Waiting for the next Mr. Death

I don’t want to see anybody hurt, anybody tortured

Please help support paying for work from great contributors like today’s by purchasing a subscription.

The supreme court in South Carolina recently halted the execution of two men until they are able to choose between being electrocuted to death or killed by a firing squad. The problem is the state didn’t happen to have a firing squad handy. As for the condition of their electric chair well that’s what today’s piece is about. Paul Bowers who writes the great newsletter Brutal South looks into capital punishment in his state and elsewhere and catches up with Fred Leuchter the now discredited architect of execution devices that were in use throughout the country for decades.

For more on some of the legislating going on in South Carolina like the recent law that brought them to this death impasse read Dave Infante’s piece in here We want you to suffer and die 😄

You might also appreciate Jack Crosbie of Discourse Blog weighing in on the repugnance of the death penalty

or this piece by me concerning a Black man named Isaac Woodard who was beaten and blinded by police in South Carolina in 1946 and one of Orson Welles’ most righteous monologues about the injustice of it all.

Waiting for the next Mr. Death

Fred Leuchter cornered the market on executions in the ‘80s. Who will take his place?

by Paul Bowers

If you were a U.S. prison warden trying to figure out how to kill people with an electric chair in the ‘80s, there was basically one guy to call. His name was Fred A. Leuchter Jr.

He ran a business out of his house in the Boston suburbs, providing consulting or execution equipment to at least 27 states between 1979 and 1990. Some of Fred Leuchter’s equipment is still in use today, which is why I wanted to talk to him.

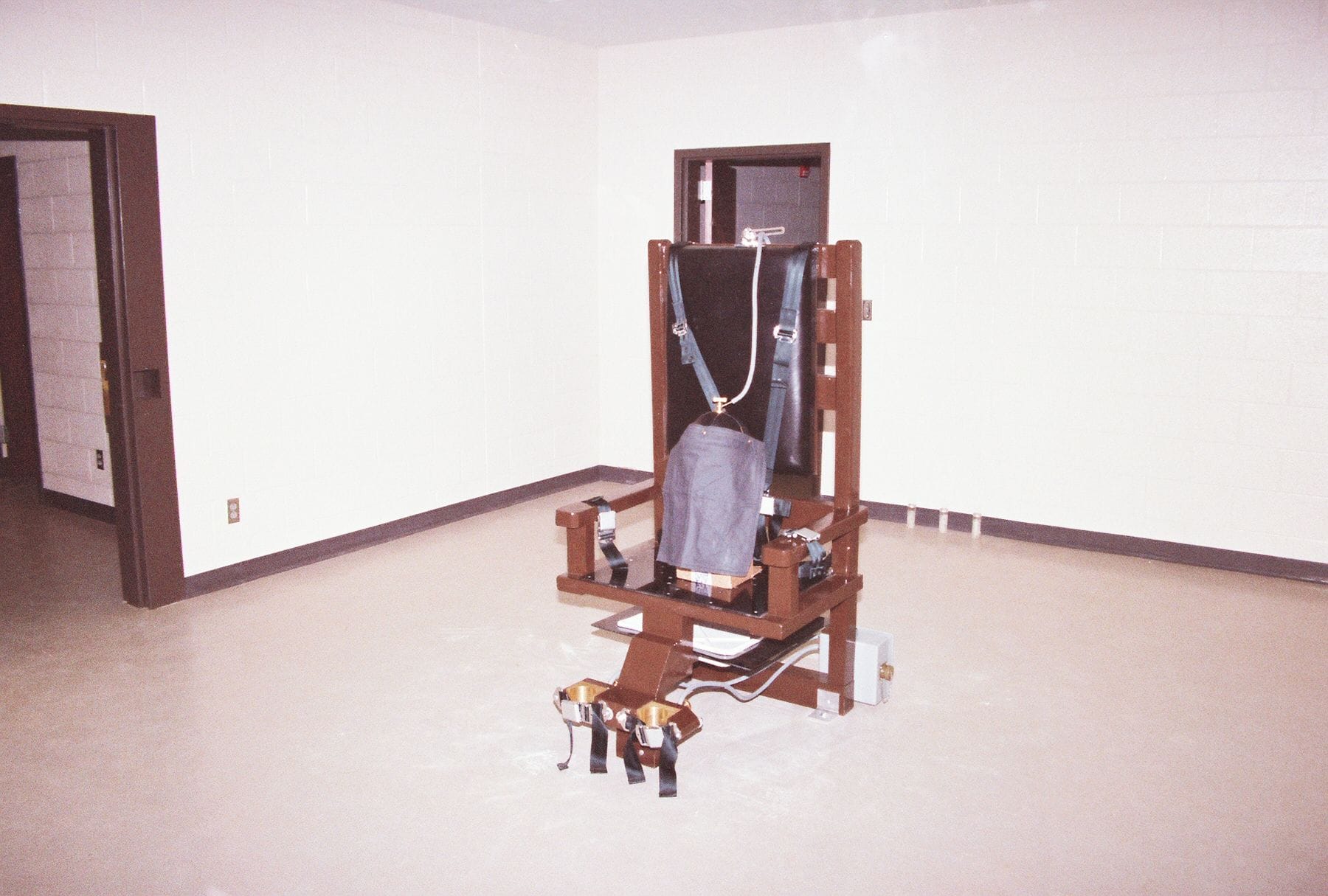

In South Carolina, where I live, the Department of Corrections is on the verge of either killing an inmate with a firing squad or electrocuting someone for the first time since 2008. They nearly electrocuted a man named Brad Sigmon on June 18, but the state Supreme Court stopped them at the last minute because technically they hadn’t assembled a firing squad yet and they needed to give Sigmon a choice of how he died.

If South Carolina electrocutes someone again, there’s a good chance they’ll use equipment that Leuchter sold them. He went on the record with the Greenville News in 1991 saying he had sold an electrocution helmet to the state for $800 in 1983.

Leuchter — pronounced “LOO-cher,” with a silent T — has been outspoken about the risks of improper maintenance of his machines. He gave some ominous warnings about the one he built in Tennessee before they fired it up again in 2018 (“I don’t think it’s going to be humane,” he told the AP).

I wanted to hear his thoughts on South Carolina’s chair, so I called him this week at his home in Malden, Massachusetts. He wasn’t hard to find. He listened to my introduction and briefly launched into the finer technical points of electrocution before cutting himself off.

“Are you familiar with my background?” he asked.

I was. Because I oppose the death penalty on moral grounds, I had been reading about his singular influence on the legal and technological framework of the death penalty in America. I had watched Errol Morris’ 1999 documentary about him, Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr., and I recognized his pinched New England accent over the phone.

“Then you know I was an expert witness, and I testified in a lot of different courts here and abroad on capital punishment,” Leuchter said. “At any rate, you’re also aware of the fact that because I testified in Canada for Ernst Zündel, the Jewish organizations and the Nazi hunters and all these people came after me and they effectively put me out of business.”

I’ll note here that in the course of a 1-hour interview, Leuchter brought up “Jewish organizations” 4 times, and also claimed he had been maligned by “a Jewish attorney general” and “a Jewish representative.”

If you’re wondering why Leuchter isn’t working in the death penalty business anymore, the Zündel trial was the beginning of his unraveling. In 1988 a neo-Nazi named Ernst Zündel went on trial in Canada for distributing a Holocaust denial pamphlet called Did Six Million Really Die? The Truth at Last. Zündel’s case became a cause célèbre for anti semites, and his legal team rolled out a series of expert witnesses seeking to bolster its ahistorical claims.

Leuchter took a job as a paid expert witness for Zündel’s legal team. To prepare his testimony, he traveled to Auschwitz, scraped some samples off the bricks of a gas chamber while his wife and translator stood lookout, and sent them to a lab to be tested for traces of cyanide.

Leuchter concluded that the chambers could not have been used for homicidal gassing, contradicting the eyewitness accounts of survivors and guards as well as the blueprints and records of the Third Reich itself. His prepared findings, known as the Leuchter Report, were dismissed by the judge as “preposterous” and were immediately and repeatedly debunked by the international scientific and historical communities.

The Zündel trial made international news. Aside from his errant beliefs about the Holocaust, the trial had revealed something else about Leuchter: He had no formal training as a toxicologist, medical doctor, or electrical engineer. When questioned by the court about his credentials, Leuchter had touted a bachelor’s degree in history from Boston University. This raised questions about his day job as well.

Back in the U.S., Leuchter continued to get work in the execution business anyway. He still had a contract for a lethal injection machine in Colorado as of July 1990, and he even had a bid in to inspect Arizona’s gas chamber as late as December 1991.

In October 1990, a group from Albany, New York, called Holocaust Survivors and Friends in Pursuit of Justice filed a complaint with the state of Massachusetts alleging that Leuchter was practicing electrical engineering without a license.

The state took up the case. Rather than go to trial and face three months’ imprisonment, Leuchter reached a settlement in which he agreed to stop distributing reports claiming that he was an engineer. This was the end of his career as a death penalty expert, at least publicly.

“Wardens would turn around and say, ‘We don’t know anything about Fred Leuchter, we haven’t dealt with him,’ and then two hours later they call me up on the telephone and say, ‘Hey, we’ve got an execution scheduled and I’m having a problem with the equipment, what do I do?’” Leuchter said.

There’s no moral or practical justification for the death penalty no matter how you do it. It’s cruel and arbitrary and it doesn’t act as a deterrent. It brutalizes the people who carry it out and traumatizes the families of murder victims, and particularly in this country the pattern of its application is openly racist.

It’s not a moral gray area to me. All that being said, I think it matters if the state I live in is still using equipment that it bought from a self-taught electrician with a shaky grasp on the scientific method.

The South Carolina Department of Corrections has neither confirmed nor denied that it has Fred Leuchter’s electric chair helmet installed in the death chamber at Broad River Correctional Institution.

“The department doesn’t have any records about this, and even if it did, the records would be restricted and not considered public under FOIA,” department spokesperson Chrysti Shain wrote to me in an email. (I plan to submit a Freedom of Information Act request anyway.)

I asked who had been performing maintenance on the electric chair. She wrote back:

“Over the years, the electric chair’s electrical components have been updated as needed and as technology has improved. Specifics about this are restricted.”

If the state of South Carolina never did business with Fred A. Leuchter Associates Inc. in the ‘80s, it would be a rare exception to the rule. And if the state bought a new helmet to replace Leuchter’s, I would be curious to know who built it. With the possible exception of Jay Wiechert, who is dead now, no one has made their name in the business like Leuchter did.

Leuchter either installed or did work involving electric chairs in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Nebraska, Ohio, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, according to a 1994 legal analysis by Fordham Law professor Dr. Deborah A. Denno published in the William & Mary Law Review.

Specifically in South Carolina, Denno wrote that the state bought his helmet, that it used “a Leuchter-designed electric chair or components,” and that Leuchter “‘works closely’ in order to maintain the electric chair.”

While Leuchter was best known for his work on electric chairs, he also consulted on nearly every form of execution in use at the time. He even designed a special sleeve for Delaware’s gallows rope to prevent rope burn. At the peak of his career he claimed he was pulling in a quarter-million dollars a year.

“Every single state in the country was having the problem, and what they did was they passed my name around,” Leuchter said on the phone. “And I was getting calls, and I was on a first-name basis with the wardens and commissioners in all of the states that had capital punishment. They were all saying the same thing: ‘Help us so we don’t torture people.’”

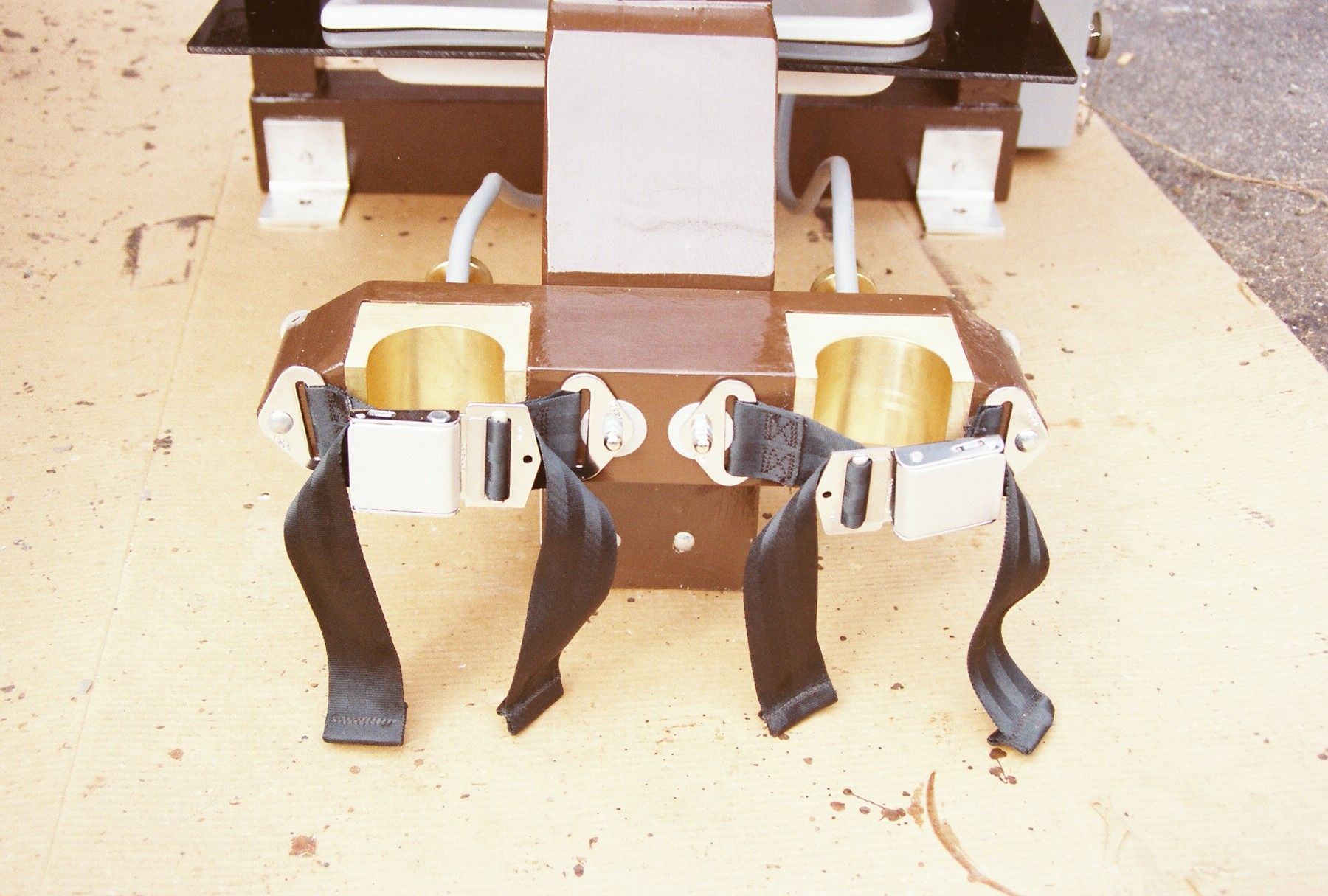

The Leuchter helmet has two components: A leather outer helmet and an inner mesh made of copper. The current flows through a bolt, unlike older models that were soldered together.

I asked him how confident he would be in his machinery today if the state of South Carolina were to use it.

“Well, it depends upon how well it’s been maintained,” he said. The electrodes and washers would need to be cleaned with steel wool. Additionally, fhe thinks the state should retrofit its 1912 wooden electric chair base with his custom-designed leg stocks, which hold the body still during electrocution and ensure that current flows through both sides of the body.

And then there is the sponge. Inside the copper mesh, there should be a layer of sponge that corrections officers will soak in ammonium chloride shortly before the execution. If this is done improperly or with the wrong kind of sponge, the execution could turn hellish.

During Florida’s electrocution of Jesse Tafero in 1990, the sponge in the helmet caught on fire. Flames shot up from Tafero’s head, and witnesses smelled his flesh cooking. It took three jolts over the course of seven minutes to kill him.

The state of Florida laid the blame on Department of Corrections workers who had replaced the natural sea-sponge lining of the helmet with a synthetic household cleaning sponge, which had a different level of resistance. Leuchter disputes this and has argued that synthetic sponge is actually preferable for its uniform thickness and density. He thinks the state should have installed leg stocks on its chair.

He would like to advise the South Carolina Department of Corrections before they electrocute someone again. He has detailed drawings of electrodes and chair components that he wants to share with the state.

“If you’re talking with them, I’ll be more than happy to send them at no charge,” he said. “I don’t want to see anybody hurt, anybody tortured. That’s why I became involved in the first place.”

Leuchter has said in interviews over the years that he got involved with capital punishment via his father, who was a corrections officer. After witnessing some executions and reading about botched ones, he started researching execution methods that he considered more humane.

Part of the reason Leuchter was able to corner the market in the ‘80s was that many U.S. states were ramping up executions after a short hiatus, and there was a dearth of experts. The U.S. Supreme Court had created a de facto moratorium on executions in Furman v. Georgia (1972), but allowed them to resume under new sentencing rules with Gregg v. Georgia (1976). State legislatures, including South Carolina’s, scrambled to update their death penalty laws for compliance with the Gregg standards.

The states met resistance. In 1977, every Black member of the South Carolina House of Representatives staged a 6-day filibuster to block the bill authorizing electrocutions to resume. They reasoned that then, as today, the death penalty was arbitrarily and disproportionately used to kill Black men and those convicted of murdering white victims. The bill passed anyway.

A lot of electric chairs in the U.S. date back to the late 19th and early 20th century, and they were built in many cases either by prison labor or by hobbyist inventors much like Leuchter who figured things out via trial and error. According to Leuchter, many states’ electric chair equipment was badly aging and had been poorly maintained in the interim leading up to the Gregg decision. In one state, the manual for an electric chair crumbled in his hand as he tried to open it.

“The problem was they hadn’t done it for so long, most of the people that did it were either dead or retired,” Leuchter said.

Today some state governments are searching for experts after an even longer hiatus. South Carolina, for example, has not used its electric chair since 2008 and hasn’t carried out a lethal injection since 2011. There are 37 people on our death row. The state’s supply of the drug cocktail used in lethal injections expired in 2013 after pharmaceutical companies refused to sell the drugs, effectively stopping executions. The new law authorizing the electric chair and firing squad is meant to work around this obstacle, but it means they have to fire up a killing machine they haven’t used in 13 years.

Today when states need someone to inspect their electric chair, they don’t call Mr. Death — and it’s not clear who is qualified to take his place.

“They’re in much the same situation they were when I got involved back in the late ‘70s,” Leuchter said.

Leuchter isn’t just flattering himself. Writing in 1994, Dr. Deborah W. Denno described Leuchter’s downfall this way:

[H]is loss is significant if for no other reason than that no one else has replaced him. States that have not enforced the death penalty in a long time have difficulty finding executioners. Other states have trouble locating technicians who can repair or replace electric chairs, or construct lethal injection machines. The number of botched executions that have occurred within recent years accentuate the need for experts.

We may be entering a small gold rush for capital punishment contracts, and the next prospectors might not be as scrupulous.

In 2014 the state of Oklahoma tried an experimental lethal injection cocktail on a man named Clayton Lockett. Witnesses watched for 43 minutes after his sedation as he writhed, bled, groaned, and spoke about his agony before dying.

Numerous states including South Carolina have considered or passed “shield laws” that protect the identity of companies that sell them lethal injection drugs. In 2017 the state of Texas nearly bought lethal injection drugs from a group of entrepreneurs who also sold Xanax and Ritalin to partiers out of a shopping mall in Gujarat, according to Buzzfeed News.

In May The Guardian revealed that the state of Arizona was purchasing the chemical components to manufacture Zyklon B, the hydrogen cyanide gas that the Nazis used at Auschwitz.

Less is known about the state of the electric chair industry, in part because states like South Carolina refuse to answer questions about it.

Fred A. Leuchter Jr. is retired now, but he wishes he wasn’t. He told me he worked in the hardware department at a Home Depot in Somerville a few years ago, but someone figured out who he was and got him fired.

“I keep getting fired,” he said. “I agree it’s a step down if I’m selling hardware in Home Depot from working as an engineer, but I’ll do anything. Unfortunately nobody wants me to do it for them.”

He said he lives frugally and gets by on Social Security checks now. I asked him if he had any regrets about his career working in capital punishment.

“No, not really. I got into this because I had to,” he said.

The themes of duty and inevitability came up again and again. He saw people being tortured to death and he had to do something about it.

“My feeling is that if we’re gonna execute people, we need to do it right and humanely,” he said.

He expressed sympathy for the corrections officers whose job it is to pull the switch, or push the syringe, or pull the trigger as the case may be.

“As the warden you are the care and custody of that inmate, and it’s almost like you’re having to execute your own son when it’s time to do it. You’ve taken care of that man for 10 or 15 years, and now you’ve got to kill him. In some of the states, you have to pull the switch yourself, and that’s a terrible thing to act on the conscience of the warden,” he said.

“As I say, the whole system is terrible from that standpoint, but you don’t have a hell of a lot of choice. You got the job, you do the job.”

You got the job, you do the job. Also known as the Nuremberg defense.

Paul Bowers (@Paul_Bowers) is a writer and former newspaperman from North Charleston, SC, who is working on a book about brutalist architecture in the American South. He runs a newsletter and podcast called Brutal South. He previously wrote about the death penalty here, here, and here.