They’re a faceless organization that will take you to collections if you don’t pay your bill

Here's how much that just cost you

This summer my young niece passed out. She was woozy and something seemed really wrong so my sister did what any mother might understandably do she freaked the fuck out and called an ambulance. They took her to the hospital and checked her out and ultimately she was fine it wasn’t anything serious thankfully. But then a while later the bill came.

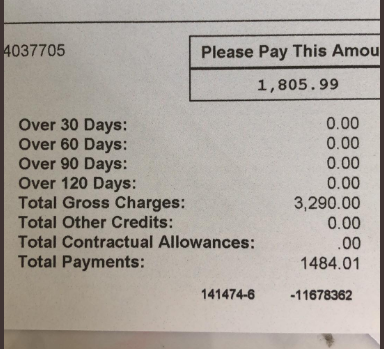

Although my sister’s family has “good” insurance the ambulance ride ended up costing exactly $3,290 for some reason no one knows why and the insurance company decided to pay exactly $1,484.01 of it for some reason no one knows why and my sister was on the hook for exactly $1,805.99 for some reason no one knows why. The perfect system.

I have no idea what the decision making process was that led to the insurance company paying exactly $1,484.01 instead of $1,484 or $1,485 or literally any other amount for that matter but you could write a book about that single penny alone and it would be called Fuck You: The History of Capitalism. Or maybe call it Welcome to Hell World: Dispatches from the American Dystopia that’s also a good book title in my opinion.

Fortunately my sister is fairly well off and come to think of it all my sisters own homes and have children while I do not maybe I should look into that hmmm actually no I will ignore it and so this bill will not significantly impact her life but for many millions of other families around the country it would.

Do you have $2,000 kicking around you could spare at the moment? If your child fell seriously ill would you say hmm maybe I better wait this out and see if they get better on their own because of the potential cost or would you say fuck it and call an ambulance which is essentially pulling the life or death slot machine lever of healthcare to see what random numbers popped up at the end. Ding ding ding. Surprise! Fuck you.

I was reminded of a chapter from my book which you can read here where I spoke to numerous people who had declined to call an ambulance when they were injured because they were worried about how much it might cost.

“I always joke to my friends that if they find me dying, and they call me an ambulance, I’ll come back from the dead to fight them because it’s so expensive,” one of them told me. “But that joke comes from a real place of fear of being stuck with a bill I can’t pay.”

I heard stories about people who had their credit permanently destroyed after a handful of ambulance rides being transferred between hospitals not fully aware of what was happening and not really in a position to object. People spoke of walking to the hospital and almost passing out along the way with severe burns or lacerations. More than a few told me about having to get into arguments with the EMTs telling them in no uncertain terms that no they did not have to go with them. Others weren’t so adamant and regretted taking the ride when police or emergency personnel were more insistent.

I was also reminded of this story from last year when a woman in Boston got her leg crushed by the subway which is fucking tragic but also demonstrably Peak Boston Lady and I have to admire it.

Outrage over surprise ambulance bills has been gathering steam of late and has started to be covered by the media more widely like in this piece from the Washington Post:

One patient got a $3,660 bill for a four-mile ride. Another was charged $8,460 for a trip from a hospital that could not handle his case to another that could. Still another found herself marooned at an out-of-network hospital, where she'd been taken by ambulance without her consent.

These patients all took ambulances in emergencies and got slammed with unexpected bills. Public outrage has erupted over surprise medical bills — generally out-of-network charges that a patient did not expect or could not control — prompting 21 states to pass laws over the years protecting consumers in some situations. But these laws largely ignore ground ambulance rides, which can leave patients stuck with hundreds or even thousands of dollars in bills and with few options for recourse, finds a Kaiser Health News review of 350 consumer complaints in 32 states.

People like this fucking audience-tested A.I. with a weaponized resume sent back from the future to explain to humanity that better things aren’t possible like to say that Medicare For All can’t work because people want to mAkE cHOiCes ABoUt tHeIr HEaLth care and that’s obviously stupid but it’s even rarer that you have time to make a choice when you’ve been injured. Often the ambulance has been called or has arrived before you’ve even had a chance to scream ah fuck what the fuck.

Patients usually choose to go to the doctor, but they are vulnerable when they call 911 or get into an ambulance. The dispatcher picks the ambulance crew, which may be the local fire department or a private company hired by the municipality. The crew, in turn, often picks the hospital. Moreover, many ambulances are not summoned by patients, but by police or a bystander.

Further complicating this entire mess are the same people that further complicate every mess in Hell World the blood guzzling equity vampires who have moved into the emergency care space. As the New York Times reported:

The business of driving ambulances and operating fire brigades represents just one facet of a profound shift on Wall Street and Main Street alike, a New York Times investigation has found. Since the 2008 financial crisis, private equity firms, the “corporate raiders” of an earlier era, have increasingly taken over a wide array of civic and financial services that are central to American life. …

That includes ambulance companies. You will not be surprised to hear that when profit is the primary motivator for the people behind these companies the quality of care tends to go down and especially for the more vulnerable among us.

While private equity firms have always invested in a diverse array of companies, including hospitals and nursing homes, their movement into emergency services raises broader questions about the administering of public services. Cities and towns are required to offer citizens a free education, and they generally provide a police force, but almost everything else is fair game for privatization.

“We’re reaching new lows in the public safety services we will help provide, especially in very poor cities,” said Michelle Wilde Anderson, a law professor at Stanford University who specializes in state and local government. Private equity firms, she said, “are not philanthropists.”

“Under the new paradigm of private equity,” as this good piece in the American Prospect points out, “poorly maintained ambulance services siphon profit from vulnerable patients.”

brb I gotta go to the brain hospital real quick no one call an ambulance.

In light of all of this I decided to speak with a veteran paramedic about his experience working on an ambulance off and on over the past twenty years. We talked about the absurdity of arbitrary billing procedures, the conflicts between ambulance companies and insurance companies, and what happens when someone refuses to get in the ambulance when they arrive.

What’s your experience working in emergency services?

I started as an EMT before college and worked through college, then I became a paramedic after for a couple years. Part way through school I went back to it part time on and off, and then did another eight years full time after that. I stopped three or four years ago. All together about twenty years.

Oh weird I never really thought of it as something you do as a part time job, like waiting tables or something, while you’re going to school.

A lot of people do it. There’s a lot of firefighters that do it, certainly in Massachusetts, as firefighter paramedics, then they do it part time for additional hours at private services. There were guys who worked for Boston Fire, and were paramedics, and wanted to stay active, so they would work for private ambulances on the side. The running joke was always that it’s Dozing for Dollars. It’s not so much that anymore because it’s much busier than it used to be.

In a way these billing practices are still sort of the Wild West, right? There’s littler oversight and regulation?

I’m originally from upstate New York, and it’s a much different area there, where it’s basically state regulated competition. Massachusetts is kind of a free-for-all. If you have a dollar and a dream you can start your own ambulance service. In New York you have to apply for permission to compete with anybody, so there’s very little competition. The reason that’s relevant is there is a much lower number of private service providers, and because of that everyone signs preferred provider contracts with any or all of the insurance companies in the area. The thing that happened to your sister probably wouldn’t have happened there, unless they were from outside the area and had some crazy out of the area insurance.

You work at these commercial ambulance agencies, like I did for years, and you start to get very cynical about them. Generally people’s hearts are in the right place who work for them. I’m forty two now, and I think about the person I was when I was younger, and the kids that go to work for them now, a lot of them are trying to get on fire departments or police departments. They’re doing something in the public safety area to try and get in that career field. They come in idealistic wanting to help people. But I’ve seen over the years how the business of a lot of these private sector emergency services really use people. They operate at a very thin margin on one hand, so I’m sympathetic to that, but on the other hand they have no qualms about justifying everything on the basis of: But we’re an ambulance service.

In the Washington Post article I sent you, a guy in Brookline kind of got caught in the middle of the insurance company, I think he had UnitedHealth, and Fallon, which was the ambulance service. And Fallon’s answer was, Well, we feel terrible but we have to get paid for this service. But there’s no sympathy for the patient in any of that. That’s usually their answer in any of these circumstances.

I started raising a stink a while ago, because I have the unfortunate burden of having gone to law school, and learning about labor law. Over and over the answer you get from these companies [about many criticisms] is that, well, this is EMS, so it doesn’t count. There’s this overarching that doesn’t apply to us attitude from these companies and they feel they should be afforded exceptions to the rules, while at the same time taking advantage of any situation they can get their hands on if it applies to them.

Do you think there’s a measurable difference between how private and public services act?

I think so. When I started working at Cataldo in 2008 they were the contract ambulance for city of Melrose, MA. In the time I worked there Melrose Fire started their own ambulance service. If you live in Melrose and you had a problem with Cataldo’s ambulance service, Cataldo doesn’t answer to anybody. There’s no one you can really go to with your complaint or concern about what happened on the ambulance because they’re a faceless organization that will take you to collections if you don’t pay your bill. If the fire department ambulance sends you a bill and you feel the bill is too much as a taxpayer for the town, whatever billing agency they use can still send you to collections, but you could at least take that up with the town manager or somebody who answers to somebody. The fire chief answers to the mayor. You have some means of accountability there.

And the other part of the equation is, at a private company — and I’m not bashing Cataldo, whether it was AMR, Fallon, or anybody it’s the same — whether it was me or someone else, it was whoever happened to be there that showed up for the call. It could be a guy coming off a 24 hour shift somewhere else, the brand new guy they got out of paramedic school from two weeks ago. There’s no cap federally or at the state level about how many hours an EMT can work. You could get an EMT that’s just worked forty hours. At least on a fire department, you might get the most average paramedic on the street, but more likely than not it’s going to be a career guy who knows all the streets in the town, who’s going to be accountable to that job, and who has some vested interested in at least showing up on time and being polite to the people he serves because he wants to be on the fire department for the next twenty years.

Didn’t Cataldo get sued by the Attorney General for over-billing in Massachusetts? They were fined $600,000 or something.

They all do from time to time. This is not Medicare. If you’re just some guy on the street and you trip and fall private ambulances will bill you for the line item for oxygen, or the bandaging you got. For every specific item. So instead of some flat fee plus the mileage, an all you can eat kind of bill like they charge Medicare, they would add up each thing and code in the paper work in the chart. I believe, and I never worked in billing so I don’t know this first hand, but my understanding is that they itemized everything they could and then billed it individually. What I heard, and I’m not positive, was you’re not allowed to do that in Massachusetts, and that’s why the Attorney General went after them in Massachusetts. I think they were required to make repayments to the state.

So it’s like when you go to the hospital and you get the bill and there’s a line for $12 for an ibuprofen or something?

Right. Adam Ruins Everything has a great episode on this. The idea is, the fees for everything at a hospital, none of it is real. They just make up charges for everything in the hospital, but no one actually gets charged that. It’s just a negotiation table they use for each insurance company to come up with a rate for this particular patient or service. Medicare is all different. If you go in for a hip replacement, say, Medicare will automatically pay $x for the hip replacement, from the time you check in until the time you check out. If it’s any other insurance it’s a line item for everything you do.

Would Medicare For All change these problems with ambulance pricing in your opinion?

With Medicare there’s such an established pattern of the way the rules all work in every market in the country. Basically everyone takes Medicare or you’re not in business. In Massachusetts in order to be an ambulance service, you’re required by law to accept Medicaid Assignment, which means you have to accept the Medicaid payment, and not balance bill. So let’s say your sister had Medicaid, or Mass Health, if they only paid $100 for the ambulance bill, the ambulance service would have to take the $100 and eat the cost. Medicare has an analogous rule. If you agree to be a Medicaid Part B supplier then you agree you will not balance bill the patient for the remainder of the ambulance bill.

In all but a tiny fraction of Medicare cases — some hospital-owned ambulances — 911 ambulance calls are billed to Medicare Part B, so the patient would end up paying some copay, but it is still covered by Medicare under present-day rules. A lot of seniors have supplemental or Medigap insurance that I believe covers these kinds of 20% copays. I suspect any reasonable M4A plan would have to address these kinds of situations as well.

When we go on a call, and bill it to Medicare, there are five or six different levels of service, and it’s a flat rate for each, from basic life support on up. Then mileage on top of that. If Medicare applied to that situation, it would be flat, instead of being line-itemed for each individual thing we did, then accounting for each ambulance service or municipality’s crazy, arbitrary dollar value for what the ambulance ride costs today.

So you’re saying with Medicare it’s pretty straightforward. From one to five level of care, you go we did roughly a two-level of care on this call and we’re going to charge them a two. If they’re on the brink of death, and it’s a five, you’re going to charge a five. Whereas now they sort of bullshit it and toss in this and that.

It seems to me the analogy would be on Medicare you go to a restaurant and you pay $30 flat for a steak, but without Medicare, on the bill it’s going to say $1 for the salt, $5 for the garnish etc.

Right. And with Medicare you know any restaurant you go into you’re going to pay $30 for the steak. With private insurance you don’t even get to see the prices on the menu.

You said you saw instances of people getting worried about transport because of the cost in your day.

I did. It’s been thousands of patients and calls so they all blend together. But one that sticks out the most was one I saw reported on in the Boston Globe and New York Times that’s a better concrete example than any I could point out. But the anecdotal cases I saw it was mostly like college and college age kids who have crappy entry-level insurance with high deductibles, and they know they’re going to get slammed with an ambulance bill. Somebody called the ambulance for them, or they passed out at a bar, or something stupid, and they don’t want to get the bill. They’re literally going to get a ride themselves to the hospital. That happens a lot. A lot of times I think we don’t find out about it because they didn’t call the ambulance in the first place, so I suspect it happens a lot more than I personally witness.

I’ve gotten into fights with doctors over the phone before, because doctors oversee paramedics in the field. I’ve had them be really obtuse to me on the phone, like if I’ve woken up a patient with Narcan, they’re awake and alert and don’t want to go to the hospital, and they’re there with family, I’ve had doctors tell me, no you have to force them to go. I say I can’t force them to go if they don’t want to go. The doctor is telling me restrain him if you have to, and I say I’m not going to restrain this guy he just started breathing again.

Let’s say you show up and I look pretty bad but I’m like fuck you I’m not going. Can you force me to go?

There were cases where I basically said that the patient is acting so irrationally against their interest, that even though they’re telling me they don’t want to go, ethically I cannot honor their wishes. There was this guy, it wasn’t even an insurance issue, he was having chest pain and his co-workers called for him. It was right before Christmas and he didn’t want to go and screw up his family’s plans. We did an EKG on him, and he was having, what looked like to us, the big one, and we said dude you have to go. He said, no no, I’m supposed to be at my family’s. No, you need to go. We run into those once in a while. Those are tough patient care situations. But if it’s not life threatening it’s really a tough sell for me to tell you you have to go.

What about the issue of which specific hospital you take patients to?

There are very few hard and fast rules that tell you where you’re supposed to take your 911 patients, and there’s a lot of leeway as to where you can go. In Malden, where I worked the most full time in my career, the company wanted me to stick around Malden as much as I could, so I would go to the local hospital. But if there’s trauma, I’m going to Mass General in Boston. If it’s something a local hospital can’t handle, I’m going out of the area.

But there are patients, for insurance reasons, an in-network hospital versus out-of-network hospital, that are requesting to go somewhere else. A lot of times, say, your hospital might be Lahey Hospital up in Burlington, but there’s a lot of traffic, and it may be in your best interest to go wherever is closest. Understandably, if your insurance wants you to go to Lahey, you want me to take you to Lahey. But there’s nothing that says I have to. So you end up in a hospital that’s out of network, and then you end up with a second ambulance ride from there to your in-network hospital, because some doctor wants to admit you. Now you have this bill that may or may not be covered for the second ambulance ride. There’s always this finger pointing that goes on when that happens. Patients’ families say Oh you took him to the wrong hospital. I never felt any pressure from private ambulance companies to go to the first hospital so we could get a second bill paid to do the transfer later. I don’t think that’s really a thing. I do think there’s pressure to go to the closer hospital sometimes so you can get back in service and be available for another 911 call.

The Hell World version of that scenario is like, say, call centers for insurance companies, who instruct their reps to get people off the phone as soon as possible so they can service as many people as quickly as possible to save money. Volume. But there’s an understandable argument here. You don’t want your ambulance stuck on the highway in traffic, so I sort of get that.

The main problem here, as I see it, is that ambulances and insurance companies can’t agree on what it should cost to ride an ambulance.

Correct. A few years ago Blue Cross and the ambulance services were dicking around with each other. The state was going to sign legislation to force them to have some kind of agreement. Blue Cross didn’t want that and they started lobbying heavily against it. So what they started doing, when Cataldo would submit their claims for an ambulance ride, $3,200, $4,500 whatever the arbitrary price was, they’d submit it to Blue Cross, and Blue Cross would turn around and instead of paying the claim to the ambulance service electronically, they would send a check directly to the patient. They would tell the patient you should send this to the ambulance service. Because of the reality of life in Massachusetts, and some of the communities they serve, a lot of patients would endorse the check, deposit it, take the money and run. The ambulance company could chase the patient for the money but it made the administrative burden of getting it much harder.

This is all complicated and hard to think about, but the bottom line is a lot of these problems wouldn’t exist if there was nobody looking to make money off of this. If these health care services were supposed to be merely self-sustaining, and everybody involved made a nice salary, sure, but there wasn’t some scumbag scraping off of each transaction, it would all be easier?

I think so. The root of the whole problem is that in the U.S., the only way for an ambulance service to recover costs from doing calls is to bill patients. Unless you’re municipal and raise taxes. And the only way you can bill patients is if you transport a patient. So if you go to somebody’s house to provide a service, if you don’t actually transport a patient from home to the ER, the most expensive place to do any patient care in the entire health care system, you can’t make any money. Obviously anyone who’s out to make a buck has found a way to tweak the system.

Then there are a lot of venture capitalists buying up ambulances for some reason.

In the late 90s AMR consolidated a lot of ambulances services around the country. There was another big company called Rural Metro that did the same thing. I think a couple years ago they folded into AMR.

Another thing that’s newsworthy about all this is these med-flight ambulances. All the hospitals that have surgery residency programs in Boston, somehow, magically, and I don’t understand it, fund Boston Medflight. But in other parts of the country, like here in West Virginia, all over upstate New York, I think there are two, maybe three, major players. One of the biggest players in the space is called Air Methods. It’s this for-profit company that has pushed a lot competition out of the market. And because they’re an air medical service, states can’t regulate what they charge. There’s been some attempts to have Congress regulate what air ambulances charge patients. There have been families that have lost their shirts for five and six figure bills.

Instead of $3,000 we’re talking $50,000-100,000 for a helicopter.

Easily. It’s not a major problem in the northeast because most of us are close to a hospital, but you go to somewhere like Montana or Arizona, they use helicopters a lot more. You go to rural Kansas, you have a rinky dink little hospital. Someone comes in with a hear attack, they get flown from that small hospital to the big city hospital so they can get appropriate care. That’s gonna be a giant bill. And nobody asks if you want a helicopter ride, they just sign you up for it, and tell you later here’s how much that just cost you.