No New Women’s Prisons

"I was under the impression that we all end up in prison"

Today Bill Shaner reports on an anti-incarceration march in Massachusetts organized by Families for Justice as Healing among others. In April he reported for Hell World on the (still ongoing) strike by nurses at Saint Vincent Medical Center. He writes the newsletter Worcester Sucks and I Love It.

Please chip in to help pay for great reporting on under-covered topics like this if you are able to.

No New Women’s Prisons

by Bill Shaner

If you can look past the inherent cruelty it’s a simple question of math.

A woman in prison costs the state about $100,000 a year. There are, give or take, 135 prisoners in MCI-Framingham, the only state-level women’s prison in Massachusetts. So back of the napkin we’re at about $13.5 million a year.

The state is considering spending $50 million to construct a new prison for these women, where they will continue to cost the state $13.5 million a year, only somewhere else. Somewhere cosmetically different.

What’s the point?

That’s the essential question asked by a coalition of abolitionist and prison reform groups which yesterday embarked on a statewide march in support of proposed legislation to put a five-year ban on all new prison construction, effectively spiking the construction of a replacement for MCI-Framingham.

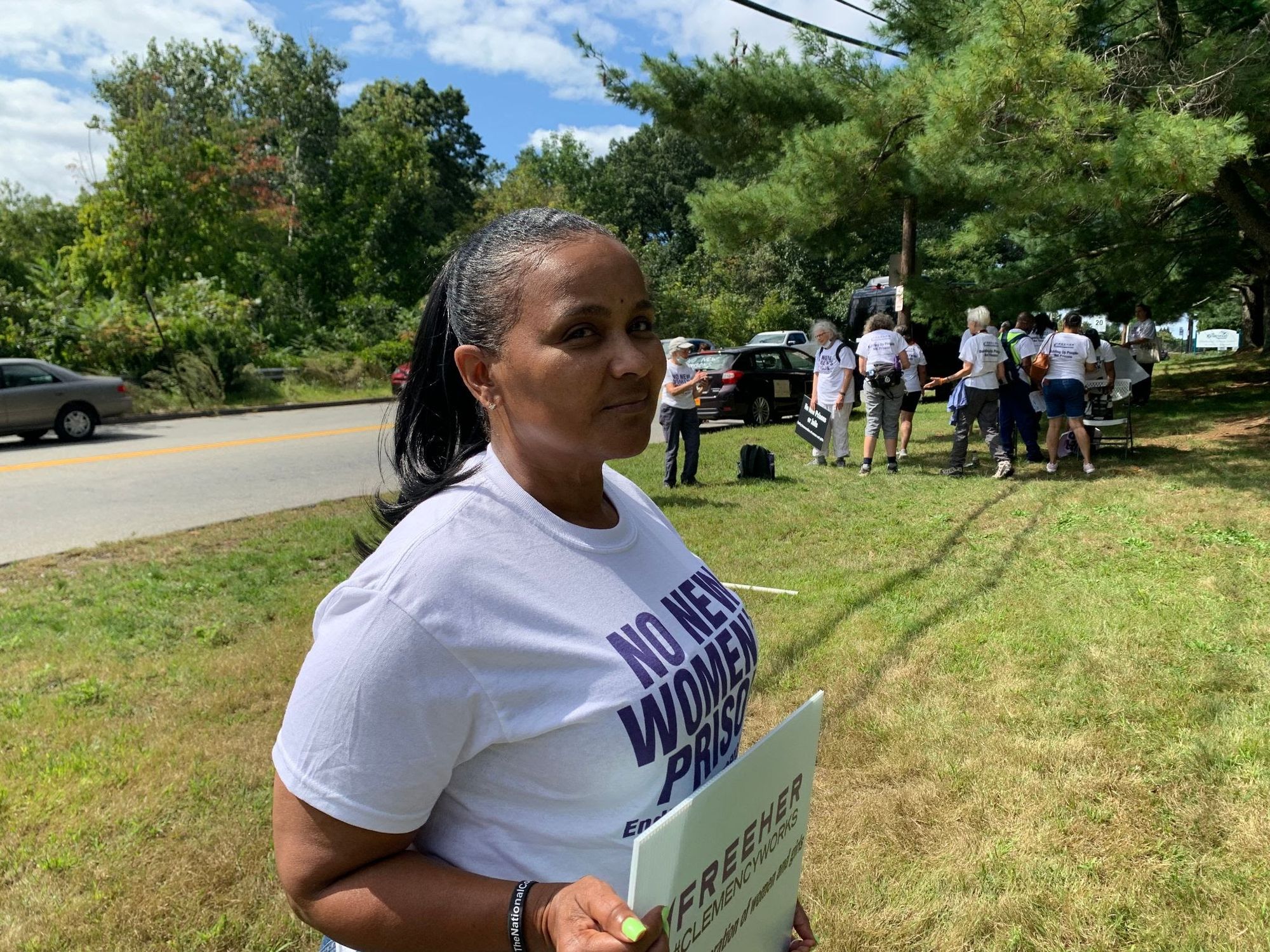

They began yesterday morning in Worcester with a rally outside the courthouse. Then they embarked on a six-mile march to the Worcester House of Corrections, a county jail tucked unassumingly in a woodsy suburb just outside city limits. I caught up with the group halfway through the march and found them stopped on a patch of roadside grass for a break. Several dozen demonstrators held signs and waved to a steady line of passing drivers in mid-day traffic. They all wore white shirts sporting a message in bolded all-caps and purple font reading “No New Women’s Prisons: Ending Incarceration of Women and Girls.” Songs of freedom and abolition and also Walk on The Wild Side at one point, because why not, blared from speakers in the back of a pickup truck.

The march is the brainchild of Andrea James, a formerly incarcerated woman and the executive director of the National Council for Incarcerated Women and Girls, as well as the local organization Families for Justice as Healing. Since her release from prison in 2011, James has made the decarceration of women her life’s work.

“We’re here to say that the last thing we need in Massachusetts is another women’s prison. We have one of the lowest incarcerated populations in the country,” James told me during one of the few moments she could step away from organizing the march. “We have 135 women in our state prison. And we should be creating what ‘different’ looks like.”

Indeed Massachusetts’ female incarceration rate is well below a national standard that is, by measure of the rest of the world, egregious. A 2018 study by the Prison Policy Initiative found that the U.S. accounts for 30 percent of all the world’s incarcerated women, despite having just 4 percent of the world’s female population. The female incarceration rate in the U.S. as a whole is 133 women per 100,000, according to the study. It’s the highest rate in the world, followed by Thailand, El Salvador, then Russia. By state Oklahoma has the country’s highest rate at 281 per 100,000. Twenty six states have a higher female incarceration rate than any country in the world. Massachusetts’ on the other hand is just 40, higher only than nearby Rhode Island’s rate of 29.

Massachusetts’ relatively low population of incarcerated women is exactly why James and company feel it’s so important that the state not invest any more money into new prisons.

“We’re not a California. We don't have 1,000 women just in one prison,” she said. “Total, if you throw in the county jail sisters, we've probably got 500 women in a cage somewhere. If we can't figure out what different looks like and be a model for the rest of the country, with apparently what is millions and millions of dollars that they have to spend on this, then shame on us. And that’s why we’re here.”

As I spoke to James some passing drivers honked and cheered for the demonstrators. The driver of one car honked more emphatically and for longer than the others, so much so that I drifted away from the conversation to take a look. There was a young white woman in the passenger seat, visibly in the middle of a red-in-the-face hard cry. She looked at the demonstrators and nodded her head slowly in approval, tears streaming down her face. Perhaps, I thought, she was on her way to the Worcester House of Corrections, just down the street, to pay someone she loves a visit. Someone who’s been there too long. Someone who could have benefited more from a different approach to justice and restoration.

It was the start of the “The Long March for No New Prisons and Jails in Massachusetts,” a weekend-long event in opposition to the construction of a new women’s prison. Today demonstrators held a press conference outside MCI-Framingham, the only state prison for women in Massachusetts, and marched from the prison to Wellesley Town Hall. Tomorrow, the march picks back up on the Cambridge Common at 10 a.m., and at noon they’ll set off to the Suffolk County Jail for a 4 p.m. standout in memory of Ayesha Johnson and Rashonn Wilson, who both died in custody at the South Bay Jail. On Monday, the demonstration culminates in a march from the Suffolk County Jail to the Massachusetts State House for an 11:30 a.m. rally in support of the legislative push for a moratorium on new prison construction.

The legislation is called “An Act Establishing A Jail and Prison Construction Moratorium” and it was filed in late March. If passed, the measure would prohibit the creation of any new prison, any expansion of capacity in existing prisons, or the reviving of any dormant facility. Basically, it would bar any sort of spending on anything besides the maintenance of existing prisons for five years.

For the past several years, state officials have targeted MCI-Framingham for demolition, saying it’s old, dilapidated and beyond saving. They want to rip it down and build a new shiny prison, to the tune of about $50 million, in Norfolk, on the footprint of a former men’s prison called Bay State Correctional Center. Right now, the center is used only as office space for Department of Corrections employees.

In 2019, the state started seeking bids for the design of a new women’s prison with the goal of moving prisoners by 2024. An inspection from that year found dozens of violations at the Framingham facility, including shoddy plumbing, dirty kitchens, moldy and rusted showers, rodent droppings and a lack of toilets, among other things. The prison, opened in 1877, has fallen into a state of obvious disrepair, or such was the takeaway of the Department of Public Health inspection. The state tasked potential contractors with a design that sets “a higher standard for women’s correctional centers.”

This April the DOC chose the architectural firm HDR for the project after a three hour presentation followed by brief public comment in which abolitionist activists were roundly ignored. HDR is a national architectural firm with a long track record of designing prisons and courthouses, and promised a prison which offers “trauma-informed care” and “an environment with natural light, access to views of nature, normalized furnishings and finishes, in addition to soothing colors [that] can help reduce anxiety, fear, anger, and depression,” according to its proposal.

All of the people I spoke to at the march yesterday scoffed at the idea a prison could adequately provide “trauma-informed care.” When I asked James about the idea, she launched into a heated rant. The culture of incarceration—from the trappings of the system itself to the attitudes of the guards to the simple psychological diminishment of confinement—do not change with a new building, she said.

“We know there’s no such thing as a ‘trauma-informed prison,’” she said. “They want to paint the walls pink. They want to put in gardens. They want to increase the time that children spend in prison with their mothers, and we're like, ‘Hell no.’ First of all you're talking about our children. You're talking about the same families from the same communities. You're not talking about shifting and looking for people from Newton to lock up. And so you're not going to build a new prison for our daughters and our granddaughters to land in. And you're certainly not going to indoctrinate our children by allowing them to spend more time in a prison.”

When James says “our,” she means Roxbury. It’s where she’s from, and it’s where most of the activists at the march were from. She called it the most heavily incarcerated corridor in the state, so much so that parts of it made it onto the landmark 2012 “Million Dollar Blocks” study of poor neighborhoods ravaged by the criminal justice system and constant cyclical incarceration. What Roxbury and neighborhoods like it need is fewer police, less criminalization, and more resources, she said.

“We know that it’s been a level of austerity in investment in our communities. And what they've done instead is invest in police and in prisons,” she said.

Stacey Borden, another demonstrator, aims to do the opposite. She launched New Beginnings Reentry Services, a Dorchester-based home for women reintegrating into society after prison time. Borden herself spent the better part of 30 years in MCI-Framingham and is now a licensed clinician and trauma specialist.

“I was in and out of Framingham for years and I owe it to the sisters back there to bring them home,” she said.

Via partnerships with local non-profits, colleges, and the public schools, New Beginnings aims to offer a way out of the criminal justice system and, ultimately, a model for how to rehabilitate people without it.

“We want to build the women up to go back into the community and bring the resources that our community needs and deserves. Because we know we're most directly impacted. That's it.”

James and Borden both approach the issue from an abolitionist framework. In their ideal world the prison as we know it does not exist, replaced by a more humane, just and effective system. And they work in tandem.

“I met [James] back in 2012 and I said ‘you get ‘em out and I'll keep ‘em out,’” said Borden. “It’s my job to keep them out.”

Both talked at length about how $50 million could be better spent than on a prison building that simply replaces an old one.

“That $50 million should be going to those community-based programs that are directly impacted,” said Borden. “And we could do a lot better to serve women, allowing them to heal outside of a prison and inside a community.”

The perception that prisons do not—and categorically cannot—rehabilitate inmates for a healthy life on the outside was at the forefront of the minds of everyone I talked to. But perhaps none more so than Danielle Metz, a New Orleans resident who flew up to accompany Jones in the demonstration despite a home left in shambles by Hurricane Ida. Metz, who spoke with a thick bayou drawl, spent most of her adult life in prison, sentenced to three life sentences on drug charges when she was 26. Through the advocacy of James and others, she received clemency from the Obama administration in 2016. Now, a free woman, she lends herself to the cause when she can.

“You know, I'm free but I'm not free until they're all free,” she said. “Because you sort of have survivor's remorse.”

Like James and Borden, Metz scoffed at the idea a prison could be designed to be more humane and more sensitive to trauma.

“Nothing you can put inside of a prison to me can be ‘trauma informed,’” she said. “It’s almost like you have PTSD when you come home because you've been through a traumatic experience in prison. So you can’t build that in a prison. Why can’t we build that in the community?”

As of yet, the bill to ban new prison construction hasn’t really gone anywhere. Sponsored principally by Northampton State Sen. Joanne Crawford and Roxbury State Rep. Chynah Tyler, it’s been referred to a subcommittee and was scheduled for a hearing in July. But that’s it. There’s been no significant action to bring it toward a vote. Still, the bill enjoys a fair amount of support: Twenty-eight state reps and 22 state senators have signed on to support the measure. But it’s entirely possible the bill could go the way most bills tend to go in the state legislature, to languish in subcommittee and die a slow, quiet death.

When it comes to why the state is pushing so hard to replace the prison, James is deeply skeptical of Governor Charlie Baker. Throughout our conversation she often pondered why now, and why this prison?

“This man is just intent on moving ahead like a steam engine in building this prison,” she said. “We can only chalk it up to he owes people favors and this is how he'll start to repay the favors before he decides what else he wants to do with the rest of his life. But he's not going to do it by building a prison that kids in my neighborhood could potentially land in when we have much better ways.”

As we walked to the Worcester House of Corrections, where we’d be greeted by barbed wire, heavily armed guards, a drone overhead, and disconcertingly friendly prison brass, I talked at length with James’ daughter Sashi, who marshalled the march and took pictures. Both her mother and father had spent time in prison and I asked her what it was like, growing up with incarcerated parents.

“Well I didn't know what Father’s Day was until I was about twelve and then when my mom went to prison I was headed to college, I was a little bit older, and I was also under the impression that at the end of the day we all end up in prison, so I thought that it was just my mom’s turn, and then eventually I would be in prison at some point,” she said. “But I didn't understand that really we were under a system of oppression until my mom came home.”

Bill Shaner used to work at an alt weekly called Worcester Magazine but it was bought by a media conglomerate and destroyed so now he writes a newsletter called Worcester Sucks and I Love It.