Honduran water protectors detail their time as political prisoners

By the time they arrived in La Tolva, a maximum security prison usually reserved for the most dangerous criminals in Honduras, Orvin Hernandez, Porfirio Sorto, and six others were the most famous political prisoners in the country. After organizing their villages against an open pit mine constructed illegally in a nearby national park, the water protectors were convicted of a series of bogus, politically-motivated charges. For the next three years, including three months in La Tolva, they witnessed multiple murders, torture, deprivation, and a military invasion of the prison.

Jared Olson reports from Honduras after talking to a few of the since-released political prisoners about their ordeal.

If you missed the most recent issues of Hell World Brad Searles wrote on the passing of Mimi Parker and I talked to a zookeeper.

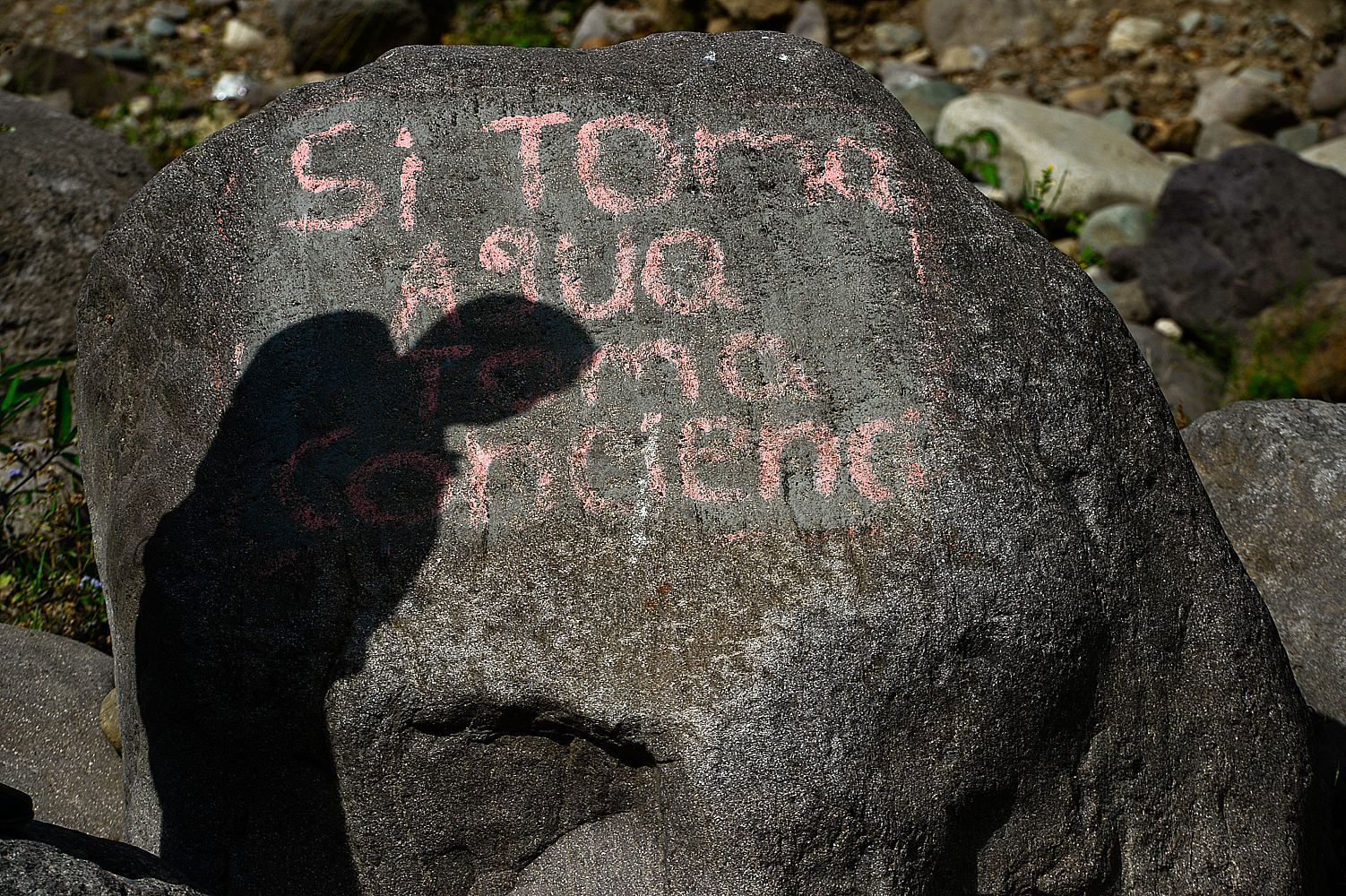

Ver, Oir, y Callar

by Jared Olson

Things had been tense ever since the armed men showed up and the wave of assassinations began.

Members of the community watch for Guapinol, a quiet village near the north coast of Honduras, had already been trading audio messages on WhatsApp about the sudden appearance of a suspicious vehicle, so when an unfamiliar car rolled past Kelvin Romero, near where he’d been manning a lookout at the end of a dirt road, his fears were confirmed. It was just days before the camp above their village — where they were blockading a road to protest the construction of one of the most notorious open-pit mines in Central America — would be broken apart by soldiers and police in a hail of teargas and gunfire. Things, so far, weren’t going well.

The car stopped after going another fifty feet. From the passenger side, a masked man in civilian clothes stepped out with what appeared to be an Israeli assault rifle. Romero could see he was wearing a bulletproof vest with the insignia of the FNAMP, or Fuerza Nacional Anti-Mara y Pandilla (National Anti-Mob and Gang Force).

Honduras has become notorious not just for its staggering criminal violence, but for the willingness of the government itself to openly murder, often in conjunction with said criminals. The FNAMP, a defunct military unit purportedly meant to fight gangs, became emblematic of this corruption after being accused of working with MS-13, a major streetgang, and operating as a death squad.

The sight of someone in the area with FNAMP paraphernalia was curious to Romero, considering there were no streetgangs in Guapinol, nor anywhere in the Aguan Valley where they lived, nor hardly anywhere in the entire department of Colon. But this was a right-wing narco-state supported by the US. It didn’t matter if there were actually criminals, because some of the biggest criminals are the members of the state themselves.

The masked man brought his rifle up to his shoulder and started shooting at Romero, so he and a friend bolted off through a cornfield along the road. They struggled through brittle stalks of corn as the shooter ran after them, stopping now and again to shoot, the bullets whizzing past their heads one by one.

Breathless and terrified, they eventually managed to escape into the village. But Romero’s problems were only beginning.

For two years, Guapinol and several other towns had been pushing back against the mining giant, Pinares Investments, a company that was seeking to dig an open pit mine in Carlos Escaleras National Park, in the mountains above, that would threaten to contaminate the river that runs through Guapinol and thirty other communities. Pinares was owned by some of the richest people in Honduras. It was protected by the soldiers and police of a right-wing narco-state supported by the US that had come to power after a 2009 military coup. It was slated to export materials to Nucor Steel, one of the largest steel corporations in the world. It surprised few people then, less than a year later, when Romero and seven others resisting the company were sent to prison under spurious pretenses.

Defending the environment in the US or Europe is difficult enough. But doing so across the poor Global South, where environmentalists resist encroachment of mining, agribusiness, or tourism into their lands, has become deadly. Since 2012, at least 1,733 environmental defenders have been murdered by assassins, organized crime, or their own governments, according to a new study by Global Witness. The majority of the deaths took place in Mexico, the Philippines, Colombia and Honduras. A land or water defender is murdered an average of once every two days, though the report noted that the death toll is most likely an undercount.

The problems don’t stop if you aren’t killed. Environmental defenders in the Global South are still sucked into the vortex of what's come to be referred to as “criminalization.” Criminalization has become common in Central America, whereby environmental defenders are demonized through fake or misleading news reports published by local journalists who have been “bought off,” or by armies of bots on social media, or by police departments who issue dragnets of arbitrary arrest warrants, often requested by the rich and powerful in conjunction with organized crime. One of the most famous cases of criminalization happened to Romero and his friends, who came to be known as the Guapinol Eight. When they couldn’t be killed, they were thrown in jail.

The struggle of the Guapinol Eight soon became emblematic of the struggle of poor, rural Hondurans against a mine being built in a highly biodiverse national park, but it was also a window into the corruption, violence, and environmental destruction writ large causing people to flee the region.

Over multiple visits this year I’ve documented the stories of five of the eight former prisoners: Orvin Hernandez, Porfirio Sorto, Kelvin Romero, Lino Cedillo and Daniel Marquez. The prisoners have since been granted amnesty in a choreographed move by Honduras’ ostensibly democratic socialist President Xiomara Castro earlier this year, and they’re now back living in the rural villages where they were before their imprisonment. This is the first time the story of their time in jail has been told.

***

There will likely never be a full investigation of the killings that began in 2018, but a swarm of anonymous social media accounts were more than ready to begin accusing the Guapinol water defenders, like Romero and friends, of being the culprits behind those murders, which included fellow environmental protestors, mineworkers, and military policemen. In August 2019, after being charged with crimes related to the vanquished highway blockade from October 2018, the men delivered themselves to the authorities in the capital of Tegucigalpa in an effort to demonstrate what they insisted was their innocence.

As Romero told me, there was a bizarre lack of urgency on the part of the authorities in the process, especially considering the gravity of the crimes they were accused of — kidnapping, arson, robbery. When they arrived that morning, expecting to be treated like violent criminals, they were told to sit down and wait for processing in the same way a receptionist talks to someone visiting the doctor, he said. They were supposedly “criminals… but they don’t want to attend to us yet,” he said. When the authorities got around to putting them in handcuffs, they sent them to Tamara, a sprawling medium security penitentiary complex in the piney mountains north of the city.

They would spend thirteen days in Tamara, which might not have the worst reputation of any prison in Honduras, but murders and torture behind bars don’t raise eyebrows here. Local reporters have established it is likely run by MS-13.

“You felt a certain vibe of danger,” Lino Cedillo, one of the prisoners, told me in the barber shop he runs in Guapinol. When we talked in August, Cedillo, who speaks in short, stoic, laconic statements, said he still was recovering from what he called the psychological trauma of being in prison.

“As someone new to this, you’re afraid of everything.”

The men I spoke to all recalled having to quickly learn the rules of living in gang-filled prison. One rule reigned above all: Ver, Oir, y Callar.

You see something, you hear something, you shut up.

Anyone who talks about the gangs, in other words, would face the gang’s full wrath.

“Almost every day there were dead people there,” Porfirio Sorto, also from Guapinol, told me later, recalling the frequency with which he saw bodies taken out of the prison, without knowing how or why those people had died.

The prisoners were brought into packed rooms where the sheer quantity of people made it difficult to sleep. (Some of the men remembered there being thirty people packed into these rooms, others a hundred). But they largely avoided problems since word of their story had filtered to the guards and even to some of the prisoners.

“That’s just the law in Honduras,” Romero remembers the guards saying glumly, meaning that the law means little here.

Their lawyers had made an appeal to move them to Olanchito, a lower-profile prison in the Upper Aguan Valley, an hour drive away from the majority of their families. They assumed the request had been accepted, because on their thirteenth day in Tamara, the eight of them were led out of prison and placed onto a military truck.

Waiting for them in the bus were ten or so soldiers wielding M-16s. The military police, or PMOPs as they’re known by their Spanish acronym, are a notorious, widely-feared unit whose creation is considered to be the pet-project of conservative former President Juan Orlando Hernández, who is now in jail in the US for drug trafficking. Hernández had been a US ally for years, but after he’d supported US-promoted policies — militarizing security and having the military on the streets to ostensibly fight crime; stripping environmental and labor regulations in the name of “economic competitiveness”; turning Honduras into a bottleneck against northbound migrants — he was thrown under the bus and seized by the DEA. (The move drew comparisons to the downfall of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, a CIA asset who helped fund anti-communist guerrilla armies in the 80s, but was ousted in the US invasion in 1989 when the Cold War was over and his geopolitical usefulness had been exhausted). Understandably, given their origins, the PMOPs were accused not just of abetting the narco-trade — they’re also accused of torturing and executing protesters.

Hours before the prisoners should have arrived at their final destination, the truck stopped in the middle of nowhere. The prisoners remember the military police making them file off the bus in shackles, taking a photo, filing them back on, and then back off again. And then a third time. Some of the guards, they noticed, were smirking.

Minutes later they turned off the highway.

“Here’s your beloved Olanchito that you wanted so much,” the military police taunted them. They were all laughing now.

They weren’t in Olanchito of course. The hulking complex coming into view as they swung into the parking lot was La Tolva, or El Pozo, a maximum security penitentiary reserved for the worst criminals in the country like assassins and high-level gang members. It was reputed to be one of the most dangerous prisons in Honduras, making it one of the most dangerous prisons in the world.

The guards funneled the men inside, stripped them naked, and gave them uniforms to wear. Because Porfirio Sorto was the last of the group, he had to remain in the clothes that he already had.

Sorto and Orvin Hernandez were transferred to a section of the prison that was run by MS-13. (MS-13 controls four sections, while Barrio 18, their biggest rival, controls another four. Prison guards keep watch of the multiple security checkpoints leading inside, while the external perimeter of the prison, at the time, was guarded by Honduran military).

When Sorto and Hernandez arrived inside, the coordinator of their section, who was an emeese, the slang used to denote a member of MS-13, saw that Sorto was still wearing his normal clothes and decided to lend him a uniform.

“You don’t belong to the Mara (the gang), no?” the coordinator said. Sorto replied in the negative, explaining that he and his friends had been imprisoned for defending their villages from a toxic mining project.

The coordinator also said the uniform he gave Sorto was temporary. “You have to get another because it identifies you as being with [the gang],” he reportedly told Sorto. The type of uniform was used to differentiate which gang prisoners belonged to. Three days later, Sorto got a normal uniform from a younger man, though by that time he was so terrified that he remained hidden at the back of his cell.

In another section run by MS-13, a coordinator informed Daniel Marquez of some ominous news. “We’ve been given orders to torture you,” he said. He never specified where those orders came from. But, they said, he’d leave them alone if they shut up and kept to themselves.

Ver, oir, y callar.

Romero is still struck by what one of the gang members told him upon arriving, as he told me.

“No one leaves here except in body bags,” he remembers him joking.

La Tolva, meanwhile, was hell. All day gang members jeered and hurled long-distance insults to members of the opposing gangs through the metal walls. There was no sunlight. The only sight of the sky that they got, according to Orvin, was an hour every eight or fifteen days, when they were allowed outside to play soccer with the other inmates from their section of the prison.

One day during a feverish prayer in prison, the prisoners crying and moaning in ecstasy, the pastor leading the prayer — an evangelical in jail for a reason no one knew— said he had a vision. The Saint of Death had informed him that there would be a murder soon, at the end of the stairs down the hall at the entrance to the clinic.

Eight days later Sorto saw the same coordinator who’d given him the uniform walk out in the company of six other men. He didn’t think much of it until a few moments later when they heard the air explode with a blitz of gunfire. The coordinator, according to other prisoners close by, threw down a pistol he’d used to kill another gang member.

For a pistol to have gotten that far into prison would have entailed going past not just five layers of security checkpoints but also the soldiers keeping guard outside.

At the time things were getting worse in Honduras’ prison system. The same government that supported the Pinares mine found itself swept into violent narco-intrigue. The killing at the entrance of the clinic came three days after the assassination in another prison of Magdaleno Meza, a former drug trafficker who had a Narco-libreta, or “Narco booklet,” which had a list of names of people in the drug trade that — supposedly — implicated then President Hernandez.

The incident would be watched and re-watched by millions. On security cameras that captured his last moments, masked policemen moved Meza to a closed off room before ominously swinging open a sliding metal door. Several gang members rushed in, opening fire on Meza with Uzis, emptying their magazines into him before stabbing his body and reducing it to swiss cheese. Tony Hernandez, the President’s brother, was already in prison for drug trafficking in the US, and the President had just been named as an accomplice. The murder was widely seen as a message from President Hernández as to what would happen if someone decided to rat on him.

After the killing at the clinic and the Meza killing, the military moved in from the perimeter and invaded the prison. The ex-prisoners I talked to recall hundreds of soldiers with M-16s pulling inmates out into the hallway, lining them up, yelling at them, and patting them down for guns.

Someone high up had sent the Guapinol Eight to La Tolva, through a loophole in Honduras’ weak legal system, that was never entirely explained. The ideas was to “torture them” indeed. Three days after the killing in the clinic, they were put on a bus and shipped off to the prison in Olanchito.

***

Olanchito was more mellow, but only by a hair. And beyond the bars, outside, Honduras was burning.

By 2019 caravans of poor Hondurans were fleeing the country, braving teargas and batons of the Mexican National Guard to escape poverty and violence at home. By 2020, the pandemic meant that many Hondurans, who have no savings and work day to day on the street, were left to starve in their homes or — if they wanted to keep working on the streets — get shot or beat up by the police for breaking quarantine. Catastrophic hurricanes after the pandemic caused a new wave of caravans, which were repressed by batons and teargas at the Guatemalan border.

But in Guapinol, according to local organizer Esly Banegas, “the pandemic was a gold mine for Pinares.” With community organizing slowed by the killings and the imprisonment, she said, the company was able to build the processing plant and begin the road into the mining concession in the mountains. When I visited in October 2020, Reinaldo Dominguez, a resident of Guapinol who was against the mine, described how patrols of army trucks came rolling through the village after the murder of yet another anti-mine activist just a few days before.

But things seemed like they could change for the better. In November 2021, against all odds, Xiomara Castro won the election, becoming Honduras’ first female head of state.

Not long afterwards, the trial for the Guapinol eight began in a courthouse in Tocoa. The trial would last until late February, and ended in their conviction — though just days later, in a surprise move, Castro would grant the prisoners amnesty. Soon after her government announced an “end to open pit mining.” Around this time President Hernandez, one of the main backers of the mine, was seized by Honduran police at the behest of the DEA. A crowd cheered at the chain-linked fences of the airport in the capital Tegucigalpa as the former President was whisked out of the country to face trial in the US.

But things in Guapinol would soon become dark. After the ecstasy of their liberation, it became clear that Castro’s declared “end to open pit mining” was mere political theater meant to accompany the liberation of the prisoners. Because mining in Honduras — with all the violence and corruption associated with it — was actually going nowhere.

Today the open pit mine above Guapinol continues to expand. At the same time, Juan Orlando’s military police — who Xiomara ultimately decided to keep deployed in the street— continue to patrol the perimeter of the mine’s installations. As an inside source in the government environmental agency MiAmbiente told me, the mine is already established, and isn’t going away. It’s too late.

Romero, for one, sees the outlook of the struggle against the mine in dark terms.

“As the mine continues to grow and affect the communities here, there’s going to be violence,” he told me at his home in Guapinol, not far from where he was shot at before he was taken to jail, four years ago. It takes little imagination to imagine what might happen when communities are displaced by the mine in a region swarming with armed groups.

“And when that happens, I’m leaving.”

Jared Olson is a writer and investigative journalist with a focus on human rights in Central America, primarily Honduras. His essays and reportage have appeared in The Intercept, The Nation, The New Republic, Foreign Policy, Al-Jazeera, and more. Find him on Twitter: @jolson321