The destruction of USAID and my grandfather's legacy

by Colette Shade

This piece will go out in the next edition of the Hell World newsletter. Consider a free or paid subscription to support our work.

Read Kim Kelly on the murder of Renee Nicole Good from yesterday if you missed it.

Every so often, my family has the same discussion: Was Papa a spy?

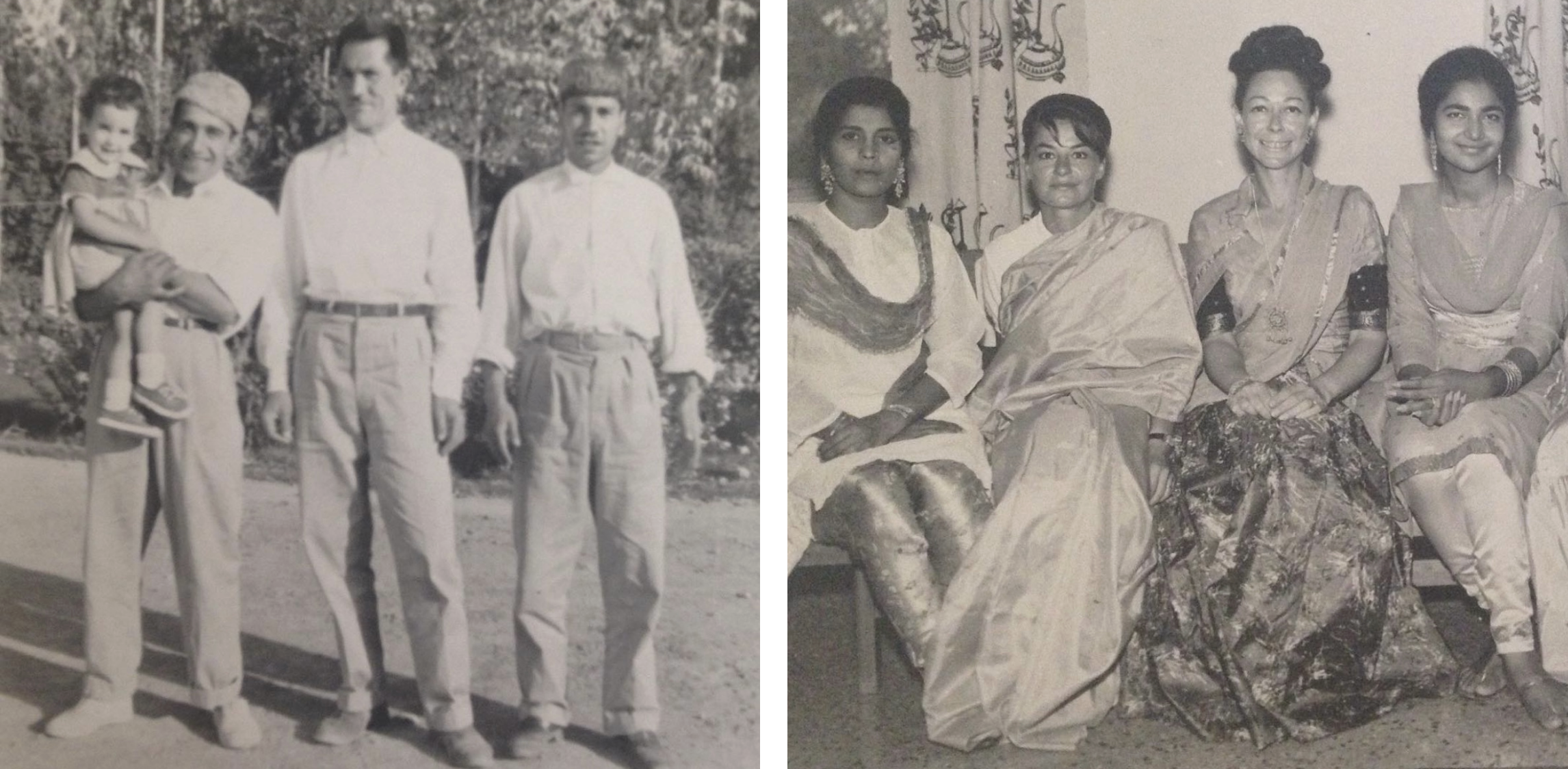

Papa was my mom’s dad. He worked, for 20 years, for the State Department, and specifically USAID, the United States Agency for International Development. This subagency was founded in 1961, with the intention of using global development and humanitarian aid to win hearts and minds during the Cold War. Papa was an MBA-trained economist who spent his career helping developing countries do things like build dams and increase agricultural yields. Between 1958 and 1978, he worked in Kabul, Karachi, Lahore, Lagos, Vietnam and Georgetown, Guyana, each two to three year assignment alternating with one to two years stateside in places like Brooklyn, Bethesda, and Palo Alto. His final title before retirement was the vague-sounding “Deputy Director of Mission.”

To foreign policy-knowers and the Pynchon-minded, these details scream CIA. After all, it’s been known for decades that the CIA at times used USAID to gather intelligence in other countries. Many of the places Papa was assigned had major Cold War strategic relevance. He took a mysterious trip to the Soviet Union in the early 60’s. And, after he retired, Papa talked for a while about writing spy thrillers in the vein of John le Carré.

My husband, an MBA student, historian and onetime Marine intelligence officer, is convinced Papa was a spook, or at least that he worked with CIA people. Nana, my grandmother, disagrees, because “we knew who all the spies were” in the foreign service community. My mom’s brother has his suspicions, as does my dad. My mom, on the other hand, says circumstantial evidence isn’t enough to support a claim. Papa died in 1996, so we can’t ask him, not that he would have clarified anything. He tended to keep things close to his chest.

Mostly this conversation comes up toward the end of a holiday meal, or on a long car ride, or after people have had a couple drinks, the same way you might argue about whether Die Hard is a Christmas movie or something. It is low stakes and fundamentally unanswerable; more a way of amusing ourselves and bonding and filling space than anything else.

Lately, though, the question of whether or not Papa was a spy has been on my mind a lot. USAID has been in the news this past year, perhaps more than it’s ever been in my life. The reason for this is that Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), has functionally destroyed it. On February 3, 2025, just weeks after Trump’s inauguration, Musk bragged on Twitter that “we spent the weekend feeding USAID into the wood chipper.”

Leaving aside the fact that this unilateral decision by an unelected billionaire is completely illegal, the effects have been disastrous. Before DOGE showed up to do massive layoffs, USAID employed about 10,000 people. It now employs around 15. Pregnant USAID staffers found themselves without health insurance or paychecks. Some staffers were left to fend for themselves in war zones. Many of these people have highly specialized skill sets and cannot simply pivot to the private sector, because the private sector has no use for them.

The effects were even worse for people in the countries USAID serves. Entire communities lost access to HIV medication, cancer treatment, and routine healthcare. In Kenya, there is now an ongoing hunger crisis because of cuts to food aid. Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health estimates that hundreds of thousands of people have already died due to the USAID shutdown alone. A study at UCLA found that, if the defunding continues, it will cause 14 million preventable deaths by 2030, 4 million of which will be children under age five.

A very smart friend of mine (a lefty professor) posted on Facebook about the consequences of USAID’s destruction shortly after it began. This friend was, to be clear, decrying it. But I did something foolish, which was to scroll down through the comments, where I found someone else replying that, yes, it was horrible that all those people were going to die, but USAID was a front for the CIA, you know, and was essential for propping up U.S. hegemony. So good riddance.

I don’t normally obsess over random people’s Facebook comments, but that one still bothers me. I think it’s because I run into that sort of argument with some regularity on the left. I’m not a huge fan of U.S. empire, and yes, I of course have my prejudices because of my family history. But I think the destruction of USAID was a horrible tragedy. Not just for the reasons I’ve said already, which people basically understand, but because I think USAID’s destruction marks the end of a way of being — a subculture as well as a life path — that was basically good.

And yes, the U.S. invaded sovereign countries in the 20th century, but at least we also gave people food and healthcare and schools and dams. Now, all we do is war crimes, and we don’t even bother to try to use international law or our supposed role as a global steward as a justification. Sorry to the “we’ve always been like this” people, but kidnapping Nicolás Maduro, murdering random fishermen, and threatening to invade Greenland mark a significant change for the worse! To paraphrase something else I read on social media recently, the only thing worse than liberal U.S. empire is an illiberal U.S. empire.

Like a lot of American Jews, Papa was born in Flatbush, Brooklyn, in 1927. He came from the sort of family where nobody had gone to college, and where you sent your kid to the orphanage if you couldn’t afford to feed them. Papa got good test scores though, so he got into Brooklyn Tech for high school, and then went into the Navy, but the war ended when he was still in basic training. He finished his period of service, then used his GI bill to get a BS in geology at Brooklyn College, then an MBA at the University of Texas. In Austin, to make money, Nana did the books for a guy who ran a company that sold restaurant supplies to fraternity houses. When that man asked if she was Jewish, she said no.

“Good,” said the man. “They killed the lord, you know.”

After he graduated, Papa took the foreign service exam. Again, he was good at tests, so he got to the interview stage, and he aced that, too, even though, traditionally, foreign service was a career for guys who went to Andover and Yale and could trace their lineage back to the Mayflower, not for the children of immigrants whose kids played handball in garbage-strewn lots. But it was the 50’s, and institutions — especially those within the federal government — were starting to open up their ranks to ethnic whites, providing they were good at test taking. Later, after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, this offer would extend to nonwhite Americans as well.

These days, most people I like recoil from the term “meritocracy.” Racists hear the term “meritocracy” and think it justifies their worldview. They point to the racial wealth gap as proof that we all get what we deserve, and that white people are clearly just more deserving than nonwhite people of wealth and status. The idea that America rewards people based on their merit alone is laughable. Even before Trump II, the State Department is just one institution that has been accused of racist and discriminatory hiring practices. When I speak of meritocracy, it is not to say that we ever truly had one.

Meanwhile, a certain type of liberal admits that there isn’t a meritocracy right now, but would be perfectly okay with one providing that those in power were an exact demographic representation of the country. They’re fine with most people having no healthcare and getting evicted and working three jobs, as long as they, too, are an even sample of the population. This is not something I agree with either. I believe that everyone deserves healthcare and housing and a comfortable wage no matter how good they are at standardized tests, and also that standardized tests are just one way of measuring human capability.

When I speak about meritocracy, it is to say that I believe in the importance of expertise and competence, and that I think it was good that we even sort of tried to have a system where those things could be rewarded, especially compared to this bullshit we have now where you have to go to Mar-a-Lago and eat overcooked steak with the president to get a leadership role in our government.

In 1958, Papa got his first assignment: Kabul, Afghanistan. My mom was two years old and her brother was six. The parents packed up the family’s Brooklyn apartment and then got on an ocean liner, a jet, and finally a rickety propeller plane full of chickens and goats. Ten days later, they touched down at Bagram Airfield, amidst the towering Hindu Kush mountains.

In many ways, it was a charmed life. Though Papa’s salary was modest, the family lived in a house whose rent was paid fully by the U.S. government. My mom and her brother attended the local international school, which meant their classmates were British and French and Italian and American as well as Afghan. Most were the children of government employees or diplomats, but some were also the children of missionaries. Nobody had television, so the foreign service people entertained themselves by putting on plays for each other like Macbeth (Nana played one of the witches) and Guys and Dolls (Papa played Nicely-Nicely Johnson; Nana, a Hot Box Girl). Hours were passed with bridge for the ladies and poker for the men, golf foursomes and tennis doubles, and, most of all, cocktail parties. Nana told me that while Papa was at work, one ambassador would ride his horse to her house to drink martinis and flirt with her. One time, she met a painfully awkward man standing in the corner at a party, and, feeling sorry for him, struck up a conversation. It turned out to be Dag Hammarskjöld, secretary general of the United Nations.

These dynamics would be more or less repeated at each posting. The foreign service is its own subculture, especially when you’re a kid. You’re not totally part of the country you come from, but you’re not totally part of the country where you live, either. You’re always kind of looking at things from the outside, but at least when you’re at an international school abroad, you’re with other people who share these experiences. When my mom came back to the States, one of her new classmates in Maryland asked if Afghanistan was near Texas.

As a little kid, I was always confused when I heard that term. “The States,” I mean. My uncle and my mom would use it when they told old stories. It sounded like they meant another place far away, when what they really meant was right here, the country where we all lived now, the only country where I had ever lived.

There were stories they told that made no sense to most Americans. For example: the story of the India-Pakistan War of 1965. There was a curfew, and they had to put tar paper on their windows, and they missed so much school that everyone had to do Saturday school to make up for it.

“Because of war,” my mom emphasizes.

She takes a kind of pride in telling this story, just as she takes pride in telling how they had to evacuate their first house in Karachi because it was filled with deadly vipers, or of how she lost part of her finger in a fight with her brother over a coveted box of Sugar Smacks, which had to be ordered from the PX, then waited on for six months while it travelled by cargo ship and plane. Or how they couldn’t have lettuce because of cholera, how they drank powdered milk, how they had to get so many shots you’d have to get them all at the same time in both arms, and she’d always sing “These are a Few of my Favorite Things” so she wouldn’t be as scared. How you’d have to keep your shoes turned upside down because of scorpions. How she first heard the song “Light My Fire” by the Doors over a military radio station. How you’d make a best friend and then always have to leave them.

My uncle has stories too. Like how, in second grade, all the kids left school to go to the birthday party for the son of the French ambassador, and all the 7 and 8 year olds, following the cultural custom, were given a glass of wine with their cake, and they all fell asleep with their heads on the table. Or the story of my uncle’s 10th birthday present in Karachi. There were no American-style toy stores, so Nana went down to the bazaar to buy him a donkey, thinking it would make a nice pet. He was thrilled, but a few days later, he went outside to find the animal had died of dysentery.

Foreign service, as a subculture, forces you to become curious about other people and other places. It forces resourcefulness, adaptability, and curiosity. It forces you to become cosmopolitan. In other words, it forces you to adopt qualities that many people — especially many Americans — have no need to develop.

There can be a kind of superficiality to this cosmopolitanism. There can be something self-congratulatory. I can spot a foreign service person’s house from a mile away, because it looks like Nana’s. On the wall are African death masks, Afghan saddle covers, prints of Thai dancers, and punched tin folk art from Mexico. Some people act like their souvenirs prove a deep understanding of other cultures, as deep an understanding as they might have if they were Afghan or Thai themselves. And this can prevent foreign service people from seeing how the locals really feel about them.

When Nana was in Pakistan, she learned some Urdu. Years later at a party she attended back in the States, the white host showed off a tablecloth she had bought that was embroidered with Urdu script. She asked Nana if she could make out any of what it said. Nana sounded it out phonetically.

“Yan-kee-go-home.”

All things being equal, though, I think foreign service cosmopolitanism acts as a kind of inoculation against the worst parts of American jingoism and racism. After 9/11, my mom was baffled by the fear and hatred of Muslims that overtook American society. These people had been her neighbors, her teachers, and her classmates, and had been perfectly normal people. She found the government’s explanations for the attack simplistic (“they hate us for our freedom”) and historically uninformed. She bristled at the chauvinistic displays of patriotism, being taught, as foreign service people were, to always act gracious, like a guest. When American flags were going up on cars and houses across Northern Virginia, she refused to participate, insisting that such consumerism would cheapen both the tragedy and her pride in her country.

This is the kind of person produced by the foreign service as a subculture. I think it is not a mistake that one of our best U.S. senators — Chris Van Hollen of Maryland — is a foreign service brat. He is the son of an American diplomat and grew up in Karachi (like my mom), as well as Sri Lanka, Turkey, and India. He has been one of the only mainstream national politicians to speak out about the genocide in Gaza, and to encourage the U.S. to stop funding it. He also flew to El Salvador to meet with his constituent Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who had been imprisoned there by the Trump administration.

I think, too, of Joe Strummer. He was born in Turkey to a father in the British foreign service, and grew up there, as well as in Mexico, Egypt, and Germany. The Clash was musically omnivorous, mixing their punk rock with influences from rap, blues, disco, dub reggae, and calypso. Strummer wrote songs about topics like the Spanish Civil War, U.S. involvement in Latin American coups, and anti-immigrant racism in Thatcherite Britain. The band released an entire album named after the socialist Sandinista movement in Nicaragua. Maybe Joe Strummer still would have made great music if he had grown up in Britain, but it’s hard to imagine him fronting “the only band that matters.”

When I think about DOGE and what it did to USAID, I think of all this. I think about how my family history now feels illegible. USAID was one of the few places where Americans were encouraged to learn Urdu or listen to calypso music or consider what it’s like to live in a war zone. To get rid of USAID is an attempt to turn our attention inward, and to celebrate cruelty, stupidity, and incuriosity even more than we already do. It’s an attempt to turn us all into the kind of people who think Afghanistan is near Texas.

Colette Shade is the author of Y2K, a collection of essays about coming of age in the Y2K era. You can find her on BlueSky.