exists in the first place mind you but the rest of it.

Our man in Atlanta Austin L. Ray (who connected me with the great local reporters who wrote for Hell World on Cop City here and here) read the piece himself and thought: Fuck it let's do that here too.

I'm going to turn things over to Austin here. Then stick around for an excerpt from a fabulous book that should be right up your alley after that. Plus more from me below.

Why?

by Austin L. Ray

I don’t wanna bury the lede, so let’s start here: we are raising money to abolish medical debt in Atlanta and beyond. The “we,” in this case, is How I’d Fix Atlanta, an essay series I started a couple years ago that’s kinda-sorta slowly turning into something bigger than an essay series. For now, I’d love it if you could please click that link, give what you can, and tell everyone you know. Thank you so much.

How does this work? RIP Medical Debt is a nonprofit that uses your donations to buy medical debt on the cheap from hospitals and the secondary market. There are private businesses that do this as well, but for very different reasons. After buying the debt for pennies on the dollar (which goes to show how fake and made up medical bills are in the first place), they then go to the people who owe the money and demand it. Often extremely aggressively.

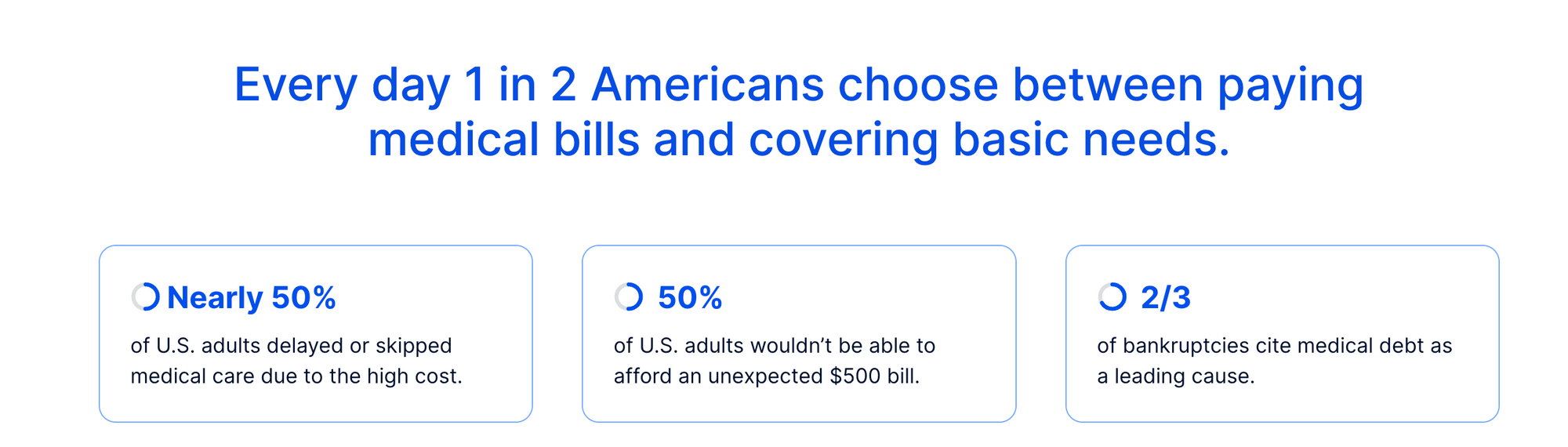

According to a 2021 study, nearly one in five Americans had medical debt in collections between 2009 and 2020 to the tune of $140 billion. One in five. A 2019 study, meanwhile, found that more than 530,000 people a year who file for bankruptcy cite medical issues as a contributor to the problem. Cool system we have here.

Worse than harassing ailing people during some of the scariest times of their lives, hospitals and medical systems often sue patients for the money they owe instead. Take the University of Virginia Health System for example, who sued former patients 36,000 times over a period of six years. Sometimes for a bill as low as $13.

But! In stark contrast to those predatory capitalist monsters betting on and against people’s actual lives, when RIP buys medical debt, they abolish it. They just straight up eliminate it and then send a letter to the person who owed the money letting them know they don’t have to worry about it anymore.

So that’s what we’re doing here: wiping out medical debt. I know that you don’t know me at all but hey you’ve made it a few paragraphs into this thing. Thanks for anything you can do to help. We’ll come back to the debt stuff in a minute.

Have y’all listened to Chat Pile? Great band. Four guys from Oklahoma City who named their noisy, thrilling project after some kind of rock garbage byproduct of lead-zinc mining. The guys in Chat Pile all go by silly pseudonyms—Raygun Busch, Luther Manhole, Stin, and Cap'n Ron—too, which is fun. God, I love this band.

Chat Pile put out an album in 2022 called God’s Country. On that album is a song called “Why.”

Raygun doesn’t sing on this song so much as he rants.

“Why do people have to live outside?” he wonders aloud. “In the brutal heat? Or when it’s below freezing? There are people that are made to live outside. Why?”

Then he starts to sound increasingly agitated. “Why do people have to live outside? When there are buildings all around us? With heat on and no one inside? Why!?”

I think about this song a lot, not only because it fucking rips, but because it so deftly lays out the utter absurdity of just one of the many things we’ve decided to live with in this country.

“Why do people have to live outside?” Raygun says again later in the song, before lowering his voice to a relatively calm level as the band quiets down around him as well.

“We have the resources. We have the means.”

It’s funny, because it’s the kind of thing you don’t often hear adults asking. Maybe because it feels stupid when you say it out loud? There’s an innocence to it, like, no, explain it to me like I’m a child. Why is this happening? Why do we let it happen?

You can point that question in a lot of directions, of course. I could do this all day. Why is public transportation so pathetic in so many big, wealthy cities? Why do cowardly Democrats let deranged Republicans walk all over them constantly? Why can’t we build enough affordable housing? Why do private golf courses still exist? Why do so few politicians listen to their constituents? Why is our healthcare so terrible?

That last one is a topic that Hell World readers are very familiar with, and while the answer is complicated, and I don’t see us clawing our way out of this system any time soon, RIP Medical Debt seems to me like one way to make things a little easier now. I was inspired by a story I read recently about some delightful Philadelphia dirtbags who abolished more than $2 million in medical debt in their city.

One of the Philly organizers is a neurology nurse named Lou Garner who often saw patients with brain cancer. Meeting people whose lives had been turned upside down instantly who also had to worry about whether or not they’d be able to afford treatment was simply too much.

“I once had a girl tell me that she was googling ‘what happens to your medical debt when you die?’” Garner told The Philadelphia Inquirer. “On top of all the other things she’s dealing with, it’s cruelty on top of cruelty.”

I looked at what these Philadelphians did and decided I wanted to try and do it in my town as well. It seems to be working, too. In the first day, we’ve raised enough money to eliminate $1 million in medical debt in Georgia at a cost of only $10,000.

Plus, it was super easy to set up. I filled out a form on their website, briefly chatted with someone on the phone, wrote a few paragraphs for our campaign page, and we were ready to go. Maybe you wanna do the same in your state. Why not?

Austin L. Ray is a writer and dad who grows stuff in Atlanta, GA.

Typical media practice is to run an excerpt of a book before it is published. Then you might run a review the week it comes out. I do not give a shit about any of that. Death to timeliness and news pegs in culture and art writing.

Today's excerpt comes from There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster–Who Profits and Who Pays the Price. The paper back version came out earlier this year but it's new to me and probably you as of this week and you and I after all are the protagonists of reality. Mostly me.

One of the reasons why I wanted to share a chapter here is because the book gets at the main thesis of Welcome to Hell World such as it is. That there are myriad ways to forestall our outsized suffering and pain in this country but we simply choose not to implement them. And that it is always the less powerful who are harmed specifically because of the comfort enjoyed by the powerful.

Jessie Singer writes:

Across the United States, all the places where a person is most likely to die by accident are poor. America’s safest corners are all wealthy. White people and Black people die by accident at unequal rates, especially in those accidents where access to power can decide the outcome—the power to demand that your workplace is safe, the power to fireproof your home, the power to drive instead of walk. Accidents are not flukes or freak mishaps—whether or not you die by accident is just a measure of your power, or lack of it.

It reminds me of something I wrote in the Welcome to Hell World book:

I don’t really know what hell is but I don’t think it’s a place where bad things happen to people randomly such as natural disasters and death because that’s just what the regular world is. I think it’s probably more accurate to say it’s a place where bad things happen because someone wanted them to happen to you or just let them happen out of negligence and indifference. Where bad things happen and they didn’t have to but your life was less important to someone else than what they thought they had to gain.

Alright well anyway here's the chapter. One note: since publication, "accidental" deaths have continued to rise, reaching 224,935 people in 2021. The 2022 aren't expected to be much better.

Not an Accident

by Jessie Singer

This is a book about how we die in the United States. In particular, it is about the significant subset of those deaths we ignore— the accidents. More people die by accident today than at any time in American history. The accidental death toll in the United States is now over 200,000 people a year, or the equivalent of more than one fully loaded Boeing 747-400 falling out of the sky, killing everyone onboard, every day. Americans die by accident more than by stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, pneumonia, kidney failure, suicide, septicemia, liver disease, hypertension, Parkinson’s disease, or terrorism. Yet despite the death toll, there is no fun run for accidental death research or public memorial for the accidental dead. What we call accidents—the traffic crashes, the house fires, the falls and drownings—rarely register as a point of public concern. Why are accidents so common? Why are accidents killing us more than ever? Why don’t we talk about it? And what can we do to stem the rising tide of death and life-altering injury? This book seeks answers to those questions.

We can start with that 747. One of the many reasons accidents fail to register as a cost to society is that they rarely involve a fully loaded 747. Most of the time, when we die by accident, we die in ones and twos. These deaths do not make the nightly news. Rather, accidents are quick and lonely deaths, not reported beyond the police blotter, if at all. To die by accident is to fall down, or get run down, to drink the wrong thing or stand in the wrong place. More than a synonym for a traffic crash or a surprise pregnancy, “accident” is a euphemism for “nothing to see here.”

One person dies by accident every three minutes or so in the United States, the deaths appearing unrelated and not particularly worthy of note. But if we take a closer look at who dies by accident in America, we must take note. Black people die in accidental fires at more than twice the rate of white people. Indigenous people are nearly three times as likely as white people to be accidentally killed by a driver while crossing the street. People in West Virginia die by accident at twice the rate of people over the state line in Virginia, and across the board, the states with the highest rates of accidental death are also the poorest. This book is about that, too—why some people die by accident and others do not.

Let’s start with the simplest question: What is an accident? We can define it by what it’s not: not a disease like cancer, not an act of God like the weather, not an act of intention like murder. But while true, this answer is too simple to encompass the complex phenomena of accidents. “Accident” can be an excuse, an explanation, a mea culpa, or a crime. An accident can generate a legal or emotional response or none at all. If you make a mistake and want forgiveness, you can say: It was an accident. But also, if you wish to forgive someone for a mistake they made, you can tell them: It was an accident. An accident could mean someone wet the bed, or cheated on their spouse, or got knocked up. It is a checkbox on a death certificate and also what happened when BP blew up a deep-water drilling platform and dumped more than 134 million gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has set their doomsday clock at 100 seconds to midnight—one reason is global warming; another is the risk of an accidental nuclear launch. And my best friend died by accident, at least according to the guy who killed him.

That is how I came to write this book.

When I was sixteen, I fell in love with a young man named Eric Ng. He was intense and kind. He was very handsome and very funny. We both had moms from Queens, a habit of sneaking out of the suburbs to go to punk shows on the weekends, and the righteous indignation of young activists. We made quick high school sweethearts and instant best friends.

In time I moved to New York City, and then he did, too. He became a math teacher and I a journalist. At twenty-three, my only life plan was that he would remain my constant.

Then, on December 1, 2006, Eric rode his bike into Manhattan but never rode home. A year later, I sat at the sentencing hearing of the man who had killed him, the wood-walled courtroom divided into victim and perpetrator like a wedding no one wants to attend. Before a judge sentenced the man who killed Eric to jail for driving under the influence and vehicular manslaughter, the man said he was sorry.

“Words cannot express how truly sorry I am,” he told the court, “for this accident that happened.”

It blares in my ear now—this accident that happened—the absence of accountability, the disembodied telling, as if the killer had nothing to do with the killing. But that day in court, I did not question it. I watched the children of the man who killed my best friend nod goodbye to their father and felt certain that Eric would not have wanted this—a man going to prison, more lives ruined, and so little done to prevent this from happening again.

To the epidemiologists who count the ways everyone dies in America, the term of art is “unintentional injuries.” Accidents, by their count, are when a person suffers physical trauma by external force and without intention. In The Injury Fact Book, Second Edition, there is a list of the twenty most common ways to die by accident in America in 1988:

Motor vehicle crashes—traffic Falls

Poisoning by solids/liquids Fires and burns

Drowning Aspiration—nonfood Aspiration—food

Firearm

Machinery

Aircraft

Suffocation

Poisoning by gas/vapor Excessive cold

Struck by falling object Electric current Pedestrian—train

Excessive heat Pedestrian—non-traffic Collision with object/person Exposure, neglect

Epidemiologist Susan P. Baker, a pioneer in the study of accident prevention, compiled The Injury Fact Book. The book was a first-of-its-kind compendium and analysis of accidental death and injury in the United States, an important practical reference for people in the field of public health before the internet allowed access to the records of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Inside, the three times Baker uses the word “accident,” she keeps it in scare quotes—once to let the reader know that when she writes “unintentional injury,” she means what you might call an accident, once to note that the idea of “accident proneness” has been thoroughly debunked, and a third time in a footnote:

The word “accident” erroneously implies that injuries occur by chance and cannot be foreseen or prevented. In much scientific work, the descriptor “accident” is gradually being replaced by more appropriate terms, such as “unintentional injury,” descriptions of the injuries (e.g., “fractured tibia”), or specification of the injury-producing event, such as a motor vehicle crash.

Baker published that volume in 1992, and she would be proven right—today, it is uncommon to find the word in the literature of the profession, at least when the subject is physical injury. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration banned the word from government publications in 1997, and the British Medical Journal banned it from its pages in 2001. The New York City Police Department said they would officially stop using the word in 2013. At a meeting of the American Copy Editors Society in 2016, an editor of the AP Stylebook (a grammatical bellwether for most of the nation’s newspapers) announced that editors should avoid “accident” in cases of possible negligence because it “can be read as exonerating the person responsible.”

And Baker was not alone in her opposition. In 1961, the American psychologist J. J. Gibson put a fine point on it—the word “accident,” he wrote, seemed to refer to a makeshift concept, a hodgepodge of implications legal, medical, and statistical:

Two of its meanings are incompatible. Defined as a harmful encounter with the environment, a danger not averted, an accident is a psychological phenomenon, subject to prediction and control. But defined as an unpredictable event, it is by definition uncontrollable. The two meanings are hopelessly entangled in common usage.

To call something an accident means, at once, that you know it is a risk and that it is out of your control. You would sound ridiculous, but it would not be improper to cite both meanings in a sentence, saying, for example, that you accidentally got into a car accident. Around 40,000 people will die in car accidents in the United States in 2022, and I can predict this because it happens every year. But we would consider each of those accidents an unpredictable event.

The physician William Haddon, the first administrator of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, called the idea that accidents were random and unpredictable, “the last folklore subscribed to by rational men.” He considered it superstitious hooey to call something an accident—a holdover from an era when much of science was inexplicable and mysterious. In his Washington, DC, office he kept a swear jar—anyone who excused a traffic crash as an accident had to forfeit a dime.

But this word-shaming by public health officials has not had much effect in the world at large. Everywhere else, accident remains in common use. In the archives of the New York Times, the number of appearances of the phrase “it was an accident” rises from 1853 to 2009; Google Trends tracks a similar increase in the use of the word “accident” between 2004 and 2021. Despite the opposition of officials like Baker and Haddon, the word has relentless staying power.

And so do, it turns out, actual accidents. It is surprisingly likely that one will kill you.

One in twenty-four people in the United States will die by accident. And among wealthy nations, the problem is distinctly American. You are significantly more likely to die by accident in the United States than in Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, or the U.K. And the gap is significant—in 2008, the rate of accidental death in the United States was more than 40 percent higher than Norway, the next-most-dangerous wealthy nation, and nearly 160 percent higher than the Netherlands, the safest wealthy nation. That year, you were three times more likely to accidentally drown in the United States than in the U.K., more than three times more likely to die in a traffic accident here than in Japan, four times more likely to die of accidental poisoning here than in Canada, and nine times more likely to die in an accidental fire here than in Switzerland.

Yet the U.S. government offers more money for research into the prevention of disease than it does for research into the prevention of accidents. In 2006, of the $11.9 billion in grants issued by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund research into the twenty-nine most common ways to die, injury ranked second to last in amount appropriated, relative to the “burden of illness”—number of people killed and years of life lost. Only depression was more chronically underfunded. AIDS, diabetes, perinatal conditions, breast cancer, dementia, alcohol abuse, dental and oral disorders, cirrhosis, ischemic heart disease, and schizophrenia all received more funding in dollars and relative to the likelihood that any of these will kill you. In fact, as accidents began to rise as a cause of death in the early 1990s, funding for research fell. Between 1996 and 2006, as the rate of accidental death rose, NIH funding for injury-related death research fell by $578 million. This began to shift in 2016 when, after two decades of a growing opioid epidemic, the government passed the first comprehensive laws addressing the problem of accidental overdose, including funding for research. Still, in 2019, injury research received less than half the funding offered to study HIV, AIDS, dementia, or Alzheimer’s—all of which killed fewer people and resulted in fewer years of life lost.

Accidental fatalities and injuries cost us $1.09 trillion in 2019. That is the burden of lost wages and medical expenses, the damage of crashed cars and burnt homes, and the cost of insurance payouts and rising premiums. While dying of disease takes time, and thus costs money, accidents come with the destruction of property, the poisoning of land, the loss of work and income. When survived, accidents also come with the cost of lifelong injury—a loss of quality of life measured at $4.5 trillion a year. Accidents add up to $2,800 per U.S. citizen, per year, in direct costs—out-of-pocket expenses, higher taxes, and more paid-for goods and services. And we pay for it, as individuals and as a nation. Overcrowded U.S. hospitals carry the burden, and municipalities endlessly repairing roadside barriers, expanding the capacity of their fire departments, and buying oil booms to have on hand in case of a spill. The cost of accidents can be counted in taxes paid and wages lost. And because American taxpayers, rather than corporations, carry most of these costs, letting accidents happen is perfectly profitable for corporate America, even when those accidents happen in unsafe American cars or in un-inspected American workplaces.

In 1986, Baker counted 95,277 deaths by accident. Thirty years later, in 2016, the number had grown to 161,374. That year marked a dark milestone. Accidental death had become the third most likely way to die in America. From 1992 to 2020, the number of annual accidental deaths grew by 132 percent, more than four times faster than the population. The rate of accidental death was 79 percent higher in 2020 than it was in 1992. For people age one to age forty-four, it is the single most common cause of death—killing around four times as many people in that population as cancer or heart disease. If you die “before your time,” it will most likely be because of an accident, and today, people in the United States die by accident at higher numbers than ever before. An accident injures ninety-two people every minute of the year and kills twenty every hour.

These numbers and most of the other accidental death statistics in this book come from the National Vital Statistics System of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where epidemiologists track and analyze millions of death certificates a year. Doctors, medical examiners, and coroners produce death certificates, each filling out a cause-of-death section, where they include their opinion concerning “(a) the disease or injury that initiated the train of morbid events leading directly to death, or (b) the circumstances of the accident or violence that produced the fatal injury.” In this book, we will largely leave aside the diseases and violence and concentrate on the accidents and injuries. It is these that added up to more than 200,000 accidental deaths (or what the CDC would call “unintentional injuries”) in 2020, the latest year for which data was available.

Despite this wealth of information, spectacular gaps remain, which left me with places I could not take this book. For instance, medical examiners disagree on the classification of accidental shootings—with some arguing that if someone pulls a trigger, then the death should be classified as a homicide, not an accident, even if it is unintentional, even if the person pulling the trigger is a toddler. This would limit the number of accidental shooting deaths recorded to those that occur when some- one drops a gun or it misfires—but again, there is disagreement on this, so the accidental shooting counts we have are likely a mix of accidental trigger pulls and misfires. That is a small gap—the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recorded just under 13,000 accidental shooting deaths between 1999 and 2019—and even if the number were actually twice as high, it would be a relative drop in the bucket compared to the nearly 2.7 million accidental deaths in that time.

Other data gaps, however, are massive.

In 2016, medical researchers at Johns Hopkins University published a paper calling on the CDC to revise their coding system, which, they said, fails to record as many as 250,000 fatal medical errors a year. This is a significant enough death toll to bump accidental injury out of the top three causes of death in the United States and replace it with medical accidents alone. Medical examiners use a document issued by the World Health Organization called the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (now in its tenth revision and known colloquially as the ICD-10) to code and classify all deaths in the United States. This document simply does not have a code for some mistakes—if you die because your file was missing when a nurse came to assess your condition, or because your doctor misdiagnosed you, or because your anesthesiologist was new on the job.

These mistakes run the gamut: errors of omission, diagnostic errors, communication errors, system errors, and even, simply, bad outcomes for patients whom doctors forgot or who otherwise got lost in the system. But the result of not measuring these accidents is that they are never addressed.

The Johns Hopkins paper offers this real-world example: A young woman felt ill, and a hospital admitted her for extensive tests. At least one test was unnecessary—a pericardiocentesis, where a needle is used to remove fluid from a sac near the heart. The hospital discharged her, but she returned days later, hemorrhaging and in cardiac arrest. While an autopsy found that the pericardiocentesis needle also pierced her liver, resulting in her death, there is no code for conducting an unnecessary high-risk test and causing accidental injury, or accidentally grazing an organ during pericardiocentesis. Doctors coded the cause of death as cardiovascular—not an accident.

Accidents as we know them began to rise in number long before such details were being recorded: with the Industrial Revolution, when workers left behind skilled craftsmanship—on the loom or in the field or at the forge—and stood shoulder to shoulder in assembly lines. As the number of factories grew, so did the economy, and the number of people killed in work accidents, too. In time, some of those factories began to mass-produce automobiles. Then so many died from traffic accidents that cities built monuments to the dead and organized children to march in memoriam.

In those early decades of the twentieth century, accidental death rode high. But in time, lifesaving inventions, along with the shared prosperity brought about by widespread union power, public construction, and social welfare, helped prevent accidents. The rate of accidental death in the United States generally declined during the years 1944–1992. Since then, the rate of accidental death has grown by more than half, even while the overall U.S. fatality rate has generally declined.

It shouldn’t be this way. In 1971, the government approved the sale of naloxone, a drug that can reverse an accidental opioid overdose. The U.S. government first required carmakers to install seat belts in every American car in 1974. In 1995, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) began requiring construction workers to wear safety harnesses. Airbag regulations began in 1998. These are examples of the wealth of harm-reducing innovations that should mean fewer people die from accidents at large, and in traffic accidents, work-fall accidents, and poisoning accidents especially. Yet traffic fatalities skyrocketed in 2020, falls are the leading cause of workers’ deaths in the construction industry, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tallies the death toll of the opioid epidemic at over 840,000 people since 1999, nearly every one classified as an unintentional injury by drug poisoning.

These are the cold, hard facts of accidents in America. But when you look closer, you see that there is nothing cut-and-dried in any one accidental death. The statistical story misses a lot. I found this out the hard way. When I decided to write this book, in the name of diligence, I did something I did not want to do: I sent a Freedom of Information Act request to the City of New York for the records of my best friend’s death. They arrived in a thick manila envelope a few months later. For weeks, I let it sit unopened. At the time, I did not know what I was afraid to find inside—I was right, though, to be afraid.

Inside the manila envelope, I learned that my best friend died on the sidewalk of massive internal injury. I learned that the driver who killed him first told the police that he was not intoxicated, and later said that he’d had two vodka cranberry drinks. Newspapers would later report that he registered at twice the legal limit in a blood-alcohol test. I learned that the driver said that he was going 25 miles per hour but that the distance Eric’s body flew from the point of impact meant that he was driving at least 60 miles per hour. Eric was twenty-two when emergency medical technicians moved his body to the Bellevue Hospital morgue. His killer was twenty-seven and was driving a gray 2000 BMW 528i on the sidewalk.

The police accident report included a diagram. In life, Eric had big muscles and olive skin and a tattoo on his bicep of a cityscape overrun by giant sunflowers, but in the diagram, he was just a stick figure near a drawing of a car and drawings of two bicycle wheels in two separate locations. Far away from the stick figure was a marking for a book bag and another I assumed to be his shoe, Chuck Taylors always, one of which, the report noted, the impact forced off his foot. The police included measurements, marking the distance these items had been thrown when the car hit his body.

There was a deposition transcript in the envelope, too, where the man who killed Eric told prosecutors what he remembered after the crash. He talked about the way Eric had died, described the noises and the movements. He guessed how far away he stood—a few feet—when he watched Eric’s life end.

In time, the man said, a policewoman approached.

“She asked me what happened,” the man recalled. “I said I got into an accident. My car hit this person.”

“My car hit this person,” he said, as though he wasn’t even there.

I did not know any of this when I set out to write this book. The story of Eric’s death that I knew was of an accident—a quick death— because when we talk about accidents, we do not talk about suffering. This was willful ignorance on my part. What happened to Eric was hard to look at, so I looked away. I did not want to think about the suffering. In this way, I understood the man who killed him. Neither of us wanted to look closer. A quick death, like an accident, is a comforting story for the rest of us—a distraction for the survivors, the killers and the grievers alike.

My closer look left me wrecked. It also helped me understand something about accidents that I had not before. It matters who tells the story of an accident. Eric did not live to tell the story of his death, so I never heard how he passed out of this world alone on the cold asphalt. Instead, the man who killed Eric told the story, at least at first—that was a story of a car hitting a person, an accident story, told by a man who had the momentary power of being the survivor. When that man went to prison, the prosecutors who put him there took over the telling—then, the story of Eric’s death was the story of a bad person driving a car, a crime story. In accidents, power, in all its forms, be it a fast car or a plea deal, decides which story we hear. Across the United States, and across history, I found this as a common marker of accidents. The people who tell the story are always the powerful ones, and the powerful ones are rarely the victims.

In this way, surviving a mistake in America is a marker of privilege. On his bicycle, Eric lacked protection and could only travel as quickly as his legs could carry him. Up against a fast car, he would lose every time. His death was a contest of power in its most tangible form. But accidents are the predictable result of unequal power in every form—physical and systemic. Across the United States, all the places where a person is most likely to die by accident are poor. America’s safest corners are all wealthy. White people and Black people die by accident at unequal rates, especially in those accidents where access to power can decide the outcome—the power to demand that your workplace is safe, the power to fireproof your home, the power to drive instead of walk. Accidents are not flukes or freak mishaps—whether or not you die by accident is just a measure of your power, or lack of it.

Excerpted from There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster—Who Profits and Who Pays the Price by Jessie Singer. Copyright © 2022 by Jessie Singer. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

There's an insane thread on Twitter this week – and yes I could probably stop the sentence right there – wherein countless average men are explaining how they walk through the world assessing every potential threat as if they were a soldier on patrol in a war zone.

Question for men:

— The Vorpal Bard 🌿✨ (@BardVorpal) September 23, 2023

My mom, who has been married to my dad for over thirty years, just found out that my dad constantly scans for, assesses, and plans for possible threats

Menfolk, do all of you do this?

I do not do that. I usually just go to the store. I would be very easy to assassinate.

There's a difference between imagining yourself as John Wick every time you go to Costco and living in the U.S. and understandably being a bit wary when out in public on account of the deluge of shootings however. I think it's possible and probably smart to "generally be aware of your surroundings" without living life with the Predator heat vision switched on.

A couple months ago I asked how people have been feeling of late about the grim spectre of sudden gun violence haunting us all. Whether or not anything has changed about how they carry themselves in the world over the past few years.

Some of the answers were like so:

I'm a university professor, and when I teach I have my eyes on the doors constantly now. It started six or seven years ago. I actually had a course I taught moved last year because they put me in a room whose doors were behind the podium. I'm not a moron, I know if a guy comes in with a gun I'm done for. I'm too flabby and stupid to believe I'd stand a chance playing the hero. But you never, ever catch me facing away from the door of a classroom, not even in meetings or at lunch or whatever. For what it’s worth it's not intentional either. It's like looking both ways before I cross the street. It's just automatic

I want to be clear I don't do it because I think I'm going to tactical roll over there and karate chop the gun out of the guys hands. I'd probably just shit my pants and then die. But there was a shooting back then that really got to me and I don't even remember which one now.

Woops! The Canadian parliament honored a Nazi the other day. Like an actual Nazi who fought for the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS. Speaker of the House of Commons Anthony Rota has since stepped down over the whole thing.

I figured that was a good excuse to go back and read Karen Geier writing about the curious persistence of honoring Nazi war veterans in Canada.

These statues are not aberrations: they are a holdover from a time when Canada was very welcoming to Nazi Collaborators. While people are mostly familiar with America’s Operation Paperclip, a system designed to brain drain Germany of its best Nazi scientific minds, Canada similarly looked the other way at Germans immigrating after the war despite their records as concentration camp guards, elite Nazi operatives, and the aforementioned collaborators from Ukraine. There are two reasons for this the government has admitted to: to ‘aid in the Cold War’ and to break labor movements at home. There is another one that looms over that remains unsaid, however: Anti-Semitism. Canada is the country after all which uttered the famous phrase “None Is Too Many” when it was debated how many Jewish refugees from the war to take in.

“Surely these monuments are isolated incidents, and are ‘blips in the system’ which give us a window into a far darker time in Canada’s history,” you might be thinking. “Surely nobody today would be looking to fund, let alone build a monument to Nazis in Canada now.” You would be wrong. Since 2008, there have been efforts to build a Victims of Communism Memorial in Canada. The name is a veil under which lies its true goal: it is an attempt to re-write history by minimizing the role of fascism in World War II, and highlight Communism as the larger evil, mourning the deaths of Nazi collaborators in the process. In the most direct reading of this: it is holocaust denial couched in anti-Communism, funded largely by groups with close affiliation to ex-Nazi collaborators, similar to those depicted in the Nazi monuments. It also just received 4 million dollars in federal government funding (adding to the 3 million pledged by the previous hardcore conservative administration) announced by Canada’s Deputy Prime Minister, herself a PROUD (as she will tell you in her own words) granddaughter of a Ukrainian Nazi, Mykhailo Khomiak who ran an anti-semitic, pro-Nazi newspaper during the war, and who described Poland as being ‘infected by Jews.’ It should be noted that Chrystia Freeland’s party’s slogan is “Sunny Ways”, a shorthand for their ‘egalitarian’ and ‘progressive’ approach to Canada.

Alright I gotta get out of here. See you around man. Hope to see you around.

Here's a nice song for the road.