It’s cozy in here and I hate it

Pop-up pop-art; Sex Change and the City; You Are in a Museum

Back a little sooner than usual with a busy one today on account of I'm bad at scheduling and have no chill and yet I have a couple cool pieces I want to get out the door to you nice people.

Read an excerpt from the moving and funny new anthology Sex Change and the City below or go right to it here.

First there's this:

"I don’t know if I’m any good at going to museums anymore."

That's true of me in real life but also in the obviously mostly me character in one of the stories from my new book We Had It Coming which you can read down below or jump to here.

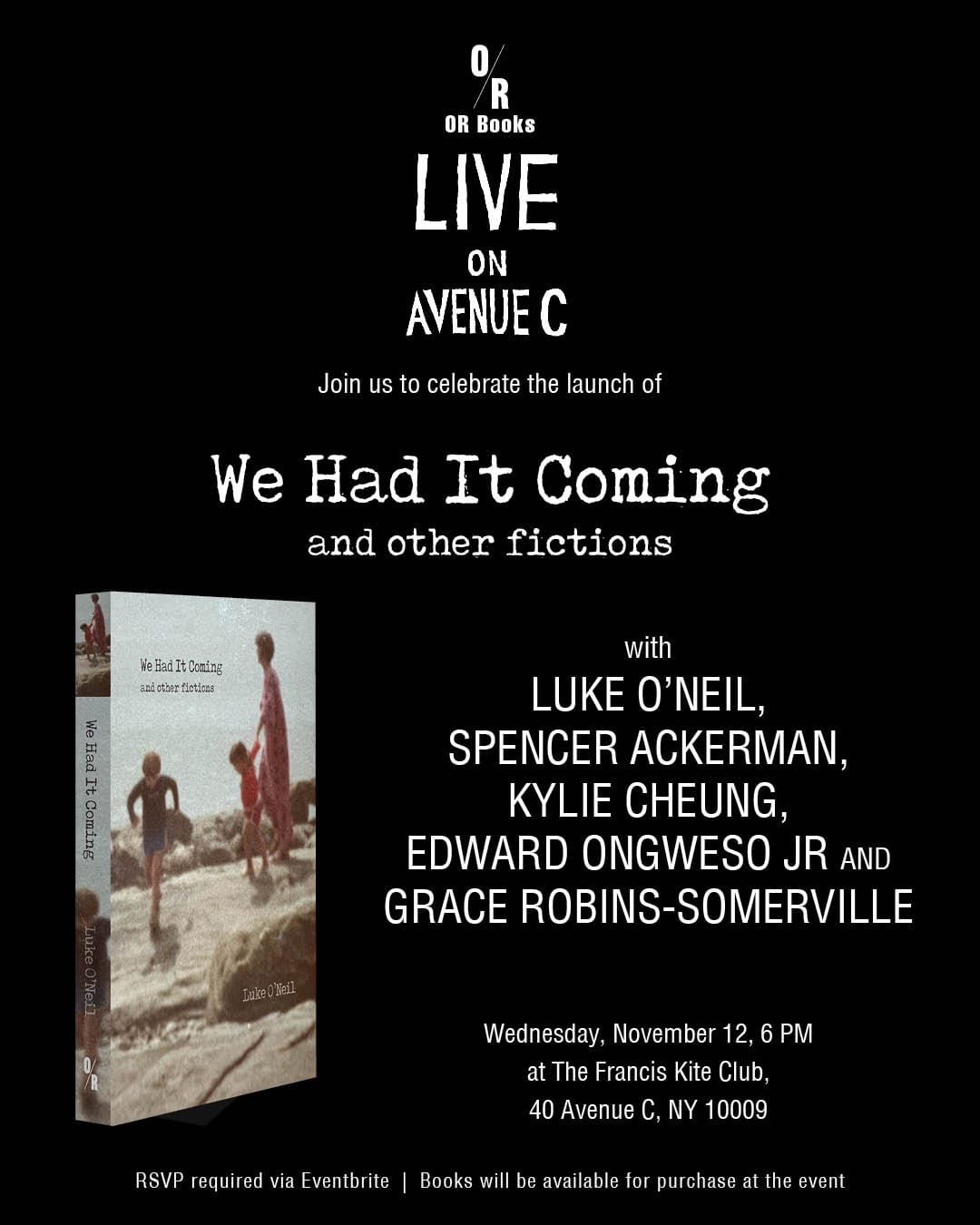

We made a zine to celebrate Luke O’Neil’s new short fiction collection featuring illustrations from inside the book! Order the book today: it's SHIPPING! orbooks.com/catalog/we-h... @lukeoneil47.bsky.social

— OR Books (@orbooks.bsky.social) 2025-09-25T18:51:19.996Z

If I can barely stand looking at actual art there's no chance for me at one of these pop-up pop-art experiences that have become common in recent years. Steve Coy went to one in San Francisco and wrote about the antisocialism, infantilization, and conflict avoidance of the current state of sloptimization.

He previously wrote this funny piece about a very important and necessary new development in recycling with the launch of an AI-powered recycling kiosk!

Please pay for the writing that you enjoy. Here's 25% off a subscription.

My book events thus far will be in NYC at the OR Books space on Ave. C on 11/12 and in Cambridge at The Sinclair on 11/8. Let me know if you live in Philly or D.C. and would come out to one.

It’s cozy in here and I hate it

On Sloptimization

by Steve Coy

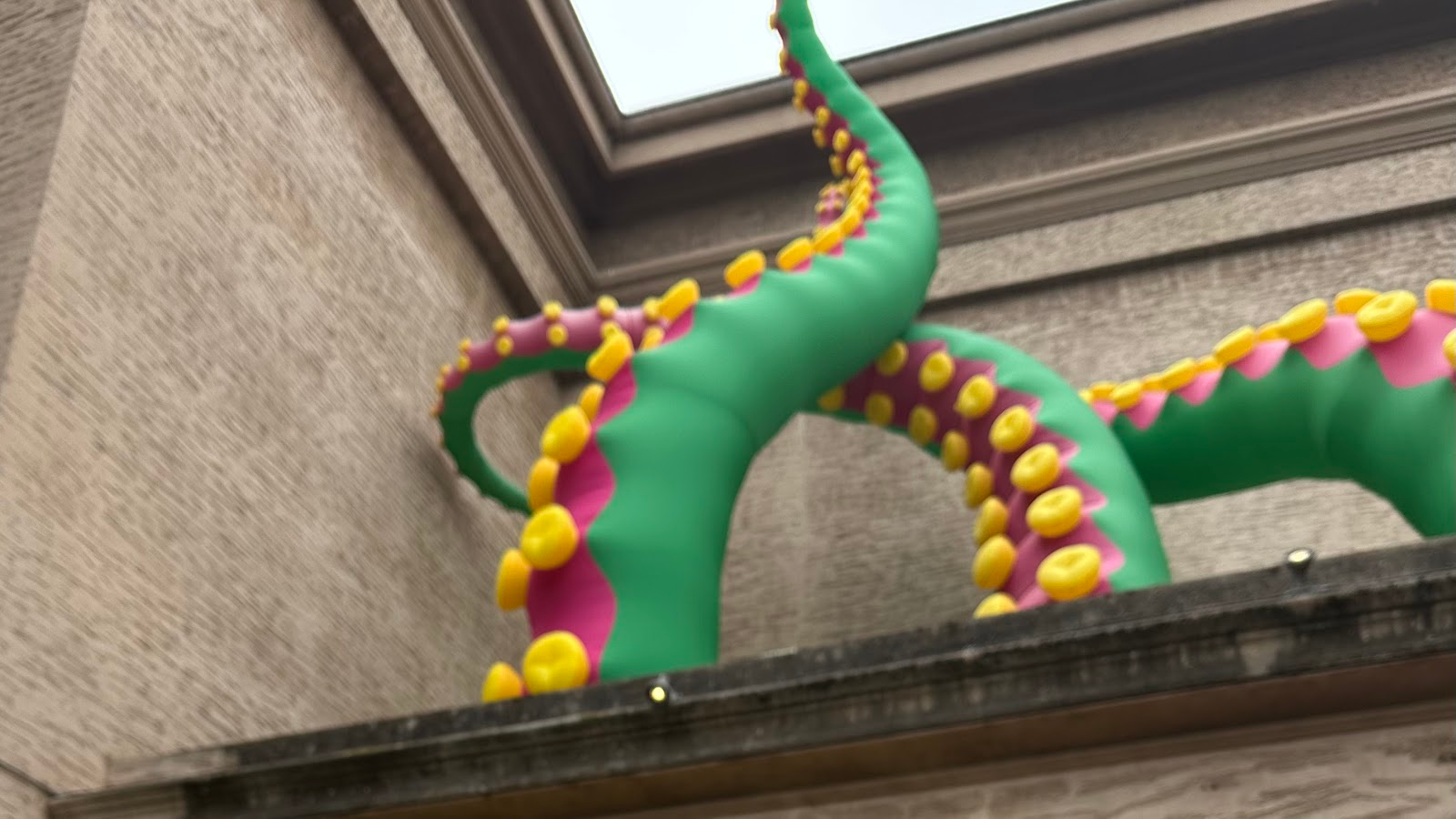

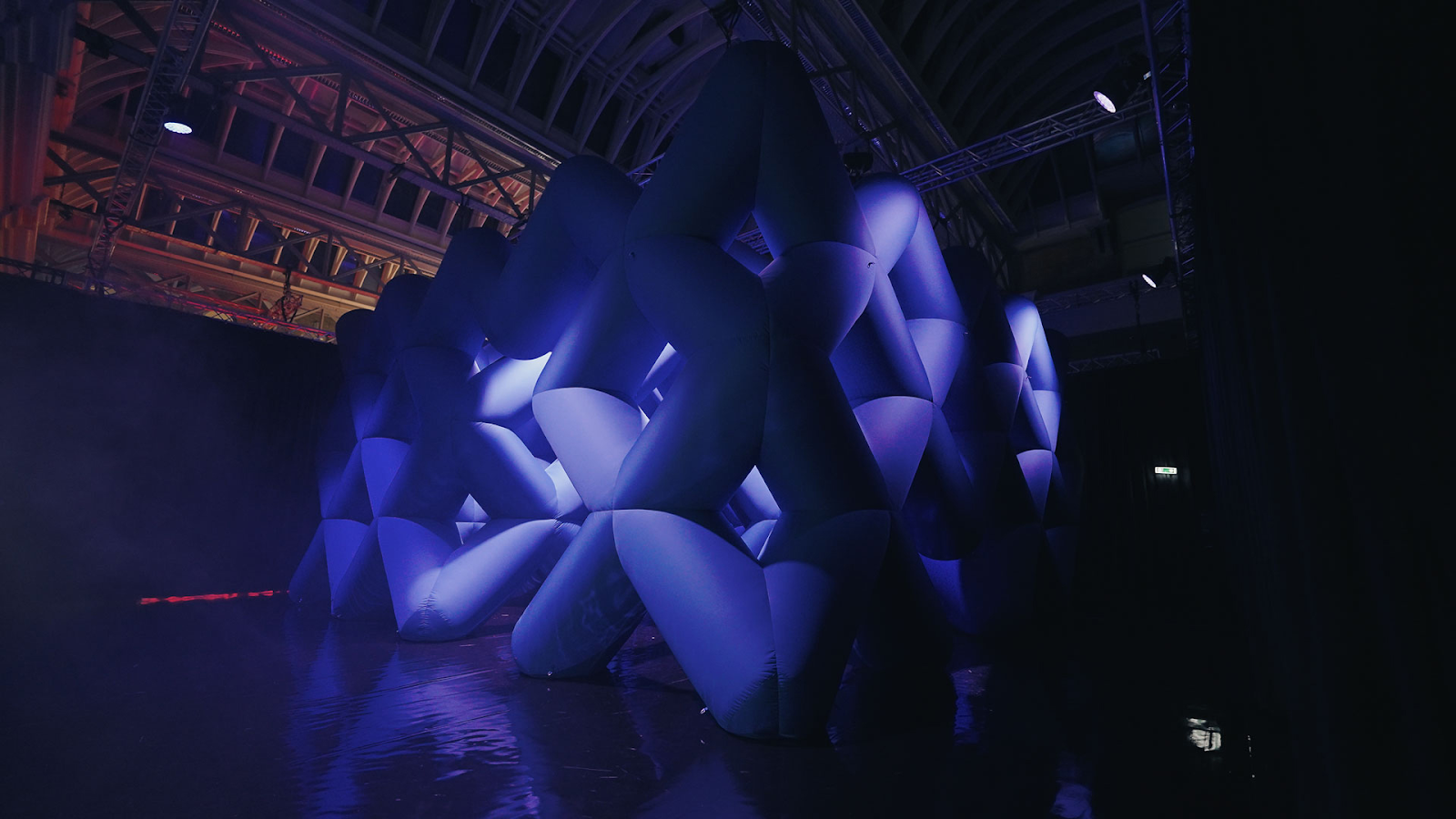

The limbs of a kraken writhe over the entrance to a Romanesque ruin. Stretching at the fog that once gave cover to the Zodiac, they might portend a new epidemic of chthonic madness engulfing America’s premiere imagined urban hellscape. Except they’re pink and yellow and green and they’re here to tell you everything is going to be okay.

The tentacles atop San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts belong to Emotionair, a traveling exhibition of inflatable art put on by The Balloon Museum, a certifiable global phenomenon and subsidiary of multinational experiential event consortium Lux Entertainment S.p.A. Think The Museum of Ice Cream, but with (more) bubbles. Even if you’ve never shelled out for one of these immersive experiences, you’ve seen them: brightly colored photo-op tableaux constructed at massive scale to be captured and cropped for a phone screen.

If the amused throngs of mostly childless urbanite attendees are any indication, Emotionair is a fine way to spend an hour and $30 ($50 on weekends). And there’s nothing novel or particularly perfidious about conspicuous aesthetic tourism. But those kawaii appendages point toward a uniquely modern hollowing-out of the pleasure and leisure spheres. Mediums like art, film, and food once reliably promised occasional enrichment via the unpredictable, even uncomfortable thrill of discovering something new. Lux Entertainment and its cohort have something else on offer: a familiar, frictionless, reduced-agency complement to the tech-enabled capital and labor-market forces grinding us all into dust.

It’s all delight, no surprise. The things we get to do for fun are now fully sloptimized.

The first exhibit at Emotionair San Francisco is “Cube Abyss,” a four story-high inflatable lattice inspired, in artist Cyril Lancelin’s telling, by “anxiety linked to the unknown.” Put less artily, it’s a maze-like adult bounce house (bouncing discouraged) with a white line on the floor to shepherd you through the mystery and on to the next attraction. Whatever the merits of its artistic intent, it’s a perfect, and perfectly titled, introduction to the three foundational principles of sloptimization.

Infantilization

In 2007’s seminal millennial comedy Knocked Up, a disaffected Paul Rudd sighs, “I wish I loved anything as much as my kids love bubbles.” Emotionair has a solution, and it’s mostly soap and water. A sign by the exit lays bare their timewarp gambit: “We hope you reconnected with a special part of yourself today.” I did! Pity the snack bar doesn’t sell Uncrustables.

As deployed by Hollywood IP retreads and bacchanalian milkshake outfits, nostalgia is a powerful tactic for transporting the consumer to a state of comfort and reduced anxiety. But revisiting the past is not inherently sloptastic–even Disney’s Freakier Friday builds upon and mildly interrogates its 2003 predecessor. The truly sloptimized experience must also commit to a few other requirements.

Conflict avoidance

Bubbles and bounce houses are none too subtle illustrations of how sloptimization sands away the consumer journey’s jagged edges. Streamlined, mobile-first customer flow is table stakes; once-scrappy DIY outfit Meow Wolf has a snazzy app to accompany its investor-funded expansion. The sloptimized “innovation” is that this reduced friction, this halfhearted ease, now shapes the content of the experience, too.

To wit, Emotionair’s centerpiece, a football field-sized ball pit. Signs, and thankless proctors with megaphones, admonish guests against jumping into, throwing, or lingering too long amidst the balls. Instead, visitors are instructed to pay attention to “The Performance,” a video display of AI-generated squirmy, cuddly, and fluffy imagery projected on wraparound LED screens and a sphere suspended over the center of the pit. Two neutered, enraptured minutes later, it’s on to the next room–the exhibit, we’re told, is woefully behind schedule today.

Set against the context of burnout, ennui, and decision fatigue, the removal of choice and agency may feel like liberation to the placid grownups in the ball pit: Sure, I’ll pay $30-50 to be ordered around a McDonald’s Playplace for an hour, sign me up. Even urbane sophisticates and refined aesthetes might opt for the soothing, low-stakes gratification of a corporate origin docudrama on Hulu and DoorDashed poké bowl now and then. What makes sloptimization such a loathsome bargain is its necessary embrace of Antisocialism.

Antisocialism

It’s crucial and purposeful that many sloptimized experiences have appropriated the label “museum,” which grants venture-funded brands a veneer of respectability while shearing away the term’s thornier connotations, like preservation, education, criticism, and disinterest in profit. To investors, these spaces promise the cash flow of a real civic institution without the pesky grant writing or social responsibility.

The privatization of large-scale cultural spaces also reflects a related rising tide of anti-intellectualism, wherein even experiences built on “real” art decontextualize and corrupt their source material to the point of meaninglessness. Witness the commodification of Van Gogh’s (public domain) oeuvre for immersive experiences, or the Las Vegas Sphere’s accursed AI-”enhanced” interpretation of The Wizard of Oz.

If this criticism smacks of stodgy revanchism, well, sorry, art must retain some engagement with the circumstances of its creation, and with broader institutions like cultural criticism or (actual) museums. Otherwise, it’s not Art–it’s Content. And that’s fine, or it would be, if Emotionair and the like didn’t insist on calling themselves art exhibitions. The boundary between linguistic malleability and meaninglessness may be vanishing, but it ain’t gone yet.

We can now narrow in on a working definition of sloptimization: the capital-driven explosion of creatively compromised diversions that sandblast emotional texture to a dull sheen. In other words, mids.

So what? Lux Entertainment S.p.A. didn’t invent mass-market pablum. Netflix Chief Content Officer Bela Bejaria may loudly and proudly proclaim her “non-intellectual,” “gourmet cheeseburger” bona fides in The New Yorker, but she’s not the first studio exec to simply give audiences what they want. (It’s no surprise that her company recently launched its own popular immersive experience and plans to build more.) Why do today’s middlebrow experiences merit their own special portmanteau?

We may find an answer in another recently coined, linguistically similar phenomenon: Cory Doctorow’s principle of enshittification, the intentional, capital-driven degradation of quality endemic to online services like Google and Facebook. It’s no longer confined to free-to-use platforms. “Enshittification is coming for absolutely everything,” warns one popular post on Reddit, one of the last remaining internet bulwarks against enshittification. Try ordering food at McDonald’s, and you’ll encounter an app-enabled, gamified, and dehumanizing kiosk. All across the Bay, recycling your empties has been similarly hijacked.

It’s not just that enshittification has come for our leisure time, infecting the activities that are supposed to provide a respite from the ache of modernity. Capital’s gonna capital, pushing us toward the transportive comfort of watered-down entertainments that run on the same rails as all the other slop.

The problem is that it’s working. Life under tech-dominated capitalism is so degrading, so exhausting, that more effortful diversions start to feel that way, too. “I’m not paying you to think” is something an asshole boss might say; it’s also what you tell Netflix with your subscription dollars. Why seek out a rep screening of The Cranes Are Flying when for a few dollars more I can let out my frustrations kicking around six-foot balloons? To be fair, I can’t even say there was nothing interesting about standing alone in a basketball court-sized enclosure and beholding this Orb.

Sloptimization may kick out a banger or two. But like other seemingly hegemonic tech-enabled forces, it’s not an immutable fact of life. There are worthy avenues for intellectual stimulation and creative integrity—smash that Subscribe button to get a year’s worth of Hell World for just over the cost of one hour of Orb Time! A post-postmodern reinterpretation of the public cultural space may feel as wildly out of reach as universal basic income, but you do what you can to keep your own face out of the slop trough.

Then again, a democratic reclamation of immersive experiences isn’t without precedent. The Palace of Fine Arts is, and always has been, an experiential venue. Where once it housed art exhibitions, it now hosts concerts, an escape room, and surge-priced multimedia attractions. But as originally built, it was the slop installation of its day, a disposable plaster-and-burlap shantytown intended to stand only for the duration of the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. By the mid-1960s, it was every bit the ancient ruin it was modeled on, until a group of civic-minded preservationists marshaled public will (and funding) to rebuild it. Today, couples take wedding photos at its lagoon, artists hawk watercolors of its trademark rotunda, and kids run around feeding its waterfowl stuff they probably shouldn’t. It’s always there, always beautiful, and always free.

Steve Coy is a Millennial Experience Lover living in the Bay Area and posting on Bluesky @mcleemz.bky.social

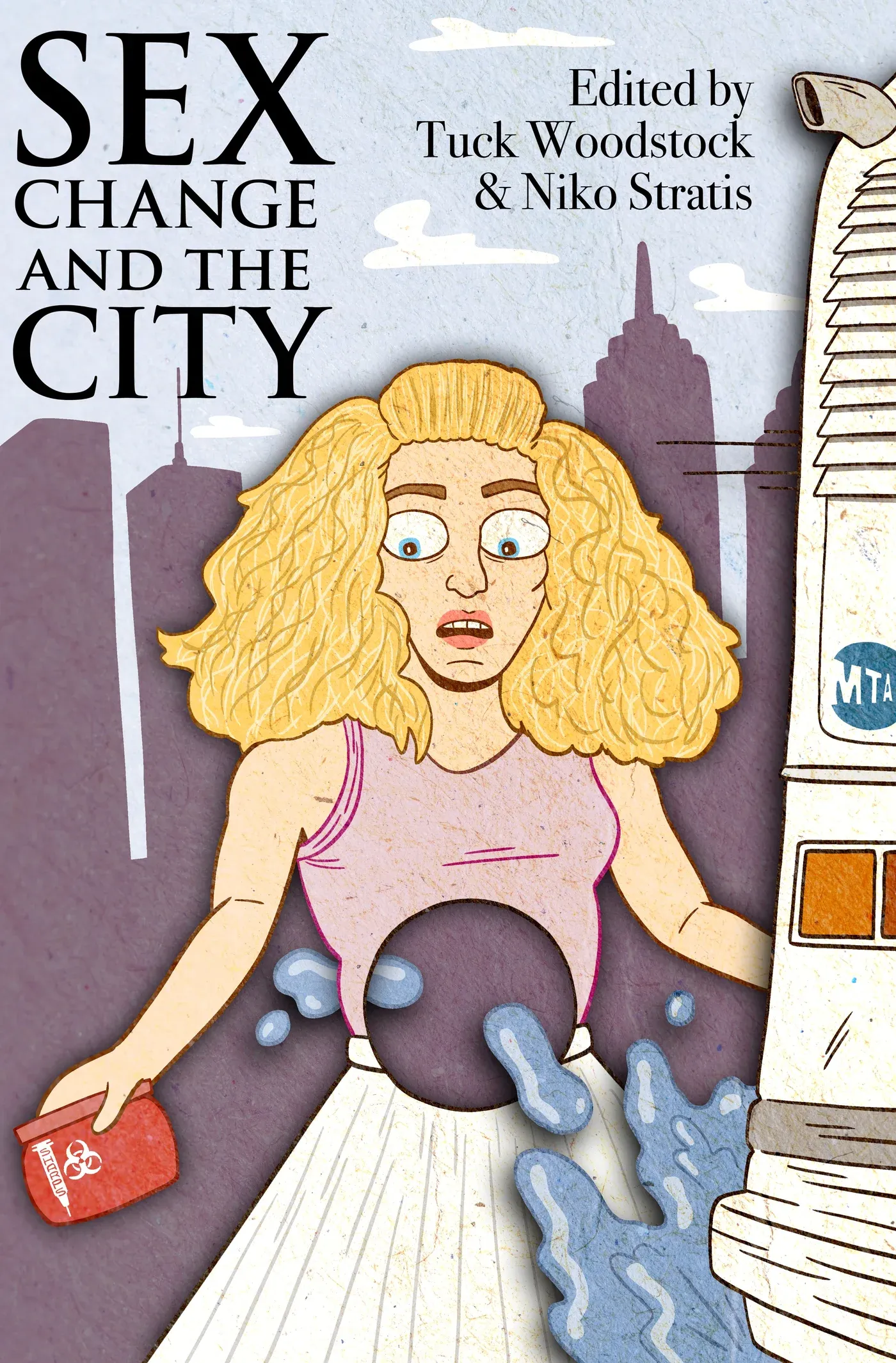

Everything doesn't have to be awful all the time. Things can still be fun. For example this new anthology edited by pals Niko Stratis and Tuck Woodstock featuring dozens of great LGBTQ+ writers on the HBO classic series Sex and the City.

Tuck explains a little more about the book:

Sometime in 2023, back when Twitter existed, Niko Stratis and I began joke-tweeting about making an all-trans zine of Fast & Furious-inspired content. By the end of the year, our joke had escalated into a 160-page anthology titled 2 Trans 2 Furious, which somehow won a prestigious literary award despite mostly existing as an excuse for our friend Mattie Lubchansky to draw Vin Diesel animorphing into a car.

Elated by our success in the niche field of Trans Shitpost Publishing, Niko and I promptly founded Girl Dad Press, a “trans press for all freaks,” and began working on our second collection: Sex Change and the City. This all-queer, mostly-trans anthology includes thoughtful meditations on the shame of secret relationships, the grief of losing a family member, the confusion of young adulthood, and the rage of middle age—as well as comics, poetry, a role-playing game, something called Mr. Big’s Phalloplasty Emporium, and multiple pieces of Steve/Aidan slashfic.

When describing the book, I often emphasize the sillier moments: Mad Libs, self-insert fanfic, a photo of an ass tattoo, an A Christmas Carol/Sex and the City mashup starring Caitlyn Jenner. But in truth, I’m impressed by the vulnerability, growth, and heartbreak that many contributors wove into their essays about a 25-minute sex comedy. A prime example of this is Georgia Mills’ sharp, feverish essay Girl, Haunted, which has indeed haunted me since I first read it a year ago. I hope it haunts you as well. –Tuck Woodstock

Order the book in the Girl Dad shop and get 10% off with the code HELL.

Read a recent Hell World interview with Mattie Lubchansky here.

And one with Niko Stratis here.

Girl, Haunted

by Georgia Mills

In the Sex and the City episode “My Motherboard, Myself” (S4E8), Carrie’s computer breaks and Miranda’s mother dies.

Each of the women respond to Miranda’s mother’s death differently: Carrie lashes out, Charlotte sends flowers, and Samantha shuts down. When Carrie tearfully breaks the news over breakfast, we see Samantha go someplace else. She dissociates; her eyes unfocus. During sex, she loses her orgasm (“in the cab?” Carrie chides later), and in Samantha’s distress we see something deeper: her fear of death, under her sex-fuelled zest for life.

Rewatching Sex and the City, I’ve been thinking about the work that it takes to become the person you want to be. Throughout the show, Samantha occasionally shares details about her life before moving to New York: serving dilly bars at Dairy Queen when she was fifteen; getting an abortion alone in college; how her mother was saddled with “three kids and a drunk husband” by the time she was Samantha’s age.

Samantha’s past is buried underneath her glamorous and professional exterior, whereas Carrie lives as though she’s still the younger version of herself: the Connecticut teen who dreamed of moving to the city. She parties until dawn and loses track of time, romanticizing New York and Mr. Big, coffee and cigarettes. Time and time again, Carrie is rescued from her mess—breakups and financial issues and fights with friends—via magical thinking and impossible HBO luck. “In real life, the city would eat her up,” my friend said as we sat outside a coffee shop in sweats on a Sunday, dreading the workweek.

I feel embarrassed when I act like Carrie, giving my inner teenager access to my bank account and body, letting her drive the car towards shiny lights and buzzy thrills. Waking up hungover at 23 from tequila, and the recollection of what she drove me to, the mortification that comes the morning after crying in the back of an Uber for reasons only she knows, I don’t (ughgod), holding onto the side door and seeing stars, stumbling up the stairs home in a tangle of jangling keys and earbuds and heel straps and text messages, laying on my back on the cold linoleum floor, eyes closed, breathing. I never really find the feeling that I’m looking for on a restless night out. I’m seeking to soothe pent-up frustrations; to exorcise the banal demons (“nobody talks about backing up; my computer died”); to distract from the fact that being a writer with a column is an unreal dream, that it takes two jobs and weekly therapy and expensive chemical face wash to “keep it together.”

The stable life that Samantha has built for herself allows her to live comfortably, and she works hard to take care of herself. She knows how to play the game to get what she wants. She owns an eponymous PR agency and a loft in the Meatpacking district. (“See, New York? We have it all,” she toasts over a bottle of champagne upon moving in.) When Carrie needs $30,000 to buy her apartment because her building goes co-op, Samantha offers to loan her half the money.

Over martinis and chocolate cake with the girls, Samantha declares that she’s never cried at work. Carrie says that she cried to her editor when she missed a deadline—she claimed to be having problems at home, but in reality, she was sunning in the Hamptons.

“That makes the rest of us look bad,” Miranda scoffs.

“Oh boohoo, it was 80 degrees and sunny,” Carrie says, shoveling cake into her mouth.

Carrie obsessively labors over her relationships, feelings, and memories. She splays out on her bed, writing about her experiences, reliving moments alone in her room. Her life is still my fantasy. It’s easier, in that it takes less effort, to let yourself be driven by your emotions, without doing the work to resist your impulses. (Sending a stream of texts in an anxious moment; staying out too late.) But indulging in this way of being doesn’t feel cute or fun anymore—letting myself live like Carrie, in the real world, creates a vicious cycle of regret. Chaos and drama, forgetting bill payments and birthdays.

Through Carrie’s neurotic personality, I see a baby woman searching for a magical concept of love in a princess dreamworld. This is why, when her sense of reality is shattered—by a broken computer, a broken heart—she wants time to stand still for her sadness.

Five more minutes, something I’ve always said. I just want five more minutes.

Carrie’s constant rumination contrasts Samantha’s fear of slowing down. Samantha lies about her age; she gets plastic surgery. She loves work and sex and parties and being present in the moment. She seems to have a pervasive awareness of time passing, and a deep fear of looking in the rearview mirror, of pulling over. When Charlotte says that she wants to quit her job to have a baby and volunteer at her husband’s hospital, Samantha tells her to be “damn sure before you get off the Ferris wheel, because the women waiting to get on are 22, perky, and ruthless.” Imparting this wisdom is Samantha’s way of mothering her friends. Underneath her advice is her fear of powerlessness, of getting stuck in a mediocre life. “You have to grab 35 by the balls,” she says on Carrie’s 35th birthday.

Miranda’s mother’s death comes suddenly and unexpectedly, with lots of realistic practicalities attached. The day of the funeral, while Miranda is shopping for a “shitty black dress,” a matronly saleswoman informs her, unsolicited, that she’s been buying the wrong bra size.

“I think I know! What’s best, for me!” Miranda snaps at the woman now tugging expertly on her bra straps. Then, after a pause, she blurts out an explanation: “I’m sorry. My mother just died, and—”

The saleswoman’s face folds knowingly as she wordlessly embraces Miranda, who melts into her shoulder. Through the screen: the stillness of a moment that feels good and heavy and long, like a warm nap. Close your eyes, stay forever (five more minutes).

At the funeral, while Charlotte and Carrie say all of the right things, Samantha can’t summon the words to acknowledge the death at all, awkwardly complimenting Miranda and looking around uncomfortably in her seat. During the service, she breaks, locking eyes with Miranda across the pews, mouthing “I’m sorry” as she begins to inconsolably sob.

Samantha’s emotional turmoil in “My Motherboard, Myself” reminds me of a previous episode, “All or Nothing” (S3E10). Sam gets the flu and insists that Carrie come over to make her mother’s “cure-all” childhood concoction: Fanta and cough syrup blended over ice. In her feverish state, Samantha cries over not having a boyfriend to fix her curtain rod. (“We’re all alone, Carrie.”) She’s crying for longings that she didn’t know she felt: for what her mother wasn’t able to give her—a stable home and a solid foundation—and the particular sadness that comes from craving a deep comfort that you’ve never had, as an adult in your own apartment.

Later, when she’s feeling better, Samantha brushes her crying jag off with a joke about how sick she was, her voice as taut as an old movie star’s. I wonder if that’s what it takes for her to be the woman she wants to be every day—her sense of reservation, a lack of emotion. To not be like her mother.

After her emotional exorcism in church, Samantha comes during sex.

“You have to confront the ghost, acknowledge its presence, then release it,” she says earlier in the season, when Miranda thinks that her apartment is haunted. “Everybody knows that.”

Georgia Mills is a writer based in Toronto, ON. More importantly, she’s a Carrie sun, Charlotte moon, and Enid rising (IYKYK).

This story appears in my new book We Had It Coming – available now.

You are in a museum

They drove up to Salem to be somewhere different for a little while. Anywhere different.

Salem was usually a magical place for them but not because of the whole mess every October. She could take or leave the Salem of it all so it was refreshing being there before the throngs of tourists who would be arriving shortly.

They naturally considered themselves the good kind of tourist.

The magic comes when you’re not expecting it they both knew.

Stumble onto a random cobblestone street and there before you will stretch a block that you could convince yourself had remained unchanged for hundreds of years. That this is still what the world is. You might believe albeit briefly that you were standing there in 1700 and then you’d crumble into dust and blow away on the wind because the life expectancy back then was like 38. Which happened to be what they were.

This can happen sometimes in Boston too but so much more rarely now.

They walked around the main commercial area and it was bright and beautiful out when they turned left down a small street that the sun couldn’t find and she swore to God that all of the leaves on the trees looked like they had just fallen moments ago and were resting dead on the ground. That the temperature had dropped twenty degrees right then and there in August.

Down at the end of the block there was a squat brick building that must have been a few hundred years old. She thought whatever had once gone on inside of there was none of her business.

Well this can’t be normal she thought with the leaves crunching underfoot and so they turned heel and shortly thereafter all of that sense of foreboding was deflated after walking by about fifty different shops selling witch t-shirts and witch tchotchkes.

They got a lot of witch bullshit out already she said. I’m not sure what else I was expecting she said.

She thought about how awful it must have been living under the thumb of a draconian authority who ruled with suspicion and revenge as their entire animating principles.

Next walking into the Peabody Essex Museum. There was an exhibit of South Asian art focusing on the effects of British occupation on Indian self representation and one on maritime art from around the world with a focus on Salem’s seafaring history. He thought looking at all the paintings and objects more than anything that being on a boat any time before relatively recently in history must have fucking sucked. Getting violently sick and then probably drowning. All for some other guy’s profit.

Pretty much sucks now too for that matter.

There had been a shooting recently so she felt on edge being in a crowded public space.

Seven members of a family in Ohio including a nine year old boy were shot in the head execution style. The shooter had become irate when the family asked him to stop firing off his AR-15 recreationally in his backyard so he killed most of them. Three of the other children survived. They were found covered in the blood of their mothers who were both killed while laying on top of them. Throwing their bodies in front of the bullets.

They safely hid a two month old under a pile of clothes.

Do you ever think about a shooting she asked.

By which she meant do you have a little pilot light of anxiety always burning somewhere inside. A little seed of dormant foreboding. Something strapped to your back like a heavy satchel.

I think about it more often in the aftermath of a bad one he said. I feel a bit more on edge in large public gatherings or in malls or wherever.

When do you ever go to the mall?

The proverbial mall. You know what I mean. But they happen so frequently now the reprieves in between don't last very long.

They were saying on my phone last night that you have to be prepared at all times like a soldier. Be prepared to kill anyone you see she said.

Fuck that he said. I refuse to think like that.

Sorry sorry he said speaking more quietly now. Remembering where he was.

I am aware of my surroundings he said. I don’t take any unnecessary risks or instigate any stupid confrontations. But I will not give in to that way of thinking.

I look for exits more frequently now she said. It's just like looking both ways before I cross the street. It's automatic. I read someone say that somewhere. A habitual tensing.

They were quiet for a while after that and wandered into a large hangar-like room for what was supposed to be a show-stopper of a piece. It was called All the Flowers Are for Me and it was a giant floating cube of sorts constructed so the light from within reflected all over the walls in precise and ornate floral patterns.

It was the type of cube where you’re not sure if it’s going to impart some kind of ancient wisdom as you gaze into it or if it’s going to absorb you into its horrible eternal gleaming she thought. Maybe both.

Mostly it was the kind of piece that people want to take Instagrams of which she did.

She shuddered suddenly thinking of three red throbbing pillars off the coast.

Moving on to an exhibit called Down to the Bone. Photographs of polar bears scavenging the remains of dead whales in an Inupiat village in Alaska. How tiny the giant bears looked climbing along the stripped-clean bones of the leviathans. She thought the skeletons seemed like they must have been arranged just so by the artist but then figured it’s more likely they fell together like that in an accidentally beautiful deathly architecture.

“We have lots of bears here in Kaktovik because they have no place to go,” a quote from a hunter read on the text card.

“The bears here are climate refugees. Soon we will be climate refugees too.”

He stood looking on dumbly over her shoulder.

I don’t know he said.

What?

I don’t know if I’m any good at going to museums anymore. I try but I just don’t really get uhh transported anywhere he said. Not like I do just standing on an old street. Like the one from earlier he said.

Which street she said.

I don’t know.

He thought that museums necessarily strip away a few of our senses. Nothing smells like anything and you usually can't touch or thankfully taste anything so that just leaves the looking and sometimes the listening.

With so much quiet it's hard for me to block out the part of my brain that’s operating in the background going you are in a museum.

You are in a museum and it is time to be moved by art.

They left soon after and rode an elevator up to a hotel rooftop bar that was just fine. Perfectly ok. Everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves drinking their frozen strawberry habanero margaritas and eating their roasted shrimp tacos with jack cheese and corn salsa and poblano crema.

At the bar the staff had a flyswatter out and they were using it to try to kill some bees that had found their way all the way up there.

I know this is probably stupid but it had never occurred to me that bees could fly up this high into the sky he said. I had always assumed they operated on a relatively low to the ground kind of deal. Occasionally flew up into a tree at the end of the work day.

I think this is probably about as high up as they can make it she said.

Five stories up he said. All the way into the sky and we’re all acting like everything is normal? It occurred to him that he didn’t know anything about nature or the world at all. Who designed all of this shit? Who made it all just so he thought and then thwack they got one. Then another.

Thwack. Thwack. Thwack. Thwack.

The bartender was on a hitting streak now. The rest of the staff and all the day drinkers were cheering him on. He couldn’t miss. He couldn’t stop now if he wanted to.

The elevator dinged and someone was striding out of it now with purpose. They both turned on their stools. It was just some guy. It was no one at all.

My new book is shipping out this week. Order it now!

Come hang out in NYC on November 12 and in Boston on November 8 at the Sinclair. More details on that one to come.