They can and will ruin everything you love

by Miranda Reinert

This was sent out as a part of today's Hell World newsletter. Find the rest here and please subscribe if you like what you read.

In March of 2022, Bandcamp was acquired by Epic Games, the folks behind Fortnite and Unreal Engine. While the change in ownership raised eyebrows and triggered endless jokes, the site seemed to stay running much the same at first. Just over a year later in May of 2023 it was announced that Bandcamp’s employees voted 31-7 to unionize as Bandcamp United and were to be recognized by Epic. All the while Bandcamp Daily’s distinctive editorial coverage continued. Their popular Bandcamp Fridays – an initiative started in 2020 in which the site forgoes their 15% fee of sales on the first Friday of each month – also continued. So far so good.

Then at the end of September 2023 it was announced that Epic would be selling Bandcamp to content licensing and service company Songtradr. As of their initial statement regarding the acquisition, Songtradr is planning to continue Bandcamp Friday, keep Bandcamp Daily, and maintain all current features, but they were clear that not all employees would be retained. As with all layoffs, this decision was presented as a necessary evil – there’s simply no way they could run this company with all those employees! – but they swore to you, their darling consumer, that you would feel no effects.

Needless to say, having observed one single corporate acquisition before, Songtradr didn't recognize Bandcamp’s union, and employees remained in limbo for weeks before it was finally announced who would be let go – 60 of the 118 employees, slashing 50% or more across all departments, including half of the Bandcamp Daily editorial staff and 70% of the vinyl team. SFGate reports that the layoffs disproportionately impact those eligible for union membership, including every member of their 8 person bargaining team. But don’t worry about that! Songtradr loves your community! Their CEO is a “passionate musician” himself. You can trust him. Paul Wiltshire would have you believe his company is aligned with artists, even if he comes at music with beliefs like “music as a whole is inherently more valuable as a consequence” of catalog sales – i.e. the transfer of entire catalogs of music to venture capitalist firms looking to exploit copyrights they had no hand in creating. It’s a trend underscored not by increased value of art, but a change in who is able to actually profit off art. The current state of the music industry has devalued music to the point massive artists will make more money selling off their rights than they can off sales.

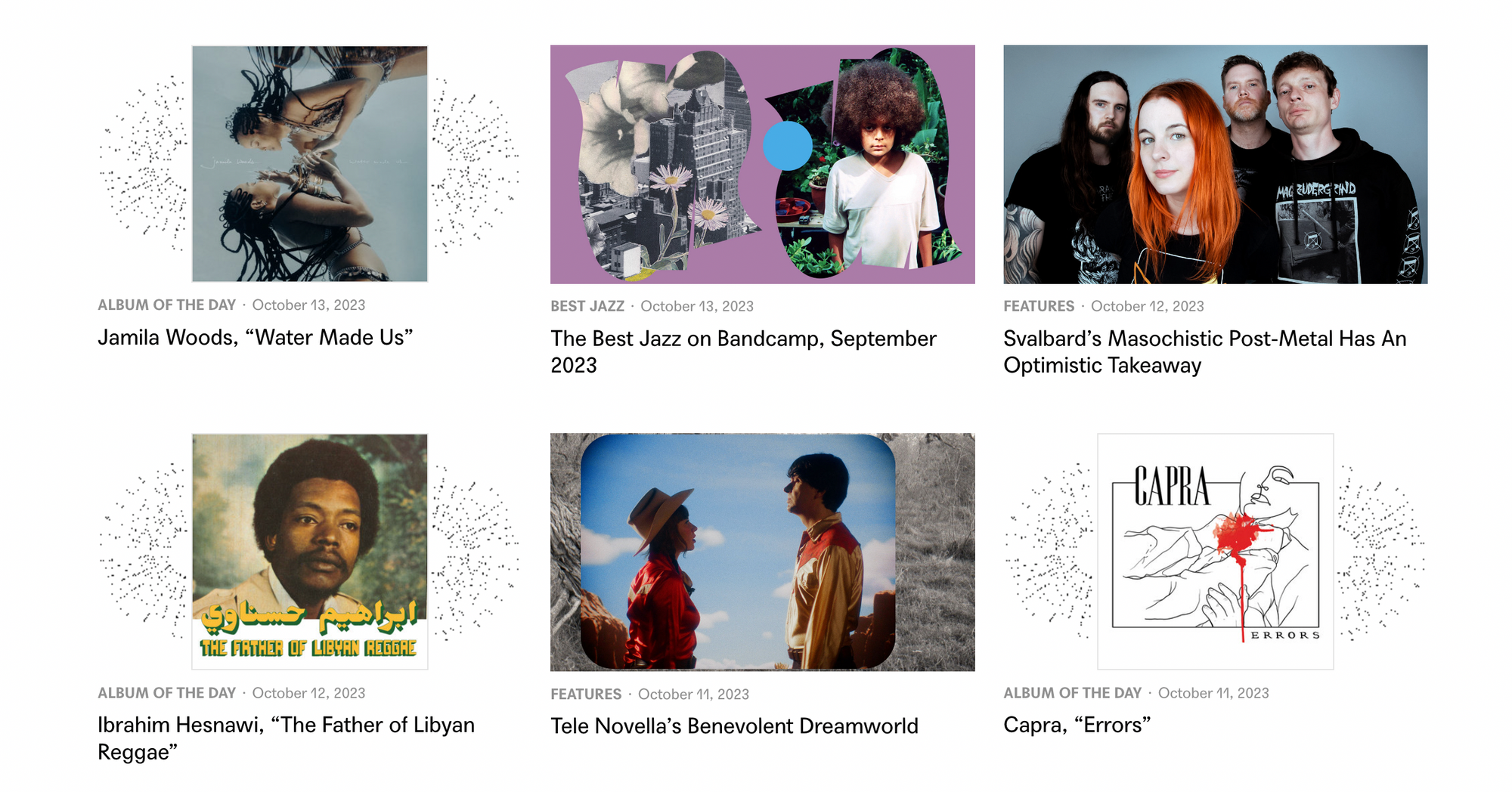

This has been the first blow to Bandcamp’s pretty untouchable reputation. While Bandcamp has always been a tech company, it has also long been seen as a line of defense against the big, bad music streaming services, and has held a culture of its own as a discovery tool for underground, independent music. It is a website that has been able to garner goodwill on all three prongs of its offerings. It’s a music journalism outlet – importantly, that pays – uniquely interested in underground, independent art. It’s a natural extension of the reputation of being able to stumble upon great, independent music via the database of extensively tagged music. Bandcamp Daily has been a beacon of interesting and diverse coverage in a music journalism landscape that is increasingly only interested in finding a way to shoehorn Taylor Swift in wherever they can.

From an artist perspective, the combination of the coverage Bandcamp Daily provides and the nature of the built-in discovery tools has made the site integral to being seen in an increasingly crowded digital world. Upon news of the sale and of layoffs, musicians took to Twitter to give their support to the Bandcamp staff and share their worry about the future due to what Bandcamp has meant to them. New Zealand musician, Lukas Mayo, who makes music under the name Pickle Darling, expressed concern that much of their favorite music “is going to disappear forever” and credits former members of the editorial staff at Bandcamp for all of the traction their music ever received – “no algorithms, just people who loved music and wanted to highlight music they loved, without any concern about how ‘big’ or important the artist was,” they said. Philadelphia indie punk band Gladie credited the platform with being instrumental in their ability to self release their album, Don’t Know What You’re in Until You’re Out, but remain skeptical of what Songtradr will do “to a once beloved community in order to squeeze out every last dollar for its investors.”

Social media is full of endless sentiments bolstering the fact that Bandcamp has achieved a reputation of being a mostly altruistic, artist first company up to this point. It’s hard to overstate just how much good will Bandcamp has been able to accrue. Just like Spotify is trying to be seen as synonymous with the very concept of listening to music, Bandcamp has aimed to be seen as synonymous with the act of supporting artists. And what’s more they’ve succeeded! It’s a convenient service that is seen as the alternative to fractions of pennies per stream and unpredictable algorithms. The refrain is everywhere: Don’t stream music on Spotify! Go buy it on Bandcamp!

Bandcamp has been the reputational beneficiary of an unforced binary born of the era of convenience internet. It is the very rare decent middle man that is providing enough value to the thing people care about – supporting music and the artists who make it – that it’s become the only logical music purchasing option for many people. Fans have built libraries and have been able to feel good doing it. People want to support people who make the art and media that they enjoy. It’s obvious in the rise of OnlyFans and of newsletters helmed by individual writers. What Bandcamp did was make it so easy to feel good about the company beyond being that middle man service. It’s even more centralized than supporting writers through newsletters, as much as Substack would like you to see them as synonymous with supporting writers. The reputation is better than OnlyFans because the platform doesn’t appear to be as much at odds with the people creating the content on the site.

Despite discussions centered so much around editorial staff layoffs and the implications for music journalism, I think Bandcamp should be discussed more like MySpace than it is like, for example, a formerly taste-making site like Vice. This is a story about the cyclical issue with the internet. Bandcamp and MySpace were both built by people who genuinely love music. They have served as universes within themselves where the possibilities of music discovery are endless – it’s easy to search for hours and find new, exciting music within any genre or location imaginable. They have both had curated homepages run by people with deep, earnest connections to music who are hoping to bring ears to the best of what’s available on their respective websites. They’ve both spawned new genres and music scenes, because that’s what happens when that’s where the musicians can be found. Perhaps most importantly, they both have also offered the great promise of the internet – the idea of democratization. This idea that you can skirt the music industry, release whatever you want to everybody in the world directly through this one website, and the people will find you.

It can work. At least until the companies with dubious interest in “music culture” decide it’s not enough to just sustain. The line must go up infinitely. Beloved websites are destroyed by money hungry ghouls everyday. The websites I spent years of my life reading as a teenager desperate to read about music and culture — The AV Club, Gawker, Noisey— existed as hollowed out versions of themselves to different degrees long after they became depressing to look at. Whether it comes down to an SEO click farm, a shell of former infamy without understanding what made it successful, or a slow fade out of anything published at all— they all end up looking the same. They’re graveyards of broken and unreadable articles that changed my life.

Just like all those websites, MySpace was a zombie of itself for a long time before the nails were finally put in the coffin. We know the end of the MySpace saga. Now it’s nothing but a memory of a seemingly better version of the intersection of music and the internet. It’s easy to believe that in 15 years someone will be writing a book mourning the heyday of Bandcamp when it had the power to make real careers and real scenes.

The companies that buy up sites like Bandcamp are interested in nothing except ensuring the executives’ pockets get lined appropriately. Growth is the only thing of interest. It’s the story of capitalism, but here, like with MySpace, it becomes a matter of cultural preservation. They can – and will – ruin everything you love and wipe it from existence. MySpace lost 13 years of music, photos, and videos. We can talk about what was going on on MySpace and interview people who were there, but the data being erased remains an unimaginable culture loss. It’s difficult to even know what has been lost due to the sheer incompetence. Right now there are brewing problems over at resale site and database, Discogs, due to increased fees as a result of a push for growth and in exchange for very little in terms of functionality. The data Discogs has – just like Bandcamp and just like what has been lost at MySpace – is irreplaceable and ever growing. So to have years of culture on Twitter – everything from the continued existence of legacy accounts to the basic usefulness of news organizations being verified – been ravaged by Elon Musk’s vanity. The internet is forever, until it’s ripped away by people who don’t add value to it.

Bandcamp isn’t gone, and maybe it won’t really deteriorate or go away, but it feels as though everybody has come to the conclusion that no website is acting in your best interest – no matter the reputation. No parent company willing to slash half a staff cares about your music community, even if purchasing items through their web stores is still more beneficial to an artist than pulling it up on Spotify. The writing is on the wall, and it has caused a mourning in the broader music community of what Bandcamp represents. Or we thought it represented.

It’s hard, right now, to imagine something that could be able to take Bandcamp’s place because it’s hard to imagine something that will be as usable and as convenient without the money vultures picking it clean. Maybe something will come along – the nature of the internet is that things will be cycled out when something new arrives – but, as of now, I think we may have to just move away from the idea that a convenient service is also going to be a stable, long term home for community.

In Aaron Cometbus’s 2019 book Post-Mortem, the question “what’s left if Gilman Street closes?” is raised. The answer given is easy. The people are left. The loss of the place will be felt, but the people will still be there. Music community in Chicago persists without the Fireside Bowl. Music community in Boston persists without Great Scott. Music community in Philly persists without Everybody Hits. Music culture persists in spite of the corporate overlords who make it harder because it has to. Music community online will persist without Bandcamp or Twitter or Tumblr or MySpace or whatever comes next, but we can’t let it be wiped away completely.

In the meantime download your music libraries and the PDFs of articles you’ve written if you’re a writer. Make your own web stores to sell you art. Pay the people you believe in to write about music. Nobody will preserve the culture you care about for you. Nobody can make it better but us.

Miranda Reinert is a writer, podcaster and zine maker based in Chicago. She can be found on Twitter and her blog, Step One Of A Plan.