Everything they gave us before they left

On Garth Hudson of The Band by Rax King

by Rax King

And now Garth Hudson has passed away at 87 in a nursing home and The Band has finally, officially, left the building. I’m more heartsick than I thought I could be at the death of an 87-year-old man. Hopefully that doesn’t sound callous—what I mean is that Hudson had, by any reasonable metric, an exceptionally bounteous life, and it’s possible to find a somber beauty in this final closing of the circle, to say yes, these men are all gone, but look at everything they gave us before they left! But I just feel sad, because my boys are dead.

I’ve been a fan of The Band all my life thanks to my father, who had himself been a fan of The Band all his life—well, since they released Music from Big Pink in 1968, anyway. Every Thanksgiving, we would celebrate the holiday with my mother’s family in Richmond, VA, and then my father and I would excuse ourselves after the big meal to partake of our private tradition: watching Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz together, eating two pilfered slices of my grandmother’s chocolate chess pie, no matter how logy we were from the gravy and the sleepy heat of too much family time.

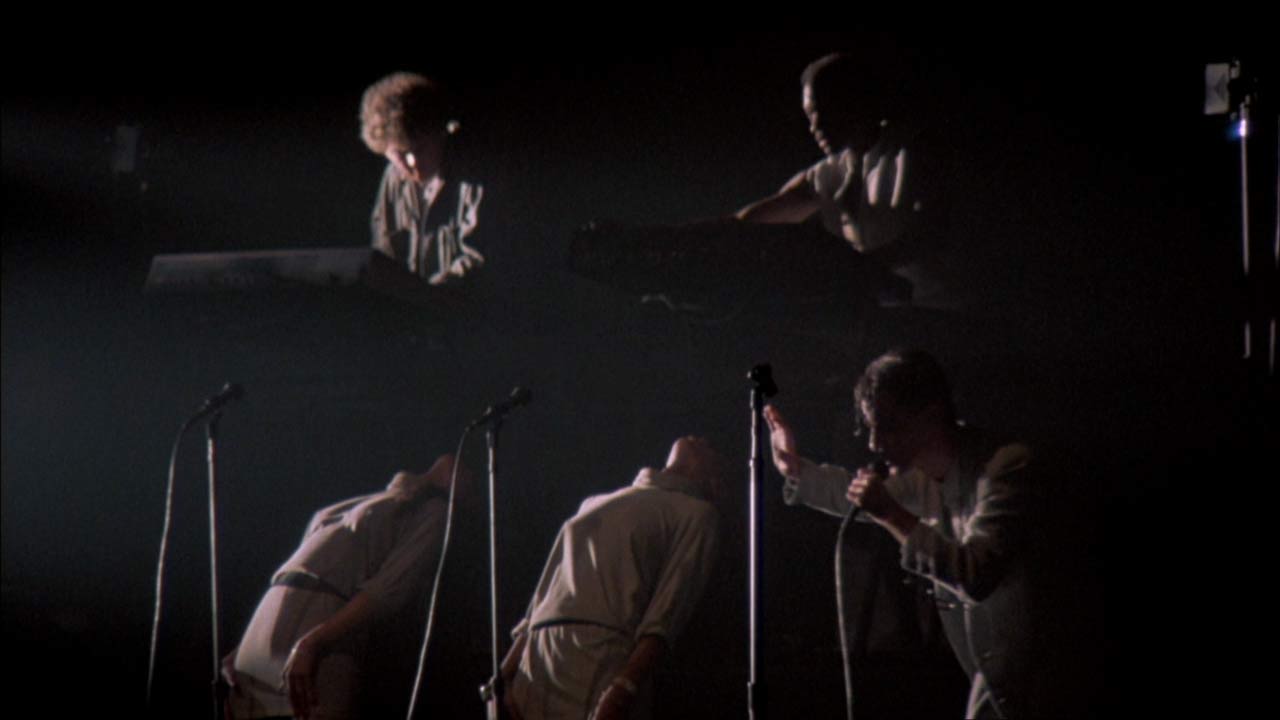

The Band’s final concert, played on Thanksgiving Day at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom in 1976, was infamously plagued with tension. According to Levon Helm, The Band’s drummer and singer and only American, none of the boys even wanted to stop touring together except for lead guitarist Robbie Robertson, who was so hellbent on getting off the road that the others had no choice but to give in. But all we saw watching the film was a group of five men (and nearly two dozen of their most famous friends) who know each other cold. They’ve been playing some of these songs for sixteen years, but, despite being so obviously lived-in, their performances never feel rote. Instead, my father and I nestled with pleasure into the coziness of the tunes we knew so well. These were our friends—the men or the songs, we couldn’t have said which—and we only got to see them once a year. The Band may have been pretty sick of each other by 1976, but we never got sick of them.

Please consider a paid subscription to support our writers.

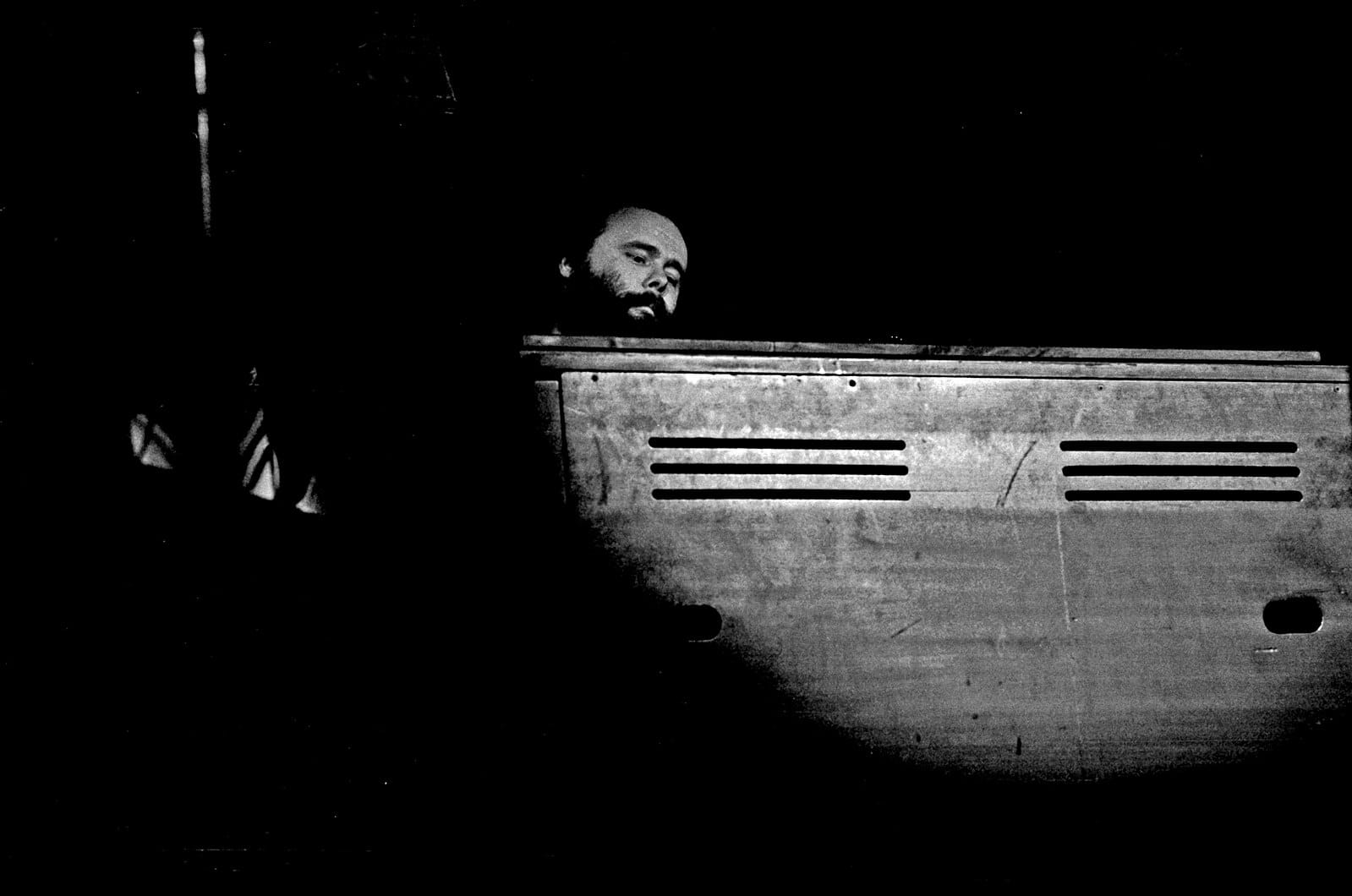

Garth Hudson is gentle and silent during many of the backstage scenes in The Last Waltz, in a way that feels partly true to his role in The Band and partly like Scorsese just wasn’t sure what to do with him. When Richard Manuel remembers shoplifting baloney in The Band’s early days, when Rick Danko explains the objective of the billiards game cut-throat, Garth Hudson is nowhere to be found. At one point, he speaks briefly about how much The Band loved the outdoorsy solitude of their house in Woodstock, though in truth only he and Helm look like they’ve spent much time outdoors lately, while the others look sickly and unshaven. At a different point, he speaks reverently about jazz musicians, “the greatest priests on 52nd Street and the streets of New York.” Only Hudson is never interrupted with a joke or a disputed fact while he’s speaking. His remarks have the thoughtful weight of koans, and when he talks, the others listen.

Hudson was the last to join what would eventually become The Band, and he was its oldest member by several years. By 1961, Ronnie Hawkins had been pestering him for months to join his backing group, then called the Hawks, but Hudson had always demurred. “I thought, I can’t play this music. I don’t have the left hand these guys do,” Hudson remembers in Levon Helm’s autobiography This Wheel’s On Fire. “The whole thing was too loud, too fast, too violent for me.” The conservatory-trained pianist felt out of place just watching this rockabilly bar band tearing up their instruments, but eventually agreed to join as the group’s organist and “music instructor”—as long as Hawkins threw in a brand new Lowrey organ. (A 1961 Lowrey organ would have cost more than $10,000 in today’s dollars.) That business about giving the band music lessons was his attempt to legitimize his new gig to his family, who were very conservative and didn’t approve of their son playing rock ‘n roll music in bars and taverns seven nights a week. Though Hudson was 24 at the time, he still didn’t want to join the band without his parents’ blessing, which they eventually, reluctantly, gave.

For all that his role as The Band’s teacher had mostly been a device to trick his parents, Hudson took it seriously. The group would be driving to a show, and Hudson would call out the chords of whatever song was playing on the radio in the car, however complicated the song’s structure, however fast its chord changes. In Helm’s remembering, it was only when Garth Hudson joined that playing music professionally really became fun—not just the drinking and grab-assing of being a touring bar band, but the music itself. He elevated them and forced them to take the work seriously. “It was like we didn’t have to guess anymore,” Helm says, “because we had a master among us.” He caroused much less than the rest of the group, tried to live a cleaner life. He brought a quiet, homespun strangeness to The Band—there’s a picture in Helm’s book of Hudson showing him how to dowse, a divination method (or, if you prefer, a pseudoscience) in which a practitioner uses a special twig to find ground water.

Eventually, when the former Hawks helped Dylan “go electric” in 1965, they became The Band, so called because the Woodstock locals always referred to them as “the band.” Their chemistry was legendary. One day, they had the good fortune to run into harmonica player Sonny Boy Williamson, an irascible bluesman who claimed Robert Johnson had died in his arms and was rumored to carry a big knife everywhere he went. He agreed to jam with them for the rest of the afternoon. He was used to dominating the English blues rock groups he was playing with at the time, but even he was impressed, calling The Band “one of the best bands I’ve heard.” And no one in The Band is more thrilling than Hudson, who may be a man of few words in The Last Waltz, but more than makes up for it with the ferocity of his musicianship. Whether it’s his lacerating tenor sax solo on “It Makes No Difference” or the whirling rainbow-sound of the organ on “The Shape I’m In,” he knows exactly what the song is missing and swirls it in like a painter mixing colors.

It makes sense that Hudson was the last of The Band’s original members to go—he was the most stable of them when he joined, and he retained that quiet, self-assured stability until the end. Richard Manuel left us first, hanging himself in 1986 after a show with The Band, who had reunited sans Robertson. Rick Danko was next, dying of heart failure in 1999 at the age of 56. Then Helm went—throat cancer, 2012. Then Robertson—prostate cancer, 2023. Then Hudson, in his sleep at 87. There’s a bitter symmetry to the way each man lived and the way he died, how sweet sensitive Manuel just couldn’t take it anymore, how Helm’s warm, achingly beautiful voice got eaten away by cancer. And now Hudson. Secure, sedate, and gone.

My favorite band is dead, and as with any celebrity death the mourning is both for the men I never knew and for the work I know better even than my own. That’s what Robertson’s death was about, and Helm’s, and Danko’s, and it’s what Richard Manuel’s death would’ve been about if it hadn’t happened before I was born, and now with Hudson’s passing there will never be another death that reminds me to play my worn out old copy of The Last Waltz. “It Makes No Difference” lives in a little hollow of my chest, convenient and accessible anytime I feel lovesick; “The Weight” is a softness in my limbs telling me to set my cares aside for awhile. I know every beat of this record and movie, and still these are two songs that always make me cry. For their openness, the earnest way they tell of hardship and loneliness and need. There’s something so sincere in playing a solo. In stepping to the front of a stage the way Hudson does during “It Makes No Difference” and gently demanding that an audience pay attention to you, specifically, because your instrument can tell them something about heartbreak that they really need to hear.

Rax King is the James Beard award-nominated author of the essay collections Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer and the forthcoming Sloppy. She lives in Brooklyn with her toothless Pekingese.

Rax most recently wrote for Hell World about the film Anora.

For another great piece about another classic concert film read Donald Borenstein on Stop Making Sense.