Instead it all just goes in the one direction

That’s pretty much one of the main things men have to be fucked up about

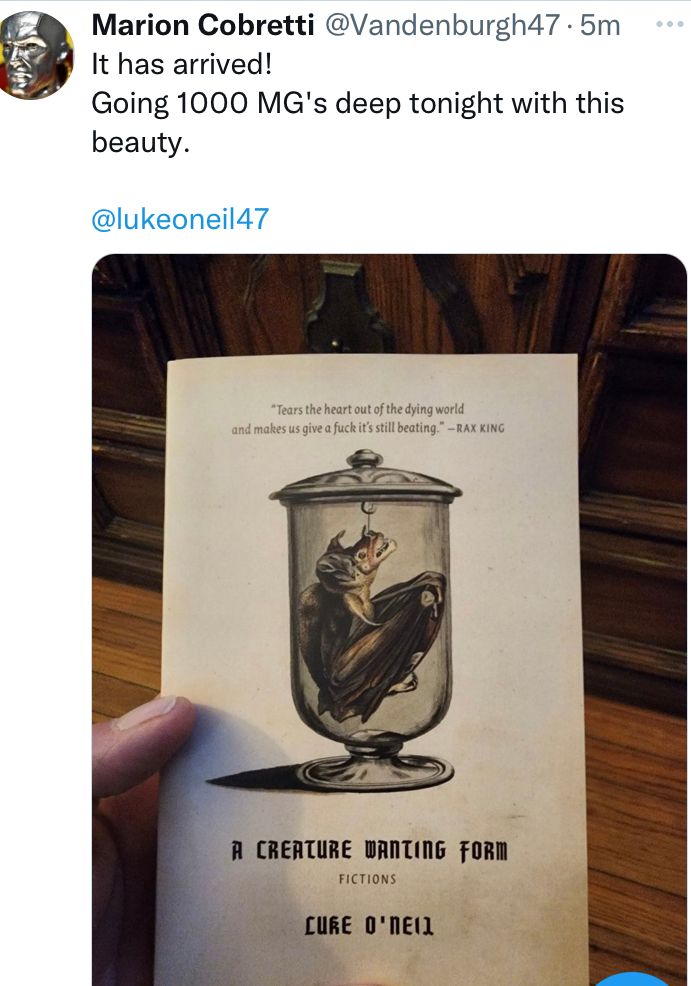

There is a part of me that wants to say sorry for plugging the book so much all the time but on the other hand I do not care about anything else in the world besides its hypothetical warm reception so you can see my dilemma here. That and being skinny. And that's not going so great lately either.

(Follow me on Bluesky here by the way. Or on Instagram here for that matter. It's gonna be sad when it's finally and at long last time for me to leave Twitter. I was really counting on my following there to come through for me someday when I need to fundraise for a medical emergency.)

Peddling your book sucks so bad!! Humiliating shit. Going around with your little hat in your hand. Please sir... one crumb of validation. My family is unwell. You should just be able to write it then walk away in slow motion as it explodes behind you.

It's like I always say being a writer is the hardest job in the world. Harder than teacher or nurse or coal miner or shit-shoveler. And every time you do not read my book you are shooting one (1) bullet into my brain. You don't want to do that do you?

Same deal again as before today. One year of Hell World at full price and I'll send you an autographed copy of the book as a little sweetener. I've only got seven left so act fast. Medium fast more likely.

It's Father's Day today so congratulations or I'm very sorry about that. A happy day to all the fathers out there but specifically to Bobby O'Neil.

Here's a story from the book about dead fathers (more or less). One of the main things a story about a father can be about is him being dead or an asshole. Often times both!

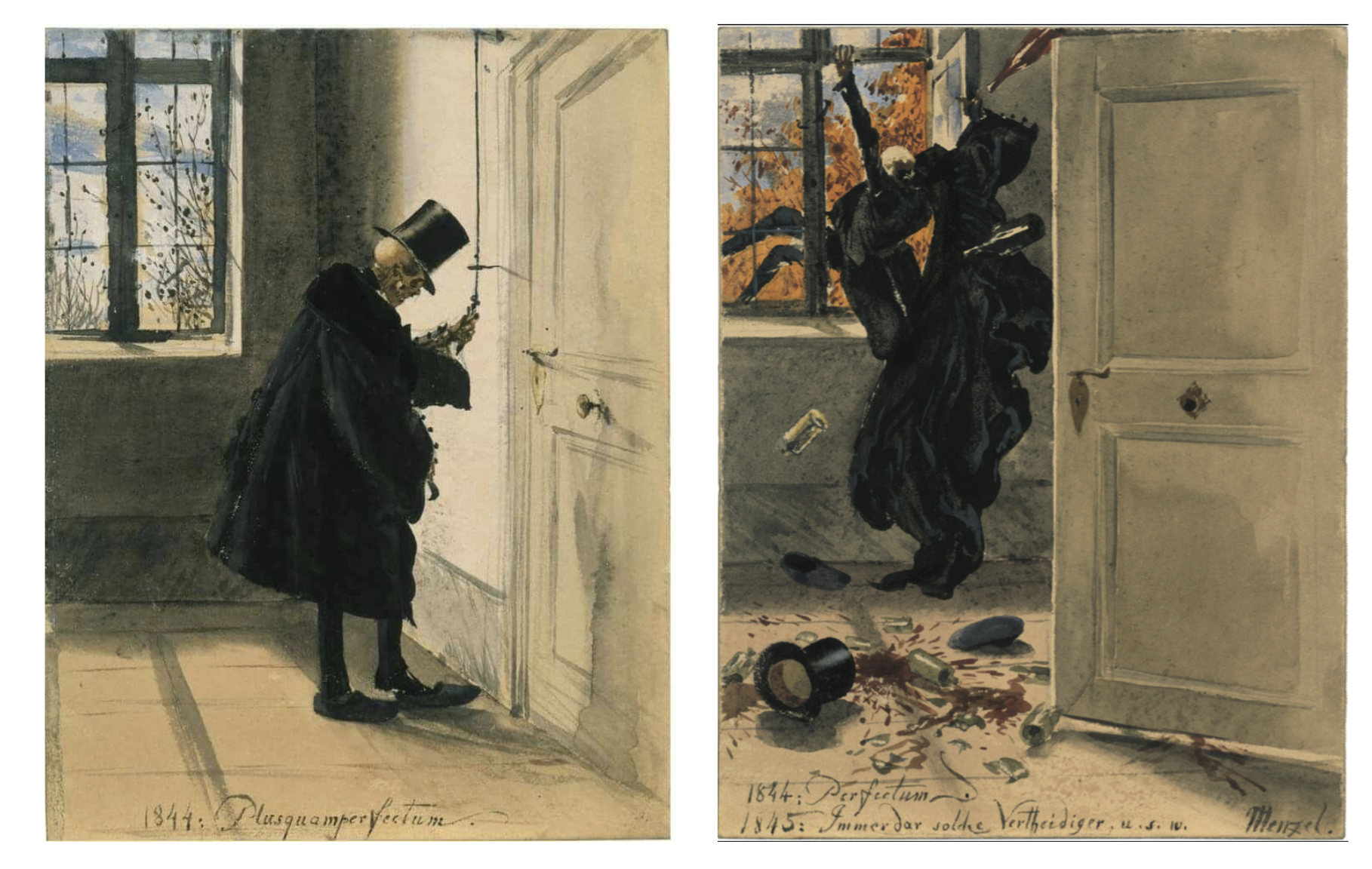

The Uninvited Guest parts 1 & 2

In the first painting the gentleman is tastefully appointed in a large black overcoat and a top hat. His head is dipped out of reverence for his solemn duties or perhaps to disguise himself as he pulls the chain outside of the apartment door to announce his presence.

He’s in the process of removing his shoes before entering as a sign of respect and in the open window behind him the trees seem in first bloom.

Despite it all he appears to be smiling but it’s rather the unavoidable showing of the teeth. It’s impossible for a skeleton to frown.

They were staring at the little information card next to it like people do at museums as if it would divulge something that was being kept hidden from them in the artwork itself.

The artist inscribed “1844: Plusquamperfectum” along the bottom of the canvas which very roughly means more than enough time has transpired.

Neither of them knew that it meant that by any stretch of the imagination but that’s what it meant roughly.

Is that Latin?

I think so.

What do you make of it she asked and he said I don’t know it makes me think about the war.

When you say that type of thing no one wants to follow up you win a get out of talking free card for a bit but standing there before the painting more than anything he was thinking about how much longer it would be before they could go get lunch.

It was an anniversary of a day he didn’t like to think about but his phone memories made him anyhow. It was a photo of a power plant or factory of some kind looming over the water of Buzzards Bay just at the top of Cape Cod. It’s gray and raining in the photo and there’s a bike path with brightly painted lines curving off out of frame as if to suggest infinity and when he took it the day they clumped some wet ashes onto the mossy rocks down there he thought it was this real emotionally evocative and moody tableau like it encapsulated Death Itself as a concept but in retrospect that didn’t really track because the yellow arrows on the path are pointing both this way and that and that’s not how dying or time works. Instead it all just goes in the one direction.

He often felt guilty because most of the stories he told about his father were about him either being sick or dying but for the past twenty years of his life that’s pretty much all he ever saw him doing and in the first twenty they didn’t have phones to offload memories onto for safekeeping.

He sometimes felt sheepish too because what a silly cliché it was to be a fully grown man and still be fucked up about your dead father but that’s pretty much one of the main things men have to be fucked up about besides war so give him a break he thought. He didn’t invent psychology.

It’s very hard to spread a person’s ashes without feeling as if you’re doing it in an artful and mannered way. It feels too cinematic and performative even if you are only performing for an audience of ex-wives and conflicted children standing there in their gas station rain ponchos.

The night before in bed she had reread “The Sound of Her Wings” a comic book tale which was the first appearance of the personification of Death in the Sandman universe and is pretty much a perfect short story as far as she was concerned. In one part Death asks a violin-playing old man if he knows who she is and he goes No! Not yet! Please? and then a second later he’s like Ah . . . well . . . and he accepts it like.

What can be done you know?

After that Death nestles a baby in a crib to her breast and the baby too is like Is that all there was? Is that all I get? and she says Yes I’m afraid so.

Later on in another issue Death talks to a different old guy and when they meet he asks her if he lived an especially long life and she goes You lived what anybody gets. You got a lifetime. No more. No less. You got a lifetime.

The whole idea of the series is about gods and their assorted colleagues who begin as dreams and then become manifest in the corporeal world the one the comic book humans inhabit and they remain real there as long as anyone believes in them and then someday when no one remembers them anymore they disappear forever which is basically what happens to all of us too give or take some of the grandeur and villainy.

She tried to get him to read it so they’d have a shared interest but he never read anything she or anyone asked him to.

I read enough when I was down there he’d say.

She’d talked to her mother earlier that day and she said she finally broke down and got hearing aids after years of her children asking her to. Her mother said she cried when she first put them in and she very easily understood why her mother would cry about that she wanted to cry about it too.

She grieved for her preemptively but she also thought it will be nice for all of the siblings to not have to repeat themselves three times whenever they tried to tell her anything.

Ma . . . Maaa!

In that disgusting accent she knew they all had.

For some reason he didn’t understand he was trying to remember if he knew what his father’s legs looked like. He knew he must have seen them on occasion at the lake in the stolen forest when they’d go camping but he couldn’t picture them. He could picture his tattooed forearms however because he remembered stroking them gently as he was dying.

Years ago a thing people often used to say was how do you think those tattoos are going to look when you’re old and he never paid attention to that but after all of the time in the hospital he knew now how they would look which was a profane joke. Not the inking of the tattoo itself but the decaying.

The next painting over was the second in the series. In it the dapper skeleton is jumping out of the window in a hurry and there are wine bottles bursting all over the walls as if the person inside the apartment was really going after his ass. It was funny like in old cartoons when the cartoon wife would get the broom or frying pan out and chase the cartoon husband around. The guy’s little cartoon hat flying off.

It’s not so much someone being gone that’s the thing he thought and she was touching his arm and reading his mind now in the way a person who sincerely loves you can do. It’s the having been made to watch people go so slowly.

This is why they invented the Irish Goodbye he thought.

Underneath the painting the artist had written “Perfectum” and then under that “Immerdar solche Vertheidiger” which roughly means always such defenders although that doesn’t sound right.

Is that German?

I think so.

Neither of them knew this of course.

It seems like it should mean never mind I gotta get out of here because the bone man looks like he’s scared out of his mind. Like he’s running for his life and he doesn’t even have one to hold onto. It doesn’t make any sense. What can the living possibly do to harm the dead besides forget them?

Did you read this one from the other day by Kevin Koczwara about struggling with being a father in the age of regular mass shootings?

Who can drop their kid off in America today and not fear the worst? Who can go to a mall or a concert or any place really without second guessing the decision? Who would bring a child into this world? Who would bring something so precious as a child into a place filled with hate and violence? My wife and I have. Two little kids — seven and four years old now — who weren’t alive for Sandy Hook or Columbine or Texas Tech or any of the hundreds of other mass shootings before they were born. But they’ve been around for enough mass murders that it feels like they’re possibly numb to it already.

Or maybe I just haven’t explained it well enough to them because I don’t know how.

Now let us look at some poems about fathers ok? Ok.

All My Pretty Ones

by Anne Sexton

Father, this year’s jinx rides us apart

where you followed our mother to her cold slumber;

a second shock boiling its stone to your heart,

leaving me here to shuffle and disencumber

you from the residence you could not afford:

a gold key, your half of a woolen mill,

twenty suits from Dunne’s, an English Ford,

the love and legal verbiage of another will,

boxes of pictures of people I do not know.

I touch their cardboard faces. They must go.

But the eyes, as thick as wood in this album,

hold me. I stop here, where a small boy

waits in a ruffled dress for someone to come ...

for this soldier who holds his bugle like a toy

or for this velvet lady who cannot smile.

Is this your father’s father, this commodore

in a mailman suit? My father, time meanwhile

has made it unimportant who you are looking for.

I’ll never know what these faces are all about.

I lock them into their book and throw them out.

This is the yellow scrapbook that you began

the year I was born; as crackling now and wrinkly

as tobacco leaves: clippings where Hoover outran

the Democrats, wiggling his dry finger at me

and Prohibition; news where the Hindenburg went

down and recent years where you went flush

on war. This year, solvent but sick, you meant

to marry that pretty widow in a one-month rush.

But before you had that second chance, I cried

on your fat shoulder. Three days later you died.

These are the snapshots of marriage, stopped in places.

Side by side at the rail toward Nassau now;

here, with the winner’s cup at the speedboat races,

here, in tails at the Cotillion, you take a bow,

here, by our kennel of dogs with their pink eyes,

running like show-bred pigs in their chain-link pen;

here, at the horseshow where my sister wins a prize;

and here, standing like a duke among groups of men.

Now I fold you down, my drunkard, my navigator,

my first lost keeper, to love or look at later.

I hold a five-year diary that my mother kept

for three years, telling all she does not say

of your alcoholic tendency. You overslept,

she writes. My God, father, each Christmas Day

with your blood, will I drink down your glass

of wine? The diary of your hurly-burly years

goes to my shelf to wait for my age to pass.

Only in this hoarded span will love persevere.

Whether you are pretty or not, I outlive you,

bend down my strange face to yours and forgive you.

My Father's Memorial Day

by Yehuda Amichai

On my father's memorial day

I went out to see his mates–

All those buried with him in one row,

His life's graduation class.

I already remember most of their names,

Like a parent collecting his little son

From school, all of his friends.

My father still loves me, and I

Love him always, so I don't weep.

But in order to do justice to this place

I have lit a weeping in my eyes

With the help of a nearby grave–

A child's. "Our little Yossy, who was

Four when he died."

My Papa’s Waltz

by Theodore Roethke

The whiskey on your breath

Could make a small boy dizzy;

But I hung on like death:

Such waltzing was not easy.

We romped until the pans

Slid from the kitchen shelf;

My mother’s countenance

Could not unfrown itself.

The hand that held my wrist

Was battered on one knuckle;

At every step you missed

My right ear scraped a buckle.

You beat time on my head

With a palm caked hard by dirt,

Then waltzed me off to bed

Still clinging to your shirt.

Those Winter Sundays

by Robert Hayden

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?

Youth

by James Wright

Strange bird,

His song remains secret.

He worked too hard to read books.

He never heard how Sherwood Anderson

Got out of it, and fled to Chicago, furious to free himself

From his hatred of factories.

My father toiled fifty years

At Hazel-Atlas Glass,

Caught among girders that smash the kneecaps

Of dumb honyaks.

Did he shudder with hatred in the cold shadow of grease?

Maybe. But my brother and I do know

He came home as quiet as the evening.

He will be getting dark, soon,

And loom through new snow.

I know his ghost will drift home

To the Ohio River, and sit down, alone,

Whittling a root.

He will say nothing.

The waters flow past, older, younger

Than he is, or I am.

Here are some other father-related pieces from the Hell World archives.

Closer to the end, just before he was to be transferred to hospice care, I remember shaving his beard. It was the most intimate exchange we ever had. He was about to be carried out his front door and brought by ambulance to a place in Providence where people like him end up, and he wanted to look dignified. By now his beard hair had turned into brittle white straw that fell heavy to the ground when cut. He was cancer personified, but I made him handsome again. I remember holding my breath while trimming his neckline because I was secretly disgusted. He was sleep deprived and stoned and his mouth was usually open at all times by that point, so I didn’t want to breathe in the disease when he exhaled. Of course, I understood intellectually that that’s not really how it all works, but being face to face with oblivion is naturally repulsive and makes you feel things you’re ashamed of later. Still, he was the one who taught me how to shave so returning the favor was a way of saying what we needed to say without saying it.

A surprising number of stories in this one about old t-shirts are dad-related.

This was my dad's 1997 Roger Clemens Toronto Blue Jays t-shirt. My dad died in 2016. I took care of him for the last 2 1/2 years of his life, and though the overall experience of doing so was transformative — it gave me a chance to work all my shit out with him before he died, which was a gift — the reality of it day to day was brutal. It's not just the dying slowly part, it's things like cleaning up literal shit from the floor when he fell out of bed and having to pick him up like a baby and carry him back to bed and listening to him cry because my brother wouldn't visit him for the last months of his life while confined to a home hospice bed.

My first experience with death was sitting in the morgue inside my dad’s house in Northwest Indiana—the funeral home—on one of the Saturdays he had custody. Because I was probably in kindergarten, he didn’t trust me to be alone, so instead he had me sit in a rickety, old, wooden chair that had an armrest affixed to it with duct tape—we were Polish, after all—and let me watch as he and his embalmer guy sucked the fluids out of a person and replaced them with a batch of chemicals. I think I was four or five years old. I’m not sure this was better than whatever I would have gotten up to on my own, but I think it says a lot about our familial dynamic.

In my dad’s minivan there was a cot with a gray cloth cover that was always there, just in case, while we were out, we had to stop and pick up a body, either from the local morgue or on a house call. Once after a Little League game my dad gave another kid a ride home and he absolutely freaked out that a dead body had once been reclining on the cot in our van. I remember not being able to understand why this was such an alien concept to him. While I can appreciate that not every eight-year-old has watched people be embalmed on a regular basis, the fact that death was so abjectly terrifying even in this most tangential context has always stuck with me.

My dad and I have a fractured relationship for a lot of reasons, but one of the major issues stems from a very simple place: he wanted me to take over the family business and I had zero interest in doing that.

My father was diagnosed in 2017, and after a bunch of surgeries and some touch and go months where everything was very uncertain, he gained back a lot of his strength and eventually improved into what you might call “chronic.” He had most of his colon and a lot of liver removed in 2018, so there was always something going on, but you got used to it. “Oh, Dad’s gotta go get a CT, something is doing whatever.” Somebody asked me what changed the most when he was diagnosed and I just said that you say “I love you” a lot more because you want that to be the last thing you say to someone when you’re aware everything you say could be the last thing.

The fifth time I went to watch my father die was the one that finally took.

He'd been in and out of hospitals, and hospice, and nursing homes for so many years. He'd clawed his way out of so many comas. We all assumed up until the final moments that this time would be no different. In fact, I still half-expect to get a phone call from him today, his tobacco-ravaged voice asking me to call him back, like so many of the voicemails he left me over the past year or two. He was only 61, but a lifetime of dogged, determined substance abuse and enough related ailments had finally conspired to finish the job he had started at a young age.

I can no longer call my father on the phone but that was true for most of my life anyway. Perhaps I should have done so more often. Perhaps he should have. Every text I have now is a glaring reminder that neither of us bothered to. I feel guilty about that. In part that’s because he had the foresight to die before my loving stepfather thereby hogging all of my weepy “my dad died” writing before the man who actually raised me could get the chance. I wonder if he was capable of thinking about any of this stuff in the last week or two he spent in a medically induced coma at the hospital as his children and exes reemerged to say goodbye one final time. It was like a dress rehearsal. We were talking to him but he couldn’t talk back. I guess I’m doing the same thing now.

I'm afraid that my son will always be emotionally arrested at two years behind the development of people the same age who had siblings in their house, or who, like many kids in my neighborhood, had parents who thought kids were invincible to Covid-19 and let them play with whomever they wanted. I worry that he may pay a price year after year even into adulthood because other kids got to practice socializing as we rode past. They got to hang out with people their own age and run around and do vitally stupid shit and say "butts" a lot, and he got look at me heartbroken and knowing empirically and epidemiologically that he couldn't play with his friends anymore but still needing to know why, and knowing that I couldn't tell him anything more sophisticated and anything less terrifying than, "So we don't get sick."

Here's one of my favorite songs about a father.