The Sublime Terror of Alex Garland

Today an essay on the divisive directing career of the often brilliant Alex Garland and his punishing and kinetic new film Civil War, which I thought was good but not great (and recommend you see in a large and loud theater) despite a lot of the backlash to its supposed lack of political worldbuilding. I've been kind of shotgunning my own scattered thoughts about the film on Twitter and Blusky, none of which amount to anything particularly coherent, but you can look here and here and here and here if you like. Mostly if I were going to suggest it says anything, besides how badly we should not want a war like this to happen here, it would be something I come back to a lot:

In the longstanding battle of pen versus sword the latter seems to be on a pretty devastating winning streak.

The sword is running up the score I'm very sorry to say. I can't even remember the last time the pen notched a victory.

I was on the Flaming Hydra podcast this week along with Sam Thielman, Julianne Escobedo Shepherd, David Moore, and Jonathan M. Katz (which you can listen to for free here). We talked about my recent piece on Weezer, whether zombies can have consciousness, Civil War, and how much everyone seemed to fucking hate Oppenheimer.

Paid Hell World subscribers can stick around for more below by me on some recent news that seems like it belongs in prologue we didn't get much of in Civil War: Tom Cotton encouraging people to assault genocide protestors, the Supreme Court dallying with making protesting itself illegal after declining to hear Mckesson v. Doe, the NYT prohibiting the use of terms like genocide and ethnic cleansing, and USC canceling the speech of their Muslim valedictorian for "safety reasons." Plus the song of the week and an update on the sickly fox I wrote about the other day.

Subscribe to read all that and every other issue of Hell World in full.

The Sublime Terror of Alex Garland

by Erik Sofge

Alex Garland wants you to watch people burn.

In two out of the four movies Garland has directed, as well as the only TV series he’s made, someone is set on fire, and you have to see it happen.

In Annihilation, Garland’s 2018 adaptation of the 2014 novel, Lena (Natalie Portman) watches her husband burn himself to death. In camcorder footage, Kane (Oscar Isaacs), sitting cross-legged against a wall, pulls the pin on a white phosphorus grenade in his lap. He counts down from five. A bright flash blows out the image, then resolves down into a silhouette of a person in flames. The camera cuts to Lena, but quickly cuts back. Kane is clearer now, smoldering in the chemical fire. There’s no mercy in this scene, or the movie. Lena was on a suicide mission to save her husband. Instead, she, and we, get to see him die, in footage recorded before the movie’s main timeline started. Kane is unbothered and strangely inert for someone dying so violently. Like so much of Annihilation, you have no choice—you make of it what you will.

In a GQ interview pegged to the release of his new movie, Civil War, Garland said of Annihilation “I, evidently, don't make commercial films.” This was before Civil War opened to surprisingly strong box office numbers. Surprising because the prerelease discourse around the movie was a derisive internet slog dominated by a collective fixation on the initial trailer’s reveal that the fictional war is between the U.S. government and a coalition of forces from California and—get this—Texas. What an idiot, this Garland, some Hollywood dunce from England who doesn’t understand how red and blue states work.

The largely positive Civil War reviews have done yeoman’s work in dismantling this meta narrative. Never mind that California birthed Ronald Reagan’s political career and with it the modern conservative movement, or that Silicon Valley tech companies and workers are alighting for Texas in droves. But none of that matters to the movie, which eschews backstory or setup of almost any kind. Here’s the thing about Civil War—the movie isn’t doing politics. It’s not here to tell you how bad fascism is. Civil War isn’t agitprop of any kind. Like everything Alex Garland has directed, Civil War has one goal above all else: It wants to make you look at something terrifying.

In Devs, an eight-episode miniseries that ran on FX in 2018, the man on fire is the story’s inciting incident. Lily (Sonoya Mizuno) watches monochrome surveillance footage of her boyfriend, Sergei (Karl Glusman) calmly dousing himself with gasoline. Unhurried, but without hesitation, he burns himself to death. He doesn’t run screaming. Sergei stands for a few moments, his upper body a colorless blaze, then crumples to his knees, then drops onto his side. Lily has to watch it happen. You do, too.

No one, relatively speaking, cared about Devs, a little-watched and barely talked-about miniseries that, while not a movie, supports Garland’s contention that what he makes generally isn’t commercial. Devs is a remarkably weird show, even for the streaming era. From a plot perspective, it joined Silicon Valley in skewering Bay Area tech billionaires years before Musk and the rest made such criticism almost too easy. But while Silicon Valley focused on tech industry dipshits with astonishing accuracy, Devs used science fiction to explore something more malignant dancing in the corners of those gorgeous corporate campuses. Devs even tries to explain quantum computing, with some scenes seemingly showing multiple, parallel versions of an event as it plays out. The show’s tech billionaire (Civil War’s Nick Offerman) isn’t just an asshole. If you get in the way of his pursuit of truly unfettered power, he’ll have you killed.

But more than anything, Devs is terrifying—or at the very least, it’s trying to be. It posits a world where the ability to surveil the past and predict the future is in the hands of a Silicon Valley “genius” with unlimited resources and no accountability. The show is full of death and the uncanny, often jammed together, like the frequent shots of the massive statue of the billionaire’s dead daughter towering over campus. And in the final shot of the series—spoilers, etc.—Lily, the protagonist, is dead. But inside the quantum computing system, a simulation of her reunites with a simulation of her ex-boyfriend, Jamie (Jin Ha). This isn’t the guy whose death kicks off the story, but a previous relationship, the one who got away and is drawn back into her world. But real-world Jamie is dead, too, killed by the company for helping Lily. Devs ends with a simulation hugging another simulation. The hope on their faces means nothing. It’s another horror.

The burning man in Civil War isn’t the protagonist’s boyfriend, husband, or a named character at all. He’s being killed by a mob for unknown reasons, part of a montage of past conflicts that Reuters photographer Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst) has shot. There’s no context or explanation for why it’s happening, though the specific circumstances—a Black man surrounded by a crowd of Black people, a tire jammed over his body to pin his arms while he’s set on fire—recall iconic photographs of an atrocity committed during South Africa’s apartheid period. Visually, it might be the worst of Garland’s immolations. The man is closer, his eyes pleading with the camera for help. The flames spill over his face in excruciatingly slow motion. The camera holds. It’s another horror, and no one is stopping it, and maybe that’s the point.

There’s a temptation for some film and TV viewers that’s relatively unique among artistic mediums—the sense that a movie has to be knowable, or else it’s a failure. Put another way, that every movie has to meet you where you are, instead of the other way around. This doesn’t happen everywhere else. If a painting is abstract, an audience that rejects non-figurative art isn’t that painting’s audience at all. The viewer ignores or dismisses the work. If a song is instrumental, and that’s not your thing, chances are you aren’t weighing in on the composer’s intentions or how that third movement really drags. It’s simply not for you, it’s for someone else, and there’s no debate to be had. And there are countless novels considered too literary, too little about some specific message or devoted to a certain kind of entertainment mission, for some audiences to bother consuming, much less generate an opinion about.

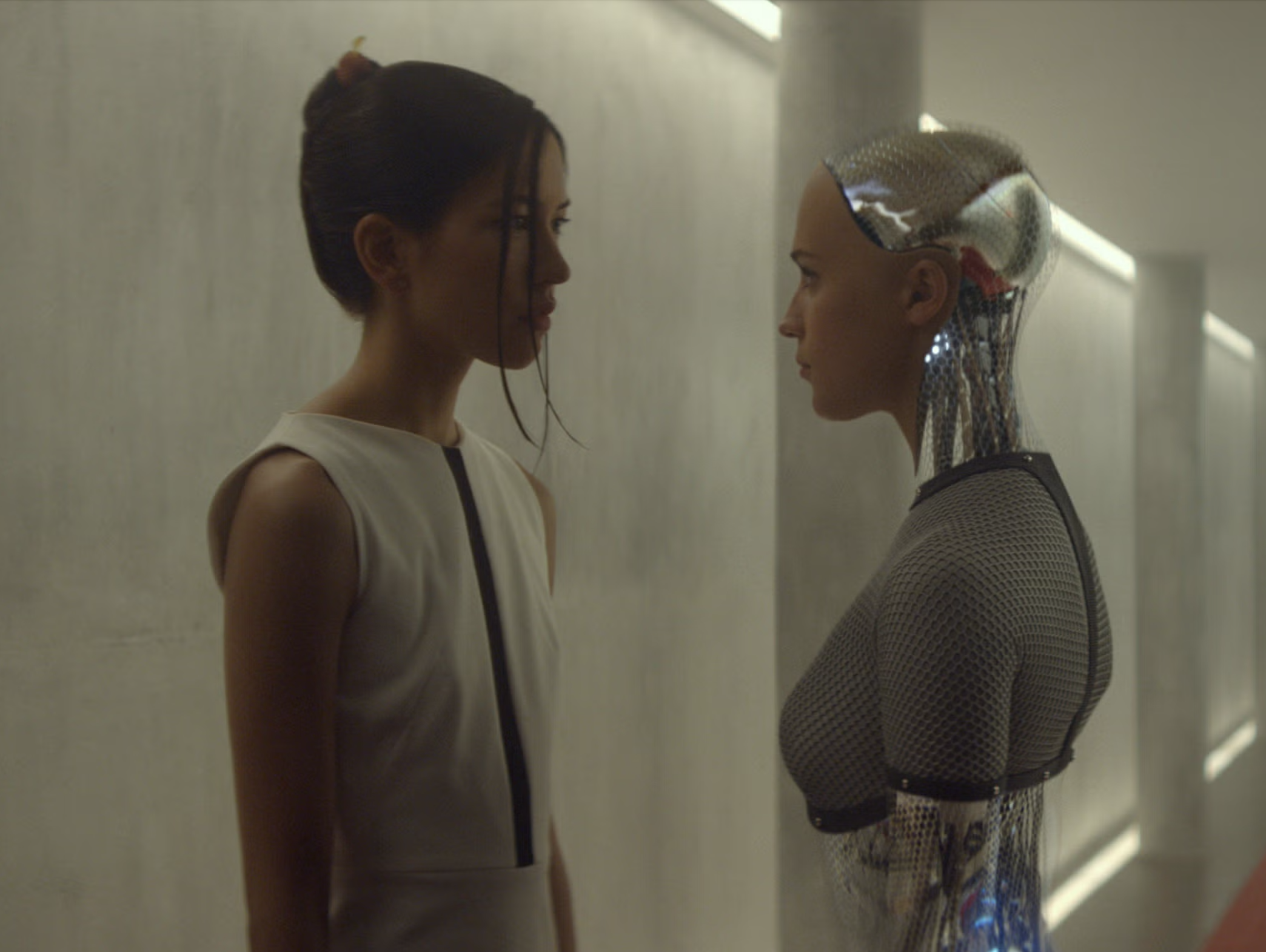

But movies and TV are different. Especially now, and especially the kind of genre narratives that Garland used to direct—I say “used to” because Garland has said he’s done directing, at least for a while. His movies are filled with neat sci-fi bells and whistles, from the beautiful killer robots of his directorial debut, Ex Machina, to the amalgamated monster in Annihilation that wails with its last victim’s voice, to the darkly thrilling sequence in Civil War where tanks, gunships, and soldiers tear through Washington D.C. Those genre touches must mean these movies are confections, to be consumed as part of a constant, 24-hour buffet of content rolling down the conveyor belt. If some aspect of it isn’t to your taste, or worse still, isn’t what you expected, someone in the kitchen must have fucked up. After all, if this fool didn’t know that Californians universally hate Texans (and vice versa), he must have also forgotten to clearly villain-tag the bad guys in every scene, or to have a character exasperatedly review all of the events that led up to the civil war, while the audience nods in awe at the depth and complexity of the worldbuilding.

It’s no use complaining about the primacy and mainstreaming of geek culture, and how it’s turned any discussion of the difference between art and entertainment into an assault on people’s preferences. What’s done is done, what’s dead is dead. But as Garland’s directorial career apparently ends, on what looks like a commercial high after a string of box office and ratings bombs (Annihilation, Devs, and 2022’s Men), his body of work raises the kinds of uncomfortable questions that few directors manage in careers five times as long. The best of those questions are existential in the most literal sense, worth asking because they’re impossible to resolve. But here’s one that, like so many of Garland’s horrors, I can’t seem to shake:

Why in the world would anyone think art is supposed to have answers?

No one burns to death in Ex Machina, the 2014 movie that seemed to announce Garland’s arrival as not only an accomplished screenwriter (28 Days Later, Sunshine), but now a talented director. It was also the beginning and the end of anything like a consensus about Garland. Everything he’s directed since has drawn such descriptions from critics as “muddled,” “uneven,” and a “mess.” The Atlantic’s review of Annihilation called it “A Beautiful Heap of Nonsense,” adding that it “lacks structure and coherence.” Slate deemed Devs “bad television that’s striving to be great” and “a philosophically minded, prestige sci-fi cock-up.” Pushback came to a head with Garland’s Men, a pandemic-production horror film with a 69% score from critics on Rotten Tomatoes, and a 39% score from audiences. Some, to be sure, celebrated Men. But the knives that came out for Garland’s most experimental film were sharp indeed. Vanity Fair’s review asked “Is Men Necessary?” The Independent bemoaned Men’s “hopeless perspective” after what the reviewer saw as Garland’s apparently upbeat previous two movies. “The former [Ex Machina] ended with Alicia Vikander’s android ready to integrate herself into human society. The latter [Annihilation] saw Natalie Portman’s scientist make peace with life as host to an alien anomaly.”

It’s objectively funny to dig through the nightmares that Garland puts on screen in order to find something—anything!—feel-good in the climaxes of Ex Machina and Annihilation. But there’s value in those perverse interpretations. They reveal what Garland was doing across 10 years of directing, and why his decade of work has been so divisive.

For many audiences, lots of critics included, the only thing that really matters is the story. This is the triumph of the Hollywood model, where every frame, every word, every needle drop, every measure of score, and especially everything an actor does, is all in service to the story. The story, to be clear, doesn’t need to be original. If anything, it’s often easier if it isn’t. It just has to hit the beats the audience expects, keep the pace nice and steady, until boom, here comes the twist!

At its best, the Hollywood model leads to movies that are muscular, propulsive, and other cool descriptors for art as nothing more or less than a strong guy. Above all else, the Hollywood model has no time for weird shit. Like, for example, the end of Ex Machina, five minutes of dialogue-free visuals, as the score from Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow (the composing team that’s worked on all of Garland’s movies, as well as Devs) slides from lilting xylophone into a thrumming roar. Then, two words of dialogue (“Ava! Ava!”) and no more talking for the rest of the movie, roughly three more minutes of ambient noise, and the xylophone coming back in, as Ava leaves the man who loved her to die.

With each project after Ex Machina, Garland pushed harder, away from the Hollywood model, into territory that is frankly confusing for genre films. Annihilation’s climactic scene features dance choreography, and an electronic score so unmoored from reality you’d be excused for thinking it’s alien dialogue without subtitles. Men’s ending is almost indescribably strange, a paroxysm of gore and reproductive horror that nearly convinces you the entire movie must have been the protagonist’s delusion, until her friend shows up the next morning and sees the bloody evidence.

Civil War’s departures from the standard mode are more subtle, and easier to interpret as mistakes or a loss of nerve. The movie’s president is clearly a fascist—we’re told his government shoots journalists on sight. But Civil War doesn’t spend a single frame championing the virtues of journalism. Like the rebels pushing toward D.C., its subjects just want to be there when it happens. In the end, their presence arguably creates more bloodshed, not less, and does nothing to make sense of the chaos. They get what they want, though: to bear witness to horrors.

But those are story elements, and focusing on them misses what’s made Garland distinct as a director. Civil War isn’t a vessel for its story, which is so spare it could be relayed in a few sentences. It isn’t withholding worldbuilding or characterization details by accident. Those details do not exist in the movie. There’s no lore to unpack on Reddit, no narrative puzzle to be solved. There’s no explanation, no solution, and no answers.

Instead, there are visuals and sounds. In Civil War, there are Hawaiian-shirted boogaloo boys executing soldiers to De La Soul, and Jesse Plemons’ war criminal in jaunty red plastic shades, his gunshots pushed louder in the audio mix than any gunshots you’ve heard in a movie theater this decade. There’s Men’s image of a man bracing himself against a doorframe as legs protrude from his mouth, the audio of wet, irrational biology accompanied by a single, distorted choral vocal run. There’s the gorgeous fungal tableau of Annihilation’s exploded swimming pool corpse, and how the movie’s score dissociates over time, plaintive acoustic guitar riffs giving way to distorted, amelodic buzzing and howls that blur the line between score and sound effects, and that other film and TV composers have scrambled to imitate.

If all you care about is story, almost none of what Garland did as a director is interesting. In that context it’s style obscuring substance, or worse, style because he made movies but presumably forgot to add substance. But if Garland just wanted to tell crackerjack stories, he could have kept doing that as an in-demand writer, one of a select group of screenwriters whose name anyone outside of the industry knew. Instead, for 10 years, Garland made movies and TV whose sights and sounds bear strange, often impossible questions, and no answers. They just want to show you something horrible.

Erik Sofge is a Senior Editor at MIT Horizon. He’s written for Slate, Popular Science, and Men's Journal.

In an interview on Fox News senator Tom Cotton suggested that people who are inconvenienced by anti-genocide street protests – like those in San Francisco and Chicago this week – physically attack the protestors and throw them off of bridges.

Subscribe to read the rest.