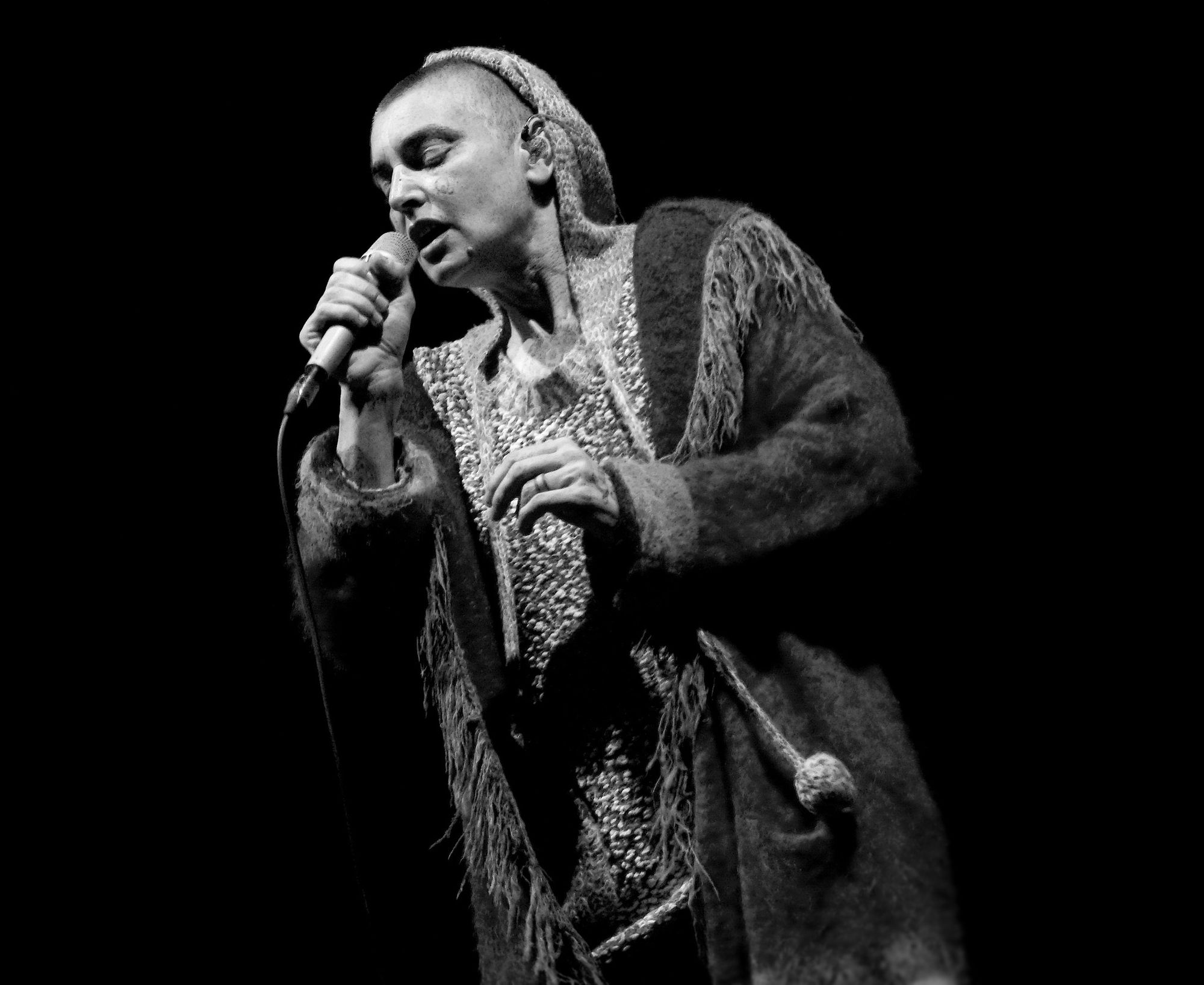

The Fury of Sinéad O'Connor

It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society

Please consider a free or paid subscription to Hell World. Your support is appreciated.

It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society

by Leila Brillson

There's millions of people

Who offer advice and say how I should be

But they're twisted and they will never be

Any influence on me

-The Emperor’s New Clothes

The Year of the Horse is a little secret I keep. Every now and then I’ll throw the 1990 concert on in a silent room when nothing else is happening. One by one disparate members of my household will slowly congregate around the TV, where a 24-year-old Sinéad O’Connor has taken the stage. Fascinated, awestruck, some don’t know who they are watching. Others ask about the intense bald chick. How old is she? When was this? Was this before or after the “incident?”

Before of course. No one would have invested in a concert video of this quality after she so thoroughly declared war on such a powerful entity as the Catholic Church. Not back then anyway.

The reason it engrosses so thoroughly, its gravitational pull, is because of how raw O’Connor is. An exposed nerve, without even tresses of hair to hide behind. She flails and howls, whispers and shrieks, accuses and repudiates. It’s oddly sexy and undeniably dangerous.

I’m unsure how it happened, but this concert movie became a childhood companion, calming me before bed, or giving my parents a sixty minute reprieve while I sat mesmerized. We had it on VHS, and I would, as a small child, be drawn to this strange siren who seemed so angry. So furious. The Last Day Of Our Acquaintance taught me the word for people who aren’t quite friends. When she sings “You used to hold my hand when the plane took off,” I related because my dad did the same thing to me. (I was seven, if that. I also wrote a cover of Nothing Compares 2U called Nothing Compares To Cat Food.) I have no idea how we came to own that VHS; it was the only live recording my household had besides Stop Making Sense. Kids like things that feel epic, huge, easy to hold and larger than life, and her massive voice filled a room in a way that is nearly tactile.

She also did an Irish jig, which is fun.

I am not a Sinèad O’Connor historian, just a super fan. I dropped out when she started doing reggae and world music, just because she wasn’t delivering those gut-wrenching ballads of her earlier years, that one-two punch of her debut and sophomore albums. But I was irrevocably changed by those records, her story, her absolute unwillingness to be a pawn in an industry that always has a marketing plan for a woman before they even have an album started. So I remained a vehement defender whenever she was called a one-hit wonder, and someone who tries to point out, look, this is what we do to women who are angry.

Until the philosophy

Which holds one race superior

And another inferior

Is finally and permanently

Discredited and abandoned

Everywhere is war

-War

Even from the beginning, Sinéad O’Connor had a patriarchy-sized target on her back. She was a young, unwed mother, from a country roiling with political turmoil. She was poor. She was "bad." Her behavior as a teen got her sent to a Catholic asylum—which is where she learned to hate Catholicism, and she learned she had those pipes.

She also learned, first-hand, what Catholic institutions did to young women.

“It was a prison. We didn’t see our families, we were locked in, cut off from life, deprived of a normal childhood,” she said of her time at the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity laundry in Dublin.

“We were told we were there because we were bad people. Some of the girls had been raped at home and not believed.”

Later she got in with U2, until she loudly supported the IRA. Her 1997 song This is A Rebel Song is believed to be a rebuke of the much more famous, more palatable band.

On top of all of that she was bald. This was a reaction to the expectations of femininity that fall upon all young women in general, and pressure from her own mother in particular, but also to the music industry at large.

“They wanted me to grow my hair long, wear short skirts and high heels and makeup and write songs that wouldn’t challenge anything,” she said years later, still shaving her head.

“I wasn’t going to have any man telling me what to do, or who to be.”

And despite—or maybe because of—being Sinéad O’Rebellion, she was extremely horny. She wore combat boots, ripped denim, and no makeup, and sang about being touched, wanted, craved in visceral and direct language. The first time she played in the States (on David Letterman) she performed Mandinka (an example of her range and power), but the extremely graphic I Want Your Hands On Me was really her bigger hit, a song about the urgency of desire. She flirted on stage. She fell in love hard. In her memoir she wrote “I have four children by four different fathers, only one of whom I married, and I married three other men, none of whom are the fathers of my children.” She would not let you forget her sexuality, even when she actively defied all its classical signifiers.

So already she was a powder keg, a scion of controversy—having already boycotted the Grammys because they are capitalist bullshit—when she walked onto the silent SNL stage in 1992, at the height of her fame. (She asked that the “applause” sign be turned off for dramatic effect.) When she did what she did, for the abuse she suffered at convents, for the way Catholicism tore her country apart—it wasn’t just a scandal. She became an untouchable pariah, dooming her career and effectively making her (to the public at large) a one-hit wonder.

The whole world hit back. Madonna (whose Like A Virgin pales next to I Want Your Hands On Me) mocked her. Joe Pesci, when he hosted SNL the next week, suggested he’d have hit her, and the crowd cheered. Disgruntled Catholics rented a steam roller outside of Rockefeller Center to crush her albums. A few weeks later, after a non-stop blitz of bad press, the 26-year-old was so loudly booed by the entirety of Madison Square Garden, she gave up trying to perform and just scream-shouted the lyrics to Bob Marley’s War into the mic and walked off. She was never given a platform that large again.

These are dangerous days

To say what you feel is to dig your own grave

Remember what I told you

If you were of the world they would love you

-Black Boys On Mopeds

Turn on The Year of the Horse. Watch her perform Troy, eschewing the melodrama of the cellos and band for an acoustic guitar and a spotlight. Hear her voice seethe, the range of the a capella, the way she calls the unseen subject a liar with dripping vitriol. Her fury booms out of her in a mezzo soprano range.

Sinéad O’Connor was born to a woman who abused her, grew up in a country that abused women, and then suffered abuse that only a woman could endure. She was not well, attempting suicide for the first time in 1999. When her own young son took his life in 2021 she promised to follow. She had fibromyalgia. She had bipolar disorder. She changed her name several times. Her politics were messy and often problematic, and as she sank into her newly found Muslim faith she made some regrettable comments about non-Muslims (that she soon retracted.) In a reactionary move, she even slut-shamed Miley Cyrus and her wrecking ball.

So for the last decade, she was “a woman in crisis,” while simultaneously being vindicated for her “original sin” as more and more clergy sex scandals piled up. But she was never, ever given an apology. She was never honored or celebrated. She was no longer filled with fury, but sadness and despair.

“It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society,” she commented on a story about herself in the New York Times in 2021.

Gen X is angry, its members disillusioned by the safety promised by their Boomer parents. In fact, Gen X is angry at everything. But Sinéad, she was angry at something. She could see it clearly, sitting in front of her, a part of her everyday life: injustice and abuse. On I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got, she sings about Black Boys on Mopeds, calling out Margaret Thatcher for being more outraged at crises outside of England than horrified by the police murder of a boy who was accused of stealing a moped that was his own. Like tearing up the picture of the Pope, this fury was oddly prescient, bubbling up in the back of her powerful throat.

Sinéad O’Connor’s cause of death has not been revealed. I have no interest in speculation. But she was a woman who was failed again and again and again, by men, by her own health, by religion, by the music industry. And she kept getting up and getting angry. So perhaps, hopefully, she can find some peace now, a phoenix from the flame.

I will rise

And you'll see me return

Being what I am

There is no other Troy

For me to burn

-Troy

Find more from Leila Brillson at her newsletter Night Creeps.

Please consider a free or paid subscription to Hell World. Your support is appreciated.

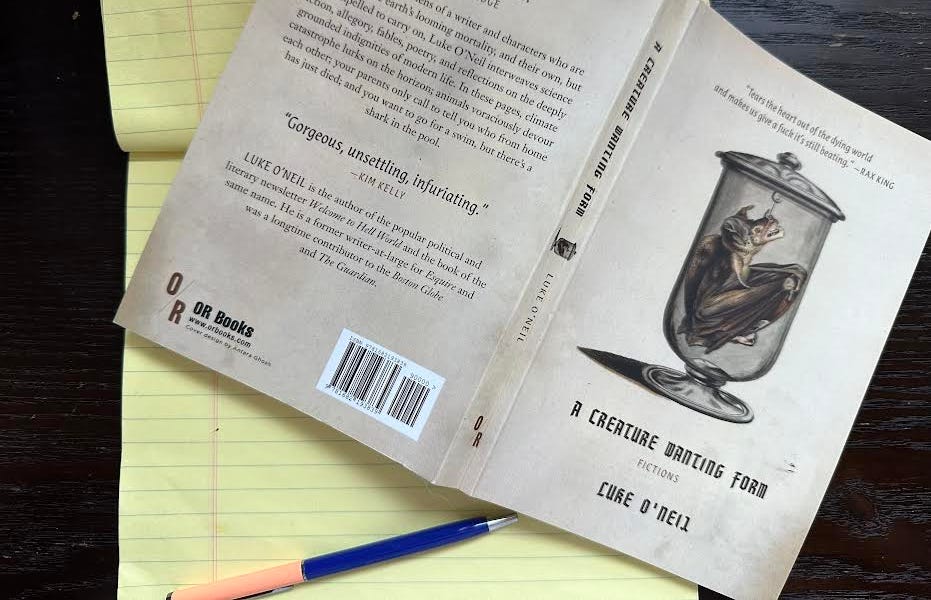

Thanks to Jason Diamond for the thoughtful piece on my book A Creature Wanting Form.

Here's an excerpt:

O’Neil’s book is also strange. I say that with all the respect in the world. I mention my longstanding fandom reading his “Welcome to Hell World,” one of the first newsletters that ever became a regular part of my media diet or whatever the hell you call reading stuff online all day. You get unflinching honesty when you read O’Neil’s stuff. The world is dark and full of terrifying people with horrible intentions, and O’Neil has made a place for himself by exploring all that in a way that’s engaging but also doesn’t make the reader feel like a dummy. Part of it is O’Neil is removed far from the media world of NYC or the Beltway drama of D.C. (well, he’s in Boston, so maybe not that far in terms of mileage) but I also think it’s because he’s got that punk/DIY training, so instead of feeling like you’re reading something handed down from a skyscraper in the middle of a big city, it’s more like being at a basement show and the band is telling you to crowd closer to them. There’s an intimacy about it, and the real emotion that comes through. O’Neil is a writer, journalist, commentator, editor, publisher, or whatever he wants to call himself. But he’s also a human, and the things he’s writing about, I have to believe, trouble him deeply.

That’s what interested me about his book of fiction. It’s not a novel. O’Neil can write as somebody else if he so wishes using that form. I suppose you could say it’s short stories or vignettes, but I don’t want to mislead anybody with labels. Some of the stories take up a quarter of a page, while some of the stuff could be filed under poetry or allegories. One, for instance, “To the Ground,” is a meditation on an ant crawling across a porch that ends with the line “When it’s expected of you to work yourself to death maybe exhaustion isn’t even a concept.” It’s a neat little trick he pulls in maybe 200 words or so, putting us in the shoes of somebody watching an ant, something we can literally walk outside right now and probably do, then giving it deeper meaning. The lesson is that there can be something taken from anything. The world is terrifying, but it’s also filled with wonders and lessons. The problem is humans take those wonders for granted, and we’re actively doing all we can to ruin what we’ve been given.