Mama I’m Coming Home

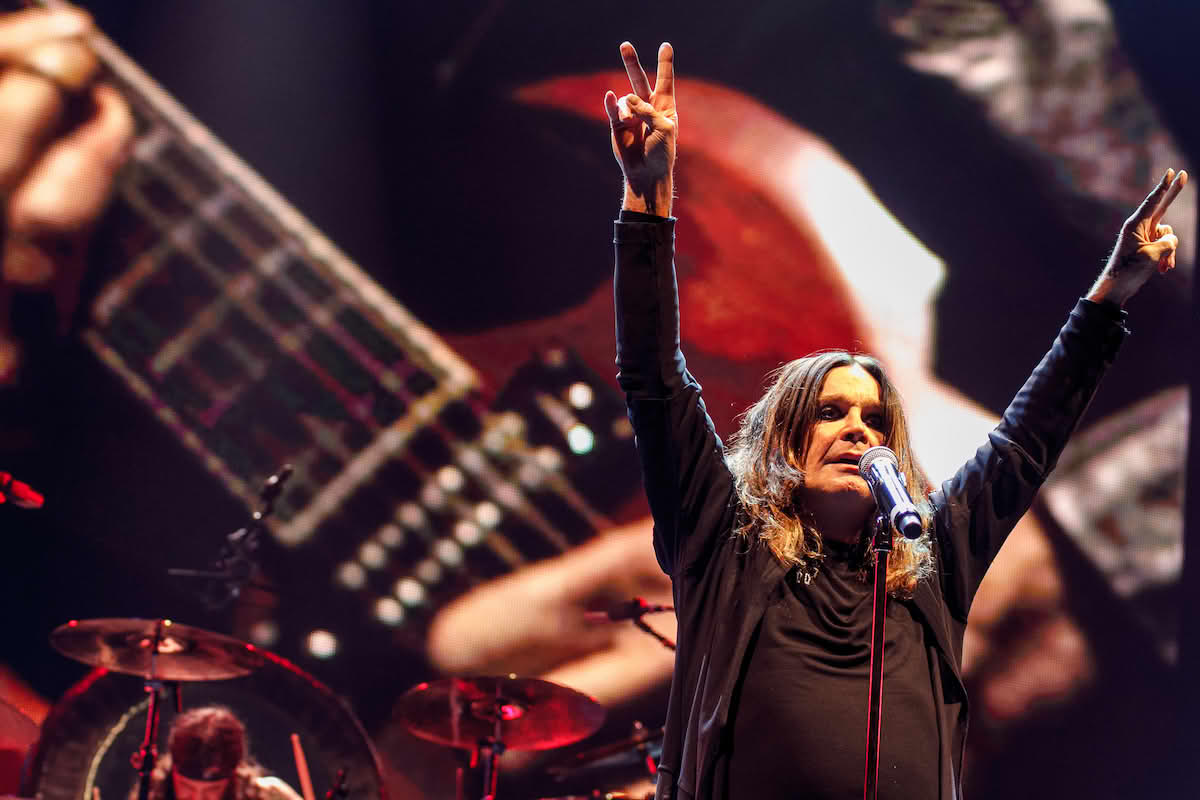

Two weeks ago I was sitting in the very spot where I sit now crying my eyes out. Not exactly out of the ordinary for me but nevertheless. M. asked what was wrong and I said I was watching Ozzy sing Crazy Train. Did he die she said and I said no not yet but I had the sense I was mourning his passing in advance. Also the feeling that he would never die.

So too was I mourning my grandfather – who like Ozzy died of Parkinson's – and my uncle who may well die from it some time soon.

Ozzy didn't look well – and he of course was not – but he pulled it together to belt out the hits one last time for tens of thousands in his native Birmingham and millions more watching at home.

Dave Wedge joins us today to write about Ozzy's legacy and his experience of interviewing him over the years. Wedge's new book Blood & Hate: The Untold Story of Marvelous Marvin Hagler’s Battle for Glory – about another working class hero – is available here.

Also today Del Winters traces the evolution of how films from the 1970s through today reflect our collective anxieties under capitalism over land seizure, gentrification, consumerism, worker alienation and isolation and more.

Read it here or down below.

If you're the protagonist of these movies, the person ruining your community is known to you. At your moment of triumph, you can tweak them on the nose or riddle them with bullets or rip up their foreclosure documents because they're there, physically, in front of you. As corporations snapped up more and more land and strip malls emerged as the dominant suburban life form, movies where neighbors and friends came together to save the town occupied less and less of the pop culture milieu. The fight was lost, and by the next decade a new villain had emerged, this time in the mirror.

As you know it costs money to pay for the writing and reporting we do here at Hell World so please consider a subscription if you have the means to do so. Here's 25% off one year.

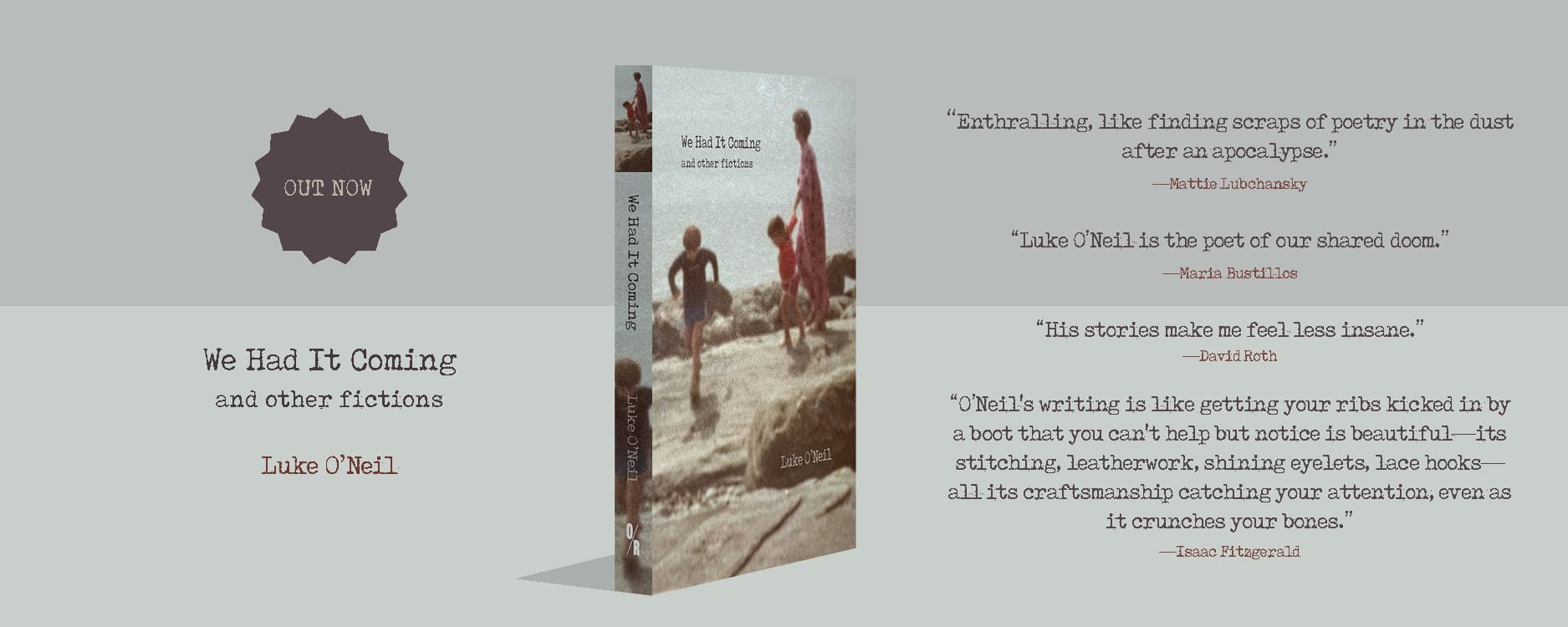

By the way please also consider pre-ordering (15% off) my forthcoming collection of stories and poems We Had It Coming. Sorry I hate being a salesman so much but that is part of the gig. No one else is really going to do it.

Be like this guy and his cat.

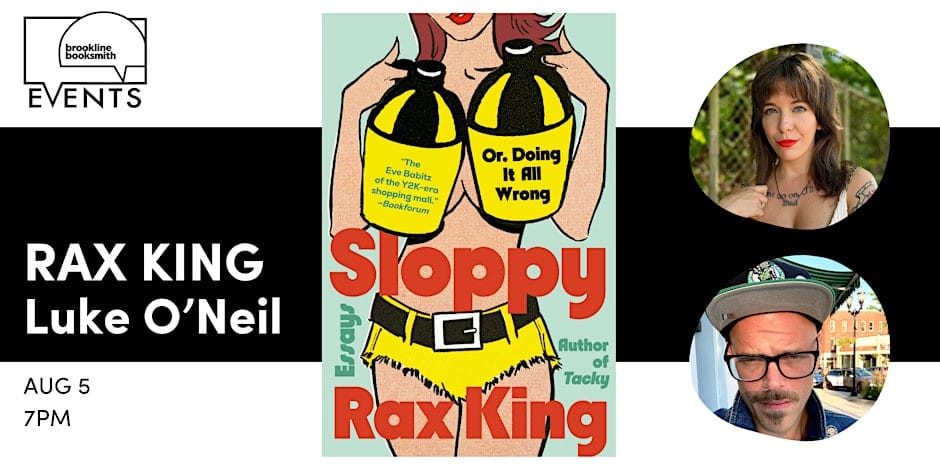

And while we're busy plugging come on out to this thing on August 5 where I'm going to talk to Rax King about her hilarious new book Sloppy, Or: Doing It All Wrong.

It’s the best feeling you can ever have in your life

by Dave Wedge

I first saw Ozzy in 1992 at The Orpheum in Boston with a young Zakk Wylde shirtless and shredding.

It was the height of the grunge explosion, but there was Ozzy and Zakk – in all their hair metal glory – playing “No More Tears,” with reckless Sunset Strip abandon, alongside all of Ozzy’s other hits from the previous three decades. It’s a show I think about often and it definitely changed me.

I was always a metal fan, but when grunge broke, the downtuned, melancholy music of Alice In Chains, Nirvana, Soundgarden and Smashing Pumpkins spoke to me in a very different, darker way. As if Sabbath’s death knell and war machine imagery were not dark enough, along came this less fantastical, more realistic, street level, punk metal. It was a natural progression from the 70s and 80s power metal of Ozzy, Judas Priest, AC/DC and Iron Maiden and was a very loud and pronounced rejection of the MTV-driven hair metal sleaze of Ratt, Poison and Cinderella.

But that show at The Orpheum – at the zenith of that cultural collision – reminded me that without Ozzy and Sabbath, there was no heavy music at all. It reminded me that powerful, emotional music endured, whether it was a Seattle junkie screaming for help or a blue collar Birmingham alcoholic shrouding his pain in Satanic imagery and chugging blues metal guitar licks.

When I heard Ozzy had died I cried. Just as I did upon learning of the untimely deaths of Freddie Mercury, David Bowie and Kurt Cobain. I didn’t know these guys personally. But they impacted my life as much as anyone.

As a journalist for the Boston Herald I was fortunate to have interviewed Ozzy several times. In 2010 he talked to me about his struggles with getting clean.

“I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, I don’t do drugs anymore. I’ve done all the drugs I’ve needed in my life,” he said. “It’s just good for me to be sober. Sometimes I go, ‘Yeah, a doobie wouldn’t be a bad idea.’ But then if I have one joint, next thing I’d be drinking beer for hours, then it’d be vodka and then it’d be coke. I know what will happen so I don’t go.”

He was honest with me about his hard won sobriety.

“I used to go, ‘How will I enjoy music anymore?’ he added. “But it still goes on. I don’t have to be a participant anymore. I don’t want to.”

I covered every Ozzfest that came through Massachusetts, each summer setting aside a day to go listen to metal bands old and new, all of whom were there only because of Ozzy. I have so many incredible memories of those days, traversing parking lots and hanging out backstage, experiencing the camaraderie, passion and excitement of the metal community created by Ozzy.

“When everything is in its right place and it’s going well and my voice is on form and, you know, and the crowd is giving me some craziness … there’s nothing in the world to come anywhere near – love, sex, drugs, there’s nothing can touch it,” he told me. “It’s the best feeling you can ever have in your life.”

As a hardcore New England Patriots fan, I’ll always fondly recall Ozzy’s surprise show at the season opener in 2005 at Gillette Stadium. Wearing a #1 Patriots jersey, he performed the teams’ longtime intro song “Crazy Train.” I really can’t recall a moment when I had more chills.

In 2010 he wrote a tell-all book that detailed orgies, Satan-worshipping, snorting ants and licking up piss with Motley Crue, and the true story of when he bit the head off two live doves in front of some record executives. I interviewed him about the book for the Herald and he was again completely unguarded and forthcoming.

“A lot of it I’m not proud of,” he told me of his notorious exploits. “But it’s only about what I remember. I didn’t want to do a book about how wonderful I am and how great it is to be the Prince of Darkness.”

When his final show in Birmingham – called “Back to the Beginning” – was announced a few months back, I knew Ozzy was struggling mightily, but few knew just how bad it was. I was skeptical about the show happening at all, especially after it was announced that he wouldn’t actually perform because he was sick. When the plan changed and it turned out that he would perform seated for a few songs, I was intrigued.

I’m happy I cast aside my skepticism, bought the all-day pay-per-view show and watched most of it live. I showed some of it to my 12-year-old son throughout the day. He’s not a huge metal fan but he’s learning to appreciate what I think is a uniquely tribal and deeply emotional and personal genre of music. He definitely understood the magnitude of the moment and the majesty of Ozzy. It’s something he’ll hopefully remember his whole life, much like I remember Live Aid and Lollapalooza and our parents recall Woodstock.

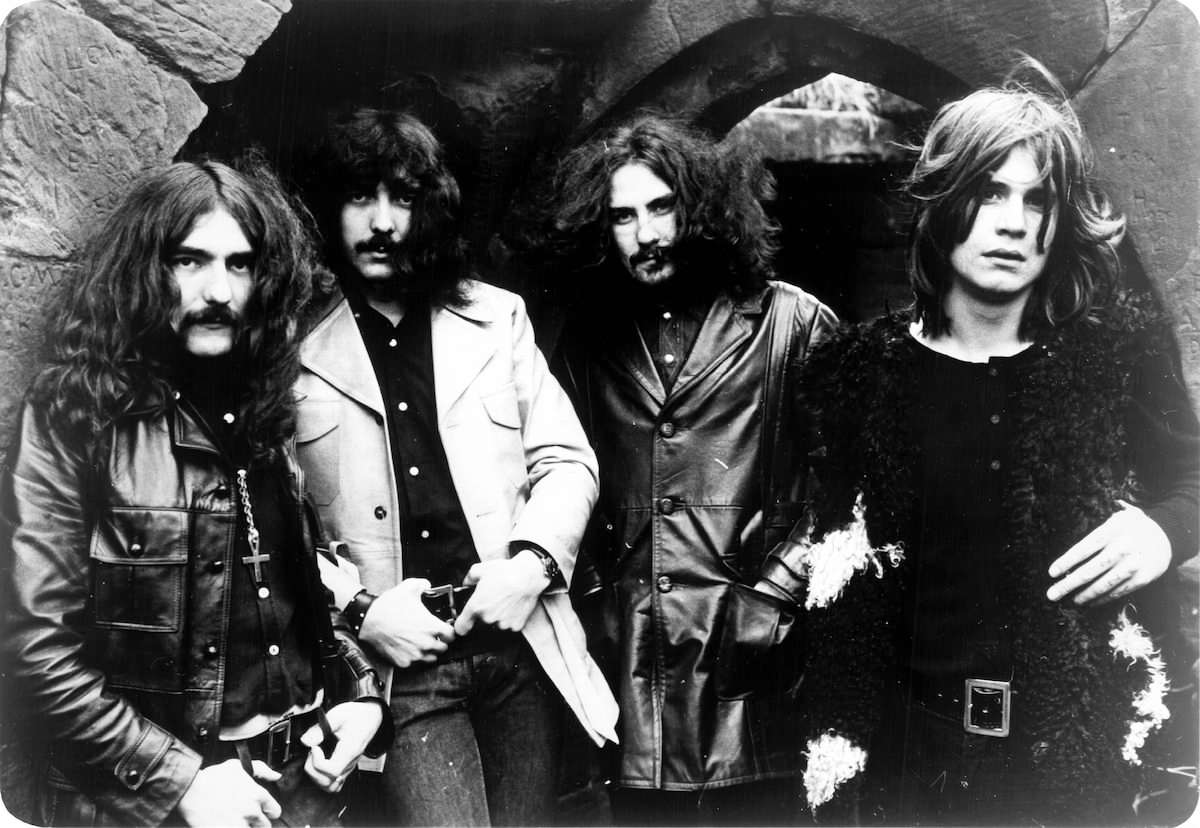

Metal and rock royalty paid tribute to Ozzy in Birmingham, where he, Tony Iommi, Bill Ward and Geezer Butler grew up and created this monster we call heavy metal. It was a truly historic day of metal that raised millions for charity and was capped by an emotionally-charged set by Ozzy that now takes on a whole new meaning. His impassioned version of “Mama I’m Coming Home,” was a highlight for sure. Now we sadly know that it was actually his final goodbye.

Like his songwriting partner, metal comrade and friend Lemmy before him, Ozzy died just days after his final show. It’s fitting. Guys like them have to go out guns blazing, and both certainly did, even if they were each weakened by illness at the end.

I’m grateful I got to interview him and witness his greatness up close and personal many times. In another interview I did with him in 2008, he summed up his persona perfectly:

“I’m pure – the crazy thing,” he said.

RIP Ozzy. Thanks for the insanity.

Dave Wedge is a New York Times bestselling author and former Boston Herald journalist. His latest book, “Blood & Hate: The Untold Story of Marvelous Marvin Hagler’s Battle for Glory,” was released in June and is in development as a feature film with Academy Award-winning actor/producer Sam Rockwell and actress Rosie Perez.

When will my reflection show who I am inside?

And what if it already does?

by Del Winters

Ah, will I gaze on my country’s shores, after long years,

and my poor cottage, its roof thatched with turf,

and gazing at a few ears of corn, see my domain?

An impious soldier will own these well-tilled fields,

a barbarian these crops. See to what war has led

our unlucky citizens: for this we sowed our lands.

– Virgil, Eclogues 1.1

You know when I came to this town after Korea, there was nothin’.

I brought the mall here. I got the 7-Eleven. I got the Fotomat here.

Christ, JCPenney is comin’ here because of me.

– Road House

Against a backdrop of picturesque old houses in Astoria, Oregon, two brothers comfort each other on the wraparound porch of their home, soon-to-be demolished for a country club. On a horse ranch in Jasper, Missouri, a salt-of-the-earth farmer glares across a canal to the man ruining local businesses with extortion, firebombs, and monster trucks to make way for chain stores and shopping malls. American fears over greed, corporate land grabs, and the disappearing small town way-of-life pop up again and again in 1980s and 1990s movies, from kid favorites like The Goonies (1985) to neon-violent cult classics like Road House (1989).

Degradation of the pastoral life by outsiders and the seizure of private property is not a fear unique to the last two decades of the last millennium of course. The ancient Roman poet Virgil bitched about losing land to soldiers returning home from war in 42 BCE. However, deindustrialization and deregulation in the 1970s and 1980s sharpened those fears to a fever pitch. Who Framed Roger Rabbit steamrolled the box office charts in 1988 by exploiting middle-class white American hand-wringing over eminent domain that mostly harmed working-class Black neighborhoods. By then, we were years into the Reagan administration’s dismantling of the New Deal safety net. In a country with robust participatory democracy, these fears could have been transformed into political leverage. Instead, as happens often in America, anxieties best answered through political organizing were instead only answered at the cinema.

If you're the protagonist of these movies, the person ruining your community is known to you. At your moment of triumph, you can tweak them on the nose or riddle them with bullets or rip up their foreclosure documents because they're there, physically, in front of you. As corporations snapped up more and more land and strip malls emerged as the dominant suburban life form, movies where neighbors and friends came together to save the town occupied less and less of the pop culture milieu. The fight was lost, and by the next decade a new villain had emerged, this time in the mirror.

I've worked in offices before, and they are a particular kind of crazy-making. I could predict the half-life of a break room donut down to the centimeter. I tapped the clacky buttons on the old school keyboard next to the printer just to feel something. I amused myself imagining the politely concerned face my coworkers would make if I suggested unionizing. I never considered punching myself in the face about it, but then again the donuts didn't emasculate me.

The job-induced ennui of the white American man fathered in black comedies like Clerks (1994) and Office Space (1999) and violent fantasies like Falling Down (1993), Fight Club (1999), and American Psycho (2000). After two decades of union busting, corporate layoffs, and cubicle purgatory, men emasculated by at-will employment and emptied out by morally bankrupt jobs were ready to let the intrusive thoughts win. What can you do when your true antagonist is nameless, faceless, and so far up the corporate ladder as to be as ever-present and ever-absent as God? You can't punch Reagan–not without Jodie Foster-induced limerence–so you might as well punch yourself.

The other option is to become a deity yourself, but it’s only available if you’re unknowingly an avatar of gender dysphoria like Neo in The Matrix (1999). Sorry about the self-inflicted bruises, Edward Norton.

Hostile takeovers ravaged Wall Street in the 1980s, emboldened by Reagan’s tax policies. Americans rejected the old consumerism of regulating businesses and embraced the new consumerism of purchasing on credit. American Psycho author Bret Easton Ellis created Patrick Bateman out of his own alienation and isolation triggered by the consumerist void of the time. Sure, the 1980s had movies about immoral suits like Wall Street (1987), but the protagonist redeemed himself at the end. The 1990s even saw Richard Gere and Danny DeVito play corporate raider love interests in Pretty Woman (1990) and Other People’s Money (1991). Only in 2000, when raiding had long fallen out of favor for institutionalized private equity, did the fear of being the corporate raider appear on the silver screen. These films rejected feel-good redemptive endings, embraced violence, and shattered the psyche of the protagonists. This trend might have continued unabated if not for the dot-com crash and the culture-fracturing shock of 9/11.

The post-9/11 landscape and aspirational wealth of y2k settled the question of whether you should really get so upset about your money that you get violent about it. No, it turned out, because making money is patriotic. Americans do love a story about a man torn between his morals and exorbitant amounts of money though. Sometimes these men get whisked off to action-thrillers like James McAvoy in Wanted (2008), which is more or less The Princess Diaries (2001) for desk jockeys, but mostly their anxieties about what to do if someone offers you a dump truck of cash manifest in serious dramas starring George Clooney like Michael Clayton (2007) or The Descendants (2011). Other entries include Thank You for Smoking (2005), 99 Homes (2014) and Promised Land (2014). Gone are the community victories of the 1980s, vanquished is the nihilism of the 1990s, and standing in the wreckage of the subprime mortgage crisis is individualism; the atomization of the suburbs perfectly replicated in the mind of the American man.

The term enshittification, the ratcheting up of customer extortion over time by online platforms owned by capricious billionaires, was coined in 2022. That same year, three fat-cat-and-mouse movies were released: Glass Onion, Triangle of Sadness, and The Menu. If Edward Norton's the Narrator in Fight Club is you as both protagonist and antagonist, then what to make of Edward Norton's Miles Bron, the capricious billionaire antagonist of Glass Onion? Now, we no longer struggle to identify our corporate overlords, because they can’t help but announce themselves. Despite his newfound corporeal form, the villain is more untouchable than ever before. He leverages our desires for dominance and career prospects against our morality, betting that we will continue to buy what he's selling as long as he controls everything.

What are you afraid of? How does the story end? The answer to the first question is difficult to see clearly, and the second is unknowable. We turn to stories to understand ourselves. As more filmmakers from a wider swath of humanity tell their stories, the trends change, they rhyme, and sometimes they converse. The Invitation (2022) preys on class anxieties but also weaves in race and the kind of marital fears found in Get Out (2017) and Ready or Not (2019). In the 1980s, white families fretted about losing private property; in the 2010s and later, Black characters fought against becoming private property through forced marriage or enslavement. Other movies from the 2010s grapple with the housing policy failures and hustle culture created by neoliberalism, such as The Florida Project (2017) and Parasite (2019). Some non-English language films fall outside these decade-long trends, too. Leviathan (2014) and As bestas (2022) are concerned with land disputes and private property, just like American films in earlier decades, although their resolutions don’t repeat the communal victories or morally redemptive antics of the 1980s. Monkey Man (2024) from actor-director Dev Patel is a revenge rampage against a police chief and a Hindu nationalist who killed the main character’s mother and built a factory over the remains of his pastoral childhood home. In the end, Monkey Man rejects going high for the finality of going low.

Small towns decay, corporate suits raid, and oligarchs play. The movies reflect our fears back to us long after the opportunity to prevent our fears from materializing has come and gone. It can be tempting to look at specific movie trends and see a cause-and-effect from box office returns to political outcomes, but the reality is often more complex and context-dependent. Movies are a reaction to outcomes created by political realities of years past, but they can also reinforce individualism over collective action. Stories with main characters tend to do that. The solution to the cult of individualism is not a different type of movie – it’s a different type of politics that prioritizes community-building, organizing, and, yes, media literacy and education. Cool guys with slick hair and sharper jawlines don’t go around kicking the shit out of the JCPenney’s man. In lieu of consequence-delivering cowboys, perhaps we could all organize something in addition to a trip to the movies, like a neighborhood block party, or a workplace, or even a country. Who knows, maybe one day they’ll make a movie about it.

Del K. Winters is a freelance writer who pens essays for MovieJawn and the love of the game. You can find their work at AbsoluteReality.blog. She lives in the best city ever, Philadelphia, with her partner and two-point-five cats.