They don’t see us as equals

Today a dispatch from one of the ongoing protests in Peru that have arisen after the attempted self-coup and subsequent removal from power of president Pedro Castillo in December. At least sixty people have been killed and hundreds of others have been injured largely by police violence.

Help pay for independent reporting like this with a subscription if you can.

A las cuántas muertes te da rabia

by Jimena Ledgard

It feels like all of the air has been sucked out of my lungs in a split second. I lift my shirt up to see if there's a wound. My skin is red and burning but otherwise intact.

“The pellet probably bounced against something else before hitting you,” a photojournalist yells at me over the noise when he sees me checking my stomach. I can hardly hear him. The sound of tear gas canisters and pellets being shot left and right makes the city of Lima feel like a war zone, which it is, in a way.

Nearby a 55-year old man named Víctor Santisteban Yacsavilca will be killed a few hours later by a policeman that fired a tear gas canister at him point blank. Security camera footage will show Santisteban was just standing there, neither resisting nor posing any kind of threat. Closer still 35-year old Rolando Marcos Arango will fall to the ground bleeding and unconscious after being hit by a pellet in the head. This will happen just a few feet away from where I’m standing, at the supposedly safeguarded spot where journalists and correspondents have taken shelter from the crossfire. The moment will be captured on live television, though the TV channel that registered it will cut back to the studio without addressing what happened.

Elsewhere in the city several independent journalists will be attacked by the police, to the silence of mainstream media channels. Human rights defenders and protesters waiting outside the nearest hospital will be hit with batons and dragged along the ground by the police.

Over 60 people have died in Peru since social unrest reached a boiling point in mid-December. 47 were killed by police action during the protests, most of them from firearm wounds. 10 died from issues related to the dozens of nationwide roadblocks which have been popping everywhere, with government leaders unable or unwilling to open up humanitarian corridors.

One policeman was also killed, his body found next to his charred car, allegedly burned alive. All but one of the deaths have happened outside of Lima, the country’s capital.

It’s not easy to pin down the exact moment that kicked the country into its present downward spiral. Peruvians can’t even agree on that, not even when it’s clear that the attempted self-coup and immediate ousting of former president Pedro Castillo by Congress on December 8 was what started the current two months of social unrest and protests. For some, that day brought on the current crisis; for others, particularly those I meet and talk to on the streets, the coup attempt was the inevitable outcome of a much longer conflict.

“The elites have made it very clear. They will never allow one of us to be in power,” a 55-year old man tells me during one of the protests. He has come to Lima from Puno, the country’s southernmost region and one of the poorest, where 18 people were killed by the police on a single day in early January. “They don’t see us as equals. They don’t even see us as people,” he tells me. His voice breaks, I can hear the frustration. I don’t know what to do but nod.

Many of the protesters around me are indigenous and have traveled for days to reach the capital, some carrying nothing more than the clothes they were wearing when they left their homes. They wave rainbow-colored flags that represent the Andean communities. Some of them wear traditional embroidered skirts and vests. They have been sleeping for days on the ground of empty parking lots, surviving on potatoes they’ve brought from their hometowns in sacks, struggling every day trying to find their way in a ruthless, sprawling city. One of the first protests they tried to hold in Lima never even started: they didn't know which way to go or where to regroup when riot police broke them up. There’s no central organization, and a deep-seated distrust of potential allies in Lima.

Castillo was by all accounts a weak president, facing serious accusations of widespread corruption. A self-proclaimed leftist, his feeble attempts at implementing policies during his short-lived year and a half presidency were not particularly progressive nor radical. The surprise winner of the 2021 presidential election, a year after taking oath he was still excusing any misgivings on his inexperience.

And yet thousands of Peruvians saw themselves represented in his presidency. When white, middle class urbanites mocked his way of speaking or the fact that he still wore the traditional hat of his Andean community during his first public appearances as president, thousands of indigenous and rural Peruvians felt the insults were directed at themselves.

“He was one of us”, a protesters from the Andean region of Cajamarca tells me. “He speaks like myself and like my parents and my grandparents. Why was that supposed to be shameful?”

I make my way through the crowd. People dance and play instruments and hold signs and chant. The mood is aggrieved but festive, because what else can you do in the face of death and grief other than remind yourself that you are alive? Groups of traditional musicians, known as sikuris, march down the street, singing and playing wooden Andean flutes and large drums. Their songs send chills down my spine. They always have. They’re a sorrowful call to arms, a reminder of the burden and love that is intergenerational resistance. I lose myself in their music for a few minutes. If some proclivity to cynicism might reside within me, sikuris are always able to stop it from taking hold.

Your children are fighting now, the Andes are shaking. Oh, my people, the Andes are shaking. If I was born crying, I will have to die fighting. The injustices of this world will forever be gone. Oh, my people, they will forever be gone. Oh, my people, let’s end them for good.

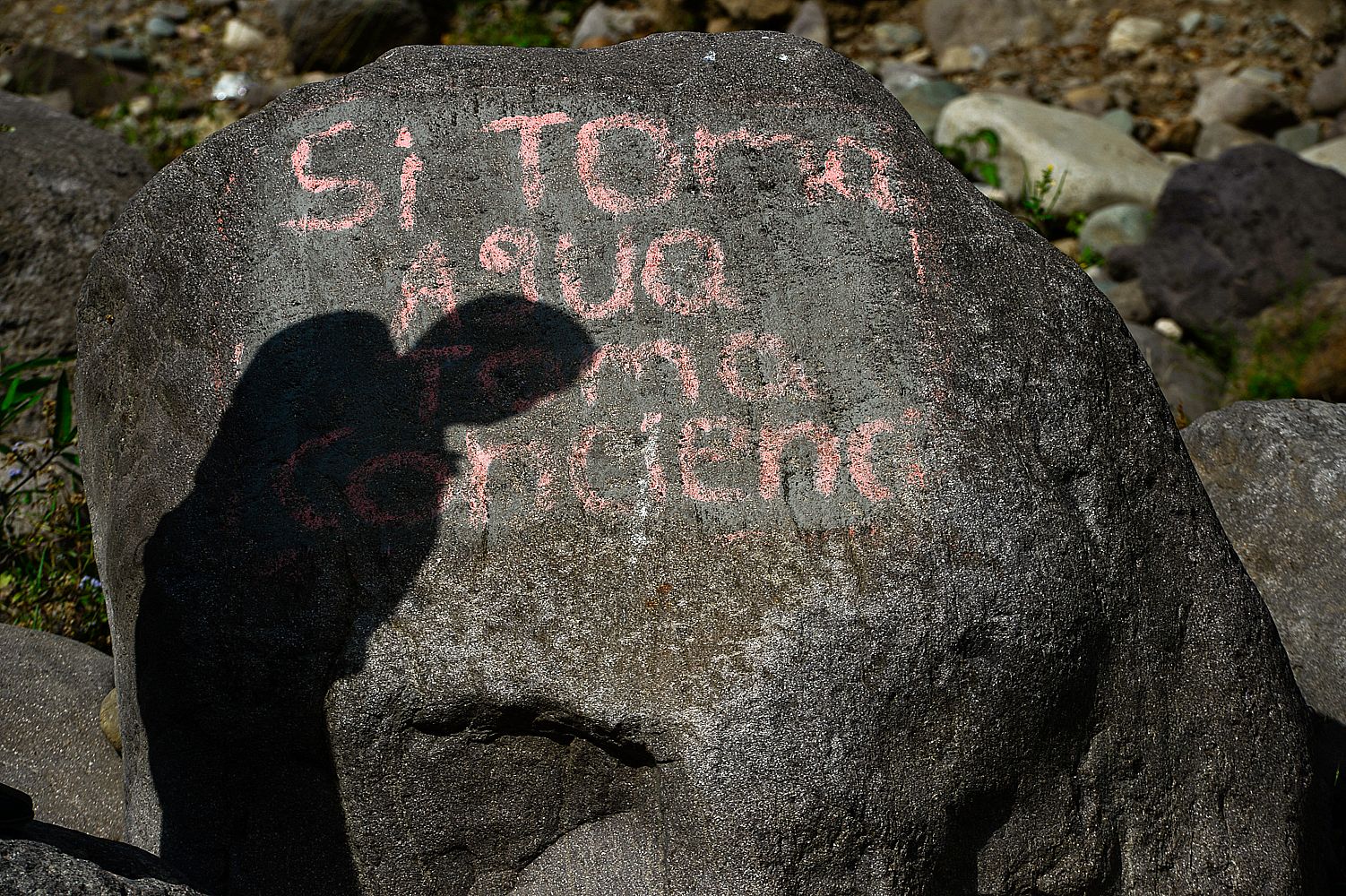

After leaving them behind, I pass a woman holding up a handwritten sign with large red letters. “At how many deaths do you get angry?” (“A las cuántas muertes te da rabia”) it reads.

I think about the deaths. A woman, her head blown off in Macusani, Puno. A video of two policemen using a rifle to shoot at protesters from inside the town’s police station went viral that same day, but the government never addressed it. The media reported on how the protesters burned down the police station after one of their own was killed, but skimmed over the shooting. A young doctor, who wasn’t part of the protests, but had left his house to care for a wounded demonstrator just outside his door, also dead. People shot in the back as they tried to escape police repression.

A 21-year old man, still fighting for his life, 36 pellets inside of him, lodged deep inside his kidney, intestines and liver.

I hear stories of a doctor in an Andean town that’s treating people in his own house, as protesters are too afraid to show up at the hospital in fear they will be detained. It’s hard to know what’s true and what isn’t. During one of the protests I attended, however, a pellet opened a hole in the cheek of a man standing next to me. He plainly refused to go to a hospital, though I swear I could see the insides of his mouth.

In Lima, the protests are peaceful until they’re not.

Peru has had 6 presidents in 4 years. An unintended consequence of this constant state of crisis is that protesters have become much more adept at resisting attempts to disband or stop them. Learning from the frontline or primera línea that formed during the Chilean social upheaval of 2019 and 2020, they deactivate tear gas, drowning the canisters in water and sodium bicarbonate; build barricades and block roads; throw stones and break police barriers; resist behind homemade shields made of cardboard and foam; kick back anything that’s shot at them; light firecrackers to confuse the riot police.

But most importantly, protesters challenge the state’s right to the monopoly of violence and renounce the moral high-ground offered by peaceful resistance. In return, some are detained on terrorism charges.

“We will not give up. If I have to go home in a coffin, so be it,” a young woman tells me. She arrived a week ago from Ayacucho, a region ravaged in the eighties by terrorist group Shining Path, and then struck again by tragedy this past December when 10 protesters were killed in a single day of police repression. “We know what terrorism is. They have no right to use that word against us.”

She joins a group of protesters passing by. I hear their chants as they leave me behind.

“We are not terrorists. We are peasants.”

Jimena Ledgard is a writer and journalist based in Lima, Peru. Her work focuses on social unrest, illegal economies, the environment and inequality. You can check out more here and can often find her on Twitter or Instagram.

More in Hell World on Central and South America: