Watching the very moments of an era’s extinction

Representing the American present

You could probably publish an anthology of near speculative fiction right now titled The Day It Happens and sell 100,000 copies.

I wrote something to that effect which I'll share down below. Today's main thing is a really smart and moving essay about watching the television series Girls for the first time in 2025. It's not just about that though obviously. Like any good Hell World piece it's also about the oppressive wildfire smoke and homelessness and our addiction to our phones and the inability of art to capture anything resembling the realism of the present anymore.

Except of course for We Had It Coming (OR Books 2025) that is.

It goes in part like so:

"Watching Girls I felt no nostalgia, or even its inverse, which is the shuddering relief that you don’t ever have to return to a certain time and place. I felt lurid fascination. I was watching the very moments of an era’s extinction. Those years now seemed to me like the last time any aspect of the present in America could be reasonably imagined, represented, and thus meaningfully depicted."

I was going to put this one behind the paywall but I really don't like doing that with such good work from guests. On the other hand I gotta pay money to the fucking writers so you can see the predicament we're in here. Here it is for free but if you feel moved by the spirit to purchase a subscription anyway that would be great. Enjoy 33% off one year to celebrate Hell World's birthday month.

33% off a year of Hell World!

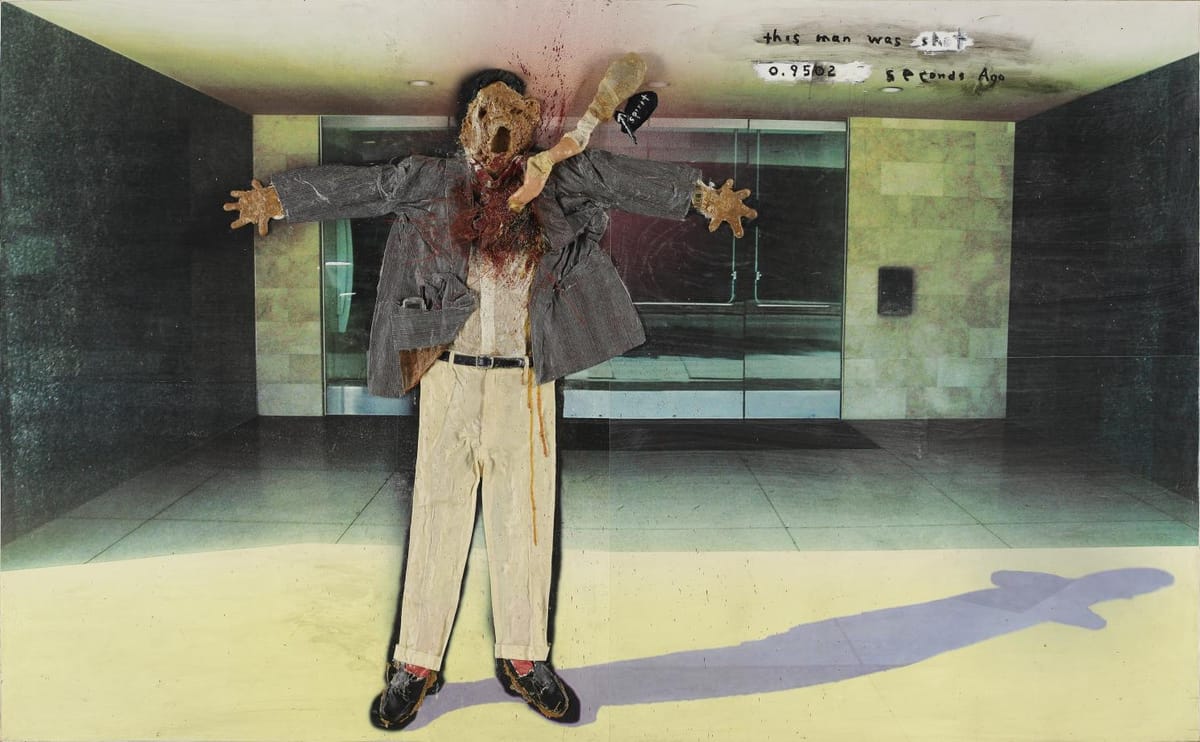

Did I share this one from my new book We Had It Coming – out in a month or so! – already? I don't remember. Who cares I suppose. It's also about wildfire smoke.

Hold on a minute though. Check out this great piece in Defector about the creative team behind Zohran Mamdani's videos including Hell World contributor Donald Borenstein. It's written by another Hell World contributor Corey Atad.

Borenstein also references the films of Wong Kar-wai and Christopher Doyle’s lush, urban cinematography. Then there are the less expected influences, like the Canadian mockumentary series Nirvanna the Band the Show, and Adult Swim’s Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!

“Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim are two of the most influential filmmakers of the 21st century,” Borenstein said, referring to the duo’s unconventional style of cutting, quick push-ins, and the general “roughness around the edges” that gives their work a real DIY feel. “More than anything, I just watch a bunch of dumb comedy. That's why wipes and whip pans and stuff are such an important part of the visual language.

“I love that kind of beat, and I think it can be deployed even in ways that are disarming and earnest,” Borenstein said.

Borenstein wrote for Hell World about his favorite David Berman songs:

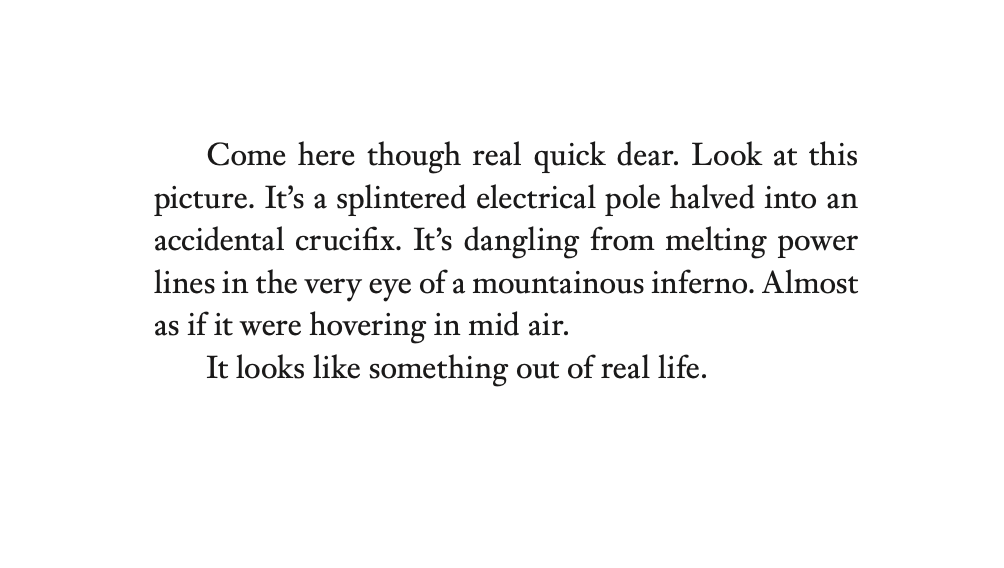

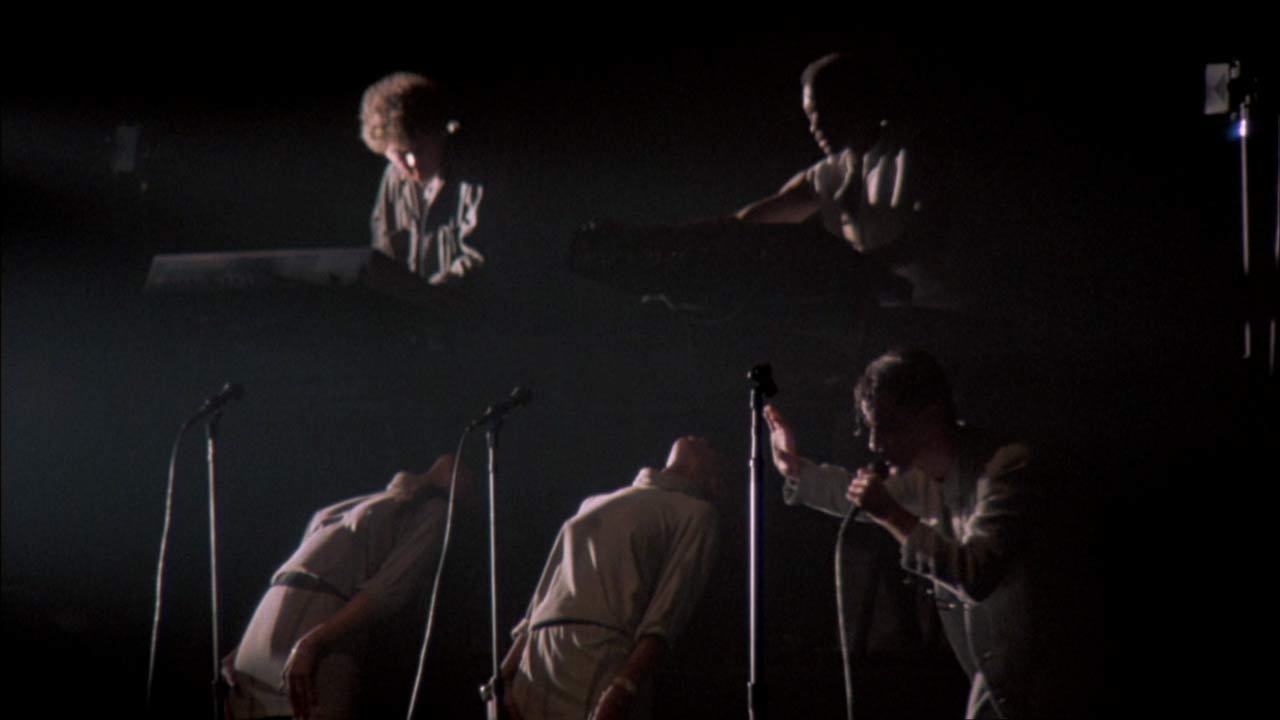

He also wrote this great one about Stop Making Sense:

Atad wrote about the life and work of David Lynch:

He also wrote for Hell World about the films Se7en; The Zone of Interest; Megalopolis; and the series The Bear.

I sometimes think I share old pieces of note in here too often but the reason I do that is simple: I want to people to read them DEAR.

Alright please enjoy today's main feature now. Stick around for more from me after.

Representing the American present

by John M. Ganiard

Last month, in a now semi-annual fit of cabin fever, I succumbed to watching the entirety of Girls, a show I sort of assumed I’d never bother to get around to. Much of Manitoba and Saskatchewan has been on fire this summer, the second-worst wildfire season in the country’s history behind only 2023. I live quite far away from it all in the American Midwest. Like that season two summers ago, debris from uncontrollable forest incineration has been rising high into the atmosphere and drifting southeast with the wind. The smoke and lofted ash are exposed to prolonged sunlight, and the particulate matter breaks down into the toxic volatile organic compounds benzene and formaldehyde. Our small town has become desaturated in the haze, like a picture slowly overexposed.

I was a smoker through the bulk of my twenties, but I find myself staying inside when the AQI – a metric heretofore foreign to your average midwesterner – gets bad enough, which is to say frequently.

As for Girls, in the intervening years since its final season, all of my excuses not to watch it have melted away entirely. I can barely even remember what they were. Much like any memories I have of the “blogs” or “alt lit” or “indie sleeze” of its concurrent cultural epoch have been overwritten by the daily unremarkable hits of dopamine from innumerable trips to the casino of the infinite scroll. No longer a phenomenon of discourse cycles, Girls now appeared to me like a harmless cultural artifact, something I could escape into under the guise of wistful research or critical analysis.

The show wrapped in 2016, and its last season aired in early 2017. It would be easy to suggest, reflecting on its legacy, that it was as if its creators believed their saga of nominally apolitical Brooklyn gentrifiers extended infinitely into a somnambulic Clintonian future, just as one’s own naive experience of selfhood entails it never really ending. But by the end of the series, Lena Dunham’s Hannah Horvath has left New York for an academic job upstate, where she tries to raise a child with the help of a best friend traumatized by her own narcissism and self-mythologizing.

In the final episode, Hannah’s mother visits in a fit of protection indistinguishable from shame and disappointment. Love, in other words. All three women seem deep in the wreckage of just how long it takes to ever “come of age,” poised for a durable and minorly transformational reckoning, ready to shake loose a bit from the manic American id and form real community.

And then it's over.

Girls is the closest any Judd Apatow production gets to artful social realism, a debt it owes almost entirely to the show’s creator, show runner, and brilliant comedic lead. Its best episodes, including the finale, are more like Mike Leigh films than they are This is 40 or similar works that otherwise fully retreat into the tidy utopian resolutions of a Hollywood comedy when all is said and done. I was surprised by how much of it felt viscerally “true” – emotionally at least – to someone who was that exact age at that exact time. It smartly channeled the special ignorance of the era, reifying it through its characters. It achieved, in effect, a selective realism. While maximalist representation of its time was never Girls’ purview, it’s not hard to finish the series and imagine Hannah’s well-paying non-adjunct job and well-appointed house off campus wiped out by austerity and contraction, less than a decade away; to sense the long-reaching fissures of the series-preceding 2008 financial collapse exploding into the revanchist, absurdly suicidal fractures of today. The potential energy is there, permanently suspended in a near-alternate 2017.

“What I mean by realism,” the French director Maurice Pialat once remarked in an interview, “goes beyond reality.” For Pialat, the aesthetic already developed in the minute-long work Employees Leaving the Lumière Factory, in some sense the big bang of moving images, “provides the definition of cinema: an alchemy, a transformation of the sordid into the marvelous, of the common into the exceptional, of the filmed subject into the very moment of its extinction.”

Watching Girls I felt no nostalgia, or even its inverse, which is the shuddering relief that you don’t ever have to return to a certain time and place. I felt lurid fascination. I was watching the very moments of an era’s extinction. Those years now seemed to me like the last time any aspect of the present in America could be reasonably imagined, represented, and thus meaningfully depicted. This is quite likely the very thing I doubted as I dutifully avoided it. It was a doubt that overwhelmed and shrouded the show’s reception each season despite its success. And despite some critics at the time adeptly recognizing it as at once a “bold defense (and a searing critique)” of its millennial subject matter, as well as a show “attuned to a narrow type of rarely-seen-before verisimilitude” belied by the contemporaneous culture’s constant need to “receive” it “through a lens of unyielding literalism—as if the show were the world.”

Whatever else it was – a serial comedy chiefly interested in the disconnect between unlikeable, college-educated, artificially precarious white millennials and their near misses with the real world from which they are all humorously insulated – Girls offered up a generative and rewarding dialectic. But we’ve perhaps long maintained a delusion about there being a serious “real world,” a stable status quo ante reality that unserious or insincere people and ideas would either be sharpened upon or cast aside by, and this delusion no longer holds. Girls is one of many texts made in and about its particular 21st century present that seems perched on an event horizon we’ve all since slipped past, still visible to us as we descend into a bottomless gunk of collapse we fear will never really be replaced by a “future” (complimentary) and never truly become the “past” (derogatory).

A young couple, probably in their mid-twenties, is living on the hedge-encircled landing of a single-level midcentury office building a few blocks from me, under the sign for a tech startup that has yet to return to its still fully-furnished office. Sometimes they scream at each other late at night, wandering into and down the middle of the street, the only place they have approaching privacy. I think about their chests eventually rising and falling as they lie on their backs on the concrete eking out some sleep. Smoke from an ancient forest suspended over them and visible under the bright LEDs of the streetlights. Their Bluetooth speaker still playing ads.

It’s a college town, and although we used to have a full-size newspaper, most people I talk to now get their news from the local subreddit or the city’s official app for reporting compliance issues. On the former, every other thread this summer that isn’t entitled “weird fog today?” is an exhortation to jail or involuntarily commit the unhoused, now that the number of people in states of profound distress or illness one might visibly encounter has increased by single digits. Our downtown, to these users, is “no longer safe,” despite always being busy, the summer weekend street closures thronging with shoppers and bar-goers.

On the latter app, encampments fashioned with considerable effort to be invisible or out of the way – one’s best option given the lone shelter is overcrowded, under-resourced, and not always safe – are geotagged near daily with fervent requests that they be dismantled immediately. This despite the city commenting on nearly every post of this kind that the app is not meant to be a place where tents and encampments are to be reported, per se.

On days when the smoke is thick, I’ll watch strollers blithely pass by on the sidewalk outside, joggers struggling and rubbing their eyes. Two summers ago, I might have worn a mask on an errand into town during an orange alert. Now I’ll only do so for a red. I work from home near my apartment’s mechanical room. I think about the benzene seeping out from the water heater pilot all day, under the door, floating toward my desk invisibly, compounding the exposure from all the benzene I voluntarily drew into my lungs for years, compulsively, so that I might neutralize a few stray intrusive thoughts. I think about my dentist hearing out an unrelated question I had about my bite guard, reflexively and defensively interrupting me to ask, “Is this about microplastics?” I tell myself I am learning that part of living is accepting all the various ways we are and will be poisoned. This is all just the same eternal duḥkha; these are relatively easy problems to have, I try to reason. I’m just getting stuck thinking about what is chosen and what are the unchosen forces of history haunting us; I’m just searching for unattainable moral exculpation. The white plastic takeout fork in the mind, beyond the last thought, rises.

Just try to ignore stuff like that.

And then I’ll reach for my phone, which delivers a reliable bright blue beam of outsourced rumination:

You need to release the pain in your cervical spine; you need to release the suboccipital muscles (with the help of a professional) caused by your bad posture and poor breathing technique; stop scrolling and witness that I am dying by your government’s hand; stop scrolling because the dopamine drip is neurochemically trapping you in the stress response and do this breathing exercise instead; a miracle happens when you stretch this weird piece of metal; psychologists say you need to do this one thing to regain community and escape the isolation of your childless late 30s; the cozy hippo baby refuses to be moved; your phone is slowly destroying your capacity for normal human thought so re-download this app blocker you used to pay money for to get work done and which now advertises itself as explicitly Christian.

I try and fail to develop preliminary theories as to what I even mean:

The present evades meaningful depiction because it can no longer be authentically experienced other than through our phones; the present evades depiction because we refuse to accept or acknowledge it sincerely and with earnest curiosity, or else we are prevented from fully doing so by forces beyond our control; the present is so infinitesimally fragmented that its ephemerality can no longer be adequately captured in traditional, long-form media.

Each strafes just past the problem I am struggling to describe.

So much of This American Present has become a numbed and therapeutic passing of time, and passing the time is purgatory, fundamentally unrepresentable. Smoke blows in from the north. Our wages are garnished to pound an entire people into another kind of toxic ash. The economy enthusiastically hosts a parasite covering its body in hideous, server-farm-sized cysts, and it is infecting the world with brainrot. Horns of twisted, procedurally generated content grow aimlessly from its skull. America’s ability to accurately depict the melting, era-less, infinite bleed of the present in our most frequently consumed media just feels off in some way, drastically attenuated.

It is still often best captured within the very platforms that worryingly represent our ongoing lobotomization. What stands out is the work of comedians and a shitposter creative class, resigned to poisonous new media, emitting primal screams from deep within our phones: collages of ugly corporate app UI, satirical AI-voiced nostalgia farming (“remember the pencil crank?”), a slideshow of incel chan outsider art at 5x speed like a sleeper cell activation sequence, Conner O’Malley’s uncanny depictions of manic Wilmette-area adult entertainment convention enthusiasts and braindead flat-brim grindset podcasters – the transcended zen masters of our pornified society. Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal and How To with John Wilson allow their seemingly straightforward and traditional long-form narratives to be corroded by the acid of our heavily mediated online existence. In so doing each show uncannily captures the perilous slippage of our attention, the rot besetting our capacity to reason and genuinely connect. While undeniably brilliant, the cumulative effect is nauseating, like watching someone trace intricate patterns in the blood pouring out of an open wound.

Meanwhile, there’s an increasing and compensatory decompression effect to the rest of American television, which my girlfriend and I have long resolved to stop watching with dinner in favor of actual emotional co-regulation. HBO’s The Pitt and FX’s The Bear work hard for an appearance of made-by-humans unmediated realism. Each is set in a sector of the economy devastated by the pandemic, following the crushing burnout of the people still in those industries and shell-shocked by recent events; flawed but inherently good characters who, like us, often lack “healthy work-life balance.” Each deploys frenetic, documentarian steadicam, though The Bear is frequently punctuated by elegant, painterly composition (note that strict documentary itself has long done this). They are enjoyable and well-made, well-acted and competently written. They announce themselves as meaningful depictions of the present. You can almost dismiss a sinking feeling you get that they’re effortfully concealing the pandering didacticism of hopeful marketers, yearning for normalcy on our behalf from a subtle, morally overcorrected day-after-tomorrow. You can put aside the pacification of these shows, because it’s nice to have a heat sink and de-stress from your chronic cortisol overload with the paresthesia conferred by someone else’s more acutely undeserved suffering, someone who is both your kinder analog and ultimately isn’t real.

Of course, why not allow each of these to represent some version of an always-shattered present, and accept there’s no synthesis to be had, no accidentally synecdochical record of the now; how far off is that from the imperfect keyhole glimpse a 2010's bourgeois sex comedy seemed to steal of its time?

“Do you think we’re capable of depicting our present, this present?” I ask my girlfriend. She hesitates. “Well, I know this is a special interest of yours.” She asks me again for the reasons I think those depictions now tend to fail, and I rattle off a few. “See,” she says, “those are the same things I thought about Girls when I stopped watching it back when it was on. Maybe what happens is that some things only seem perceptive and insightful with the benefit of hindsight, after time has passed. Maybe you’ll just have to wait.”

This is possibly unrelated, but she often reminds me that the world has always been ending, and that apocalyptic thinking “is not allowed” in the apartment. I think about that tired old idea from philosophy, the abyss. We are being stared back into by something dark and terrible; there is no doubt that it is growing, and part of the power it continues to draw is from our willingness to stare too long into it, confusing it entirely for the world to come.

The sunsets this summer are a vivid, unreal red, thick smoke scattering the blue light. What I’m feeling, and resisting, is in the end just another form of nostalgia—a desire for the hysterical ignorance of life now to be cast in amber and mostly forgotten, suddenly beautiful when rediscovered.

Trapped back in the scroll the other day, I saw a post about an otherwise minor detail of a painting. In the right panel of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, on Hell’s horizon, the Netherlandish master painted beams of light emanating from a ruined city and illuminating the clouds above, capturing in near-exact detail scenes from the actual wars of the 20th century 400 years before any such image would be possible to witness in reality. Someone speaks something hopeful through the abyss: we are trying to depict the present, earnestly working to communicate its meaning, succeeding and failing, long before it ever arrives.

John M. Ganiard lives and works in Michigan.

Here's a little something I wrote back in 2019 about The Day It Happens: