People who hadn’t yet sold out

Today I'm proud to present an excerpt of A Clean Hell: Anarchy and Abolition in America’s Most Notorious Dungeon by Eric King (PM Press, January). It's a harrowing but steadfast look inside one of the most notorious prisons in America one of the most punitive and carceral countries in the world. I had to put it down a few times to take a break. Then I'd cool off and pick it back up again. Despite most of us knowing how violently and in fact criminally we treat millions of incarcerated people in this country it's another thing to see it written about as viscerally as King does here. You can read it here or down below.

First some thoughts on the passing of an old friend and the death of alt-weeklies. This piece can also be found here.

He gave a lot of opportunities to a lot of writers

I’m tired of writing eulogies. How many eulogies can a man write in a year? In a lifetime? And now I’m getting closer to fifty. I can’t begin to imagine how much worse it will get.

“Let’s not kid ourselves, it gets really, really bad,” as the song goes.

I think maybe this is why I had such a visceral reaction to watching The Long Walk the other day. Recognizing that that is simply what life is.

I know all of that man. You don’t need to tell me that.

You start off not really believing that it’s ever going to happen to you though. You suspect it will but you do not accurately grasp it. Then, if you’re lucky, one by one everyone else around you falls. They say in the movie, and in real life, that it’s the memories you share along the way that make the suffering all worth it. The friends you spend time with. The love that is created out of nothing. But I don’t know if I believe that now or if I ever fully believed it.

I don’t really have a choice though do I? That is the best deal we have ever been offered. It doesn't stay on the table forever either so you’d better take it soon.

I don’t know how old Jeff Lawrence was when he died sometime this week. It’s a funny thing that happens over time. You all sort of catch up to each other. It evens out and no longer matters. A person is either a little bit younger or, like him, a little bit older than you are. Until they die that is and then we all go oh my god that is too young. Too young to be dead. Too young to have died.

Jeff founded a magazine called Shovel in Boston in the 1990s which later became the legendary alt-weekly The Weekly Dig in 1999. For most of its run it wasn’t just the alternative to the Boston Globe and Herald it was the younger, hipper alternative to the other venerable alt-weekly the Boston Phoenix, all of which I would write for at one point or another. It outlasted the Phoenix too, finally closing up shop after changing hands a few times in 2023.

24 years old isn’t bad for a publication. Still too young to have died though. To have been killed I should say. We are all so much poorer for its loss and for the loss of alt-weeklies everywhere. Places where old fuck ups who thought they had missed their chance or young hungry idiots with no bylines to speak of could get a start. Not in spite of those things but because of them. People who weren’t yet turned and twisted by working in the normal media. Who hadn’t yet sold out. I know we don’t really say that kind of thing anymore but maybe we should start again.

“I have memories when the Dig was the publication I hated to pick up,” a former Globe editor just posted on my Facebook. The site where we pretty much only go now to talk about the dead. “And yet I always picked it up. The mark of a good thing and a legacy to be proud of.”

In those early internet days, pre-Gawker and so on, before everything we take for granted about social media now, alt-weeklies like The Dig were the only place you could go to see the major media being taken to task. Local scumbags being brought down a peg too. Or promoted depending on the kind of scumbag they were. But everything we wrote back then was so fun, and so funny, that people still often wanted to see how they were getting burnt. A kind of honor in a way.

Not to mention they were the best or only place to learn about bands and artists and books and restaurants that wouldn’t ever get coverage anywhere else. I never would have become the writer, or person, that I am today if not for picking up the Boston Phoenix at my suburban convenience store when I was a kid. A kind of community was built by papers like these and a kind of community was lost when they went away.

A lot of that in Boston was due to chances taken and gambles made by Jeff. Oftentimes very stupid ones. Sometimes ones that paid off.

"My grandmother died, and she left my father some money," he said in this oral history of the Dig written by Barry Thompson a few years back.

"I got $40 grand. So I went swimming at the Somerville YMCA – I love to swim – and then afterwards, I was sitting in a hot tub. I was still really trying to find my place in this world in my mid-20s, and was like, 'I need to do something.' Shovel had become successful insofar as people were calling me up and buying ads, but I had no clue in terms of publishing. I had a background in journalism and working for a college newspaper, but I didn't know the inner-workings. I don't have a degree in business. But all of a sudden it just hits me; 'The fucking Phoenix has no competition! I need to start a weekly!'"

He hired me for my first real job in journalism at the Dig as a books editor and then the music editor in the early 2000s. I must have been around 23 or so. He fired me from my first real job in journalism too. I will never forget he and Joe Keohane, the editor at the time, who I was just emailing dark jokes back and forth with a moment ago that I think Jeff would appreciate, walking me over to Foley’s on East Berkley St. and saying it was time to let me go. I had been calling in all the time and staying up late partying and partying all day in the office and it was taking its toll on my focus on the job. Never mind that a lot of that partying was done with Jeff in the first place! It was that kind of office. Kegs on tap. Clouds of weed smoke. Sex workers loitering around trying to place classified ads. Me leaning out the window to rip butts. The smell of the industrial bakery next door permeating the neighborhood – a sort of no man’s land of not-quite-Southie at the time. I can only imagine how many more high rises have gone up around there by now. Luxury condos.

“I had my first internship there in 2001 and it made me feel like the coolest person in the world, like I was walking onto a TV show set when I came in,” another friend just posted. “I remember Jeff as well, and the Dig, and thus him, really shaped my life.”

It was a job I was being paid $20,000 a year for with no benefits by the way.

That’s probably a good call I said when they fired me. Then probably asked if they wanted to go to the bathroom.

It was a good call. I wouldn’t have gone on to many of the things I went on to do if Jeff hadn’t given me that first opportunity to work and that next opportunity to go figure out how to do it elsewhere. Dozens and dozens of people in both the Boston and national media are saying the same to me this morning.

“I am in absolute shock,” another friend just posted. “Jeff was a friend, editor, boss, and someone who brought me into Dig Boston which really ended up being a turning point in my life. There was no one like Jeff and I just can’t believe it right now.”

“He gave a lot of opportunities to a lot of writers and creatives, including me. His legacy is large,” another wrote.

Aside from Boston journalism he was an early force in cannabis activism in Massachusetts, working on various advocacy groups and throwing yearly conventions, as well as helping to spread the word on craft beer back when that wasn’t really a thing. Beer Advocate was born in the pages of the Dig back in my day thanks to the support of Jeff and others.

Oh fuck my doctor’s office just emailed with some test results.

Hm. I guess nothing bad jumped out at me but I don’t know how to read these numbers. Now I have to wait for them to explain to me what they mean whenever they get around to it. Tell me what I need to do. The thing I already know. The same thing Jeff tried and failed to do for many years.

I talked to or texted with a bunch of other friends and colleagues this morning and we all basically said the same thing about our old boss: He was a pain in the fucking ass but we cared about him anyway. All these years later. Even after he fucked a lot of us over. Fired us or didn’t pay us what he owed. I remember him trying to pay me for work with gift cards, sometimes expired, for a while there when I started freelancing for the Dig again years after being fired. I know my experience wasn’t unique. I’d say fuck you pay me and he’d say he would and then we’d laugh about it and get a beer and bullshit about the Patriots. Then I’d get pissed off again and nevertheless still keep going back until I didn’t anymore.

It sounds abusive but it wasn’t I promise. I don’t know what it was though. How does that work? Charm I suppose. But his wasn’t some kind of typical magazine publisher’s slick charm. It was something else. Kind of like a fuck up older brother maybe. A guy you would often think “come on man get it together” about while still wanting to impress him. He was a figure with a considerable influence in the Boston media for a time but a person who was himself harmless.

Unless he was harming himself. Which I gather is how he came to pass. Too young however old it was. I’ll miss you man. Thank you for everything. I’m sorry for all of our losses. Fuck you. Pay me.

Anarchy and Abolition in America’s Most Notorious Dungeon

A Clean Hell

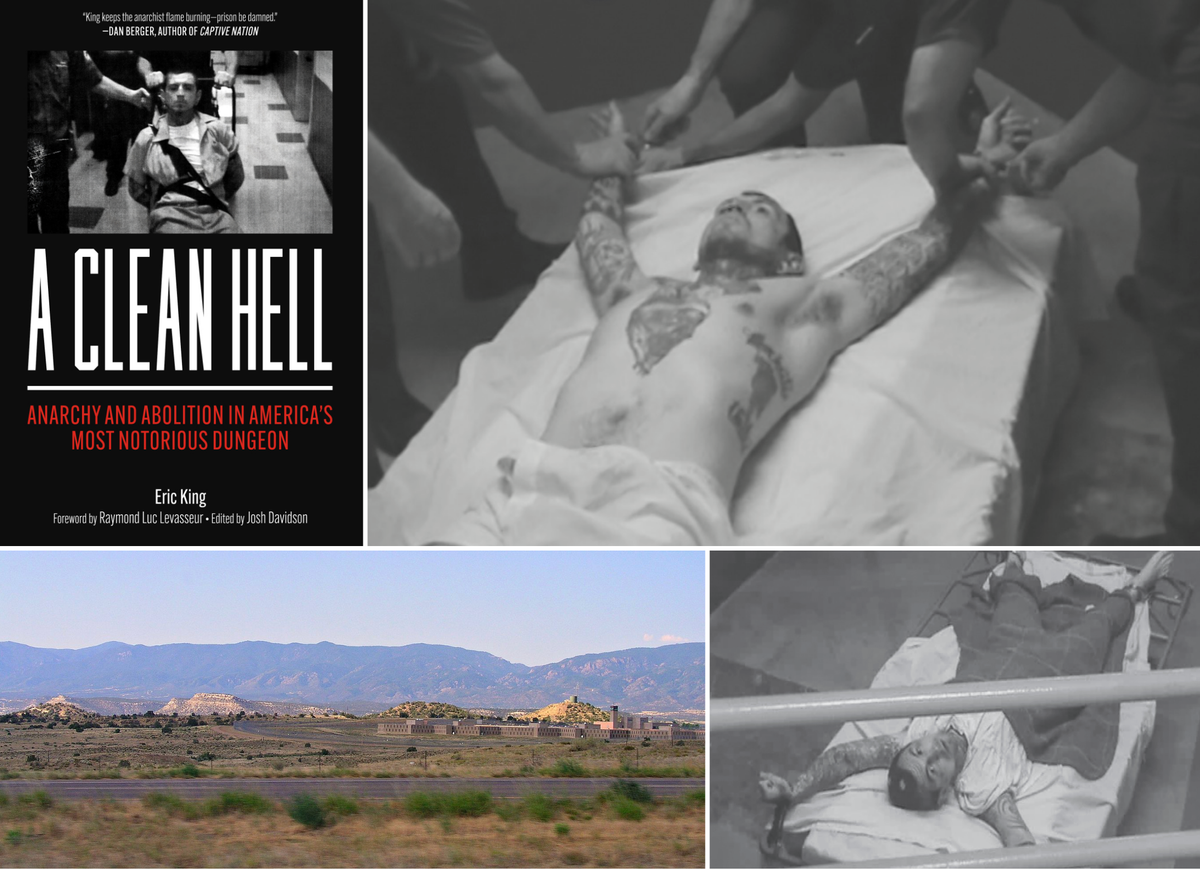

PM Press describes A Clean Hell "as a searing firsthand account from inside the most repressive prison in the United States, a place built not for rehabilitation but for disappearance."

The federal supermax ADX Florence is the most secure facility in the United States, a dungeon of isolation, sensory deprivation, and psychological disintegration. Here, cruelty isn’t accidental; it’s the design. Built in 1995, the “Alcatraz of the Rockies” was made to cage the so-called worst of the worst: bombers, gang leaders, political enemies, and anyone the government deems too rebellious, too inconvenient, or too visible.

Among them was antifascist prisoner Eric King, targeted for his politics, brutally tortured by the Bureau of Prisons, and ultimately entombed at ADX after beating a politically motivated federal prosecution. A Clean Hell tells the story of Eric’s decade behind bars: the years of surveillance and retaliation, the years locked in solitary confinement, the reality of being known as a “race traitor,” and the daily acts of resistance that kept him—and others—alive.

More than just a firsthand survival story and exposé, this is a blistering indictment of the carceral state and the sanitized violence it tries to hide. A Clean Hell is a crucial document of solidarity and struggle inside the belly of the beast and required reading for anyone concerned with mass incarceration, political repression, or the inhumane architecture of the US prison system.

It Started with a Joke, or How I Ended Up in ADX

by Eric King

There is a time when nine guards are beating you mercilessly that you may ponder, Am I going to survive this? When you start blacking out from their knees being pressed deeply into your lungs, you might think, I may not ever take another breath. When you are strapped to a chair and carried down a flight of stairs leading to the basement chamber, you will be justified in fearing, They are going to throw me down these stairs. When they stand you up against a wall and use metal shears to slice off all your clothing, you will certainly think, These motherfuckers are going to rape and kill me. Finally, you are forced onto a metal bed, your legs forcefully stretched as far as they can go, chained to the corners of a steel mattress. Your shaking arms are cuffed above your head, pulled so violently you know for sure they will get wrenched out of their sockets. Your body is now a vulnerable human X, completely and totally at the whims of your attackers. Your hands numb, your feet numb, your chest and back radiating pain in ways you cannot describe or have ever imagined feeling. While being brutalized, you may think, This is actual torture. This is literal torture. I may not make it out of this.

When the FCI and ADX captains come in to tell you that they plan on having you raped, beaten, and destroyed at your next location, oddly proclaiming, “This is street justice,” when those same captains place a plastic shield over your face and torso and push on it, forcing all the air out of your lungs, suffocating you, and when one of those same captains places his hand over your mouth for twenty seconds that feel like twenty hours, you will know for sure that you are going to die here. What happened to me is called four-pointing, because your legs and arms are chained to the four points of a steel frame. In the past, it was called quartering. Seven and a half hours of not moving a single muscle, of staring at a fluorescent light bulb, of trying to find any sort of peace within the agony. There is nothing you can do but feel it. Screaming will make no difference. No one who cares will ever hear your pleas.

You will urinate on yourself. You will lie in a puddle of your own piss and know that your torturer is doing this to break you. They want to degrade you, humiliate you. Everything in prison is about breaking our bodies or spirits. Struggle all you like, but that will only stretch and pull the muscles farther. Every minor movement causes fire to race through your body. All you can do is come to peace with your misery. This is my life now, nothing but unstoppable pain. Years later, you still won’t be able to feel parts of your hands. You will still have pain in your shoulders, back, and neck. You will still cry when you think of the powerlessness. When you reflect on your inability to stop the attack, you will feel panic in your chest, tears racing down your face. It wasn’t your fault. You didn’t do this to yourself. It is their crime, their inhumanity. You will come to understand that later, but at the time all you can do is suffer and feel it.

Michael Brown was eighteen years old when Officer Darren Wilson murdered him. He was barely old enough to vote, yet he was old enough to frighten the officer into pulling out his pistol and opening fire.

The streets erupted, justifiably so. The people of Ferguson forced the world to see and experience their sorrow and anger. What are you supposed to do when children in your community are being murdered and no one is being held accountable? I don’t know what you’re supposed to do when you see this sort of heart-wrenching drama play out, but for me and many others, the only option was action.

Countless people from Kansas City made the four-hour drive across Missouri to the battle zone. Some went to observe the wreckage, making uprisings a spectator sport, the tragedy less interesting than the spectacle. Others went to take control, treating the community like a group of children to be patronized and led. Many, though, went to offer a hand. To pass out water, to bring supplies, to be another body on the front lines. Not as leaders or warriors, but as allies and comrades. That was my brief experience. Carpooling with three strangers, listening to “Shake It Off” to calm our nerves. We needed to counterbalance the force of the state. The National Guard was there. The cops were there. The militias were there to support the cops. All brothers-in-arms.

While there, witnessing the hatred displayed by the authorities, I’d seen enough. When I returned to Kansas City, I couldn’t shake the unforgiving guilt I felt. While I was sleeping peacefully, they were mourning and battling. There were no stun grenades going off on Charlotte Street in KC. There were no armed militias in downtown Westport. Our privilege sickened me, and it was hard to swallow. Our streets didn’t smell like tear gas, and that didn’t seem right. Who were we to have such peace? Kansas City was sleeping with angels while Ferguson was battling with demons.

My actions started small. I didn’t want to lead a mass movement; for me, this was a personal revolution. I saw myself as a serious revolutionary. There are a thousand ways to sabotage the police state, and I thought I was Alexander Berkman. I was not clever. I knew nothing about security culture outside of wearing masks and gloves. On September 11, 2014, I wanted the people of Ferguson to know that someone, somewhere in Kansas City, remembered them and was in solidarity with them. They deserved to be fought for. If their lives and freedom were on the line, didn’t my solidarity demand the same of me? My life was not more valuable than theirs. My freedom was not more precious than theirs.

Bottles filled with Styrofoam, lighter fluid, and gasoline changed everything for me. They didn’t burn the brick building down, but they did turn my life to ash. Those two Molotovs and my lack of any precautions led to me being arrested and sent to a private jail in Leavenworth, Kansas. I wanted to go to trial but others convinced me it was the wrong idea. Signing the guilty plea was one of the worst feelings I’ve ever experienced. Total surrender and defeat. That led to me being sentenced to 120 months in the Federal Bureau of Prisons. I was sent to one of the easiest and weirdest yards in the BOP, FCI Englewood (FCI stands for Federal Correctional Institution), a low-security prison in Littleton, Colorado. This was a very short engagement. Within months, I was transferred up a custody level to the medium-security FCI Florence. I had drawn stick-figure cartoons the administration found threatening.

I never knew how bad it could get. I thought I knew. I thought I was prepared. I had no clue. I knew I would face repression. I knew there would be restrictions and cruel cops. But what came was something entirely different. I was a naive child, but reality has a way of teaching cruel truths, and I would learn them the hard way.

On August 17, 2018, my life changed forever. At around 1 p.m. at FCI Florence, I was called down to the lieutenants’ office to discuss an email I had sent to my wife. Instead of going into the office to talk over threat assessments, I was escorted into a mop closet. There are no cameras in mop closets. There are no windows in mop closets. This is a place to carry out violence. While in the camera-less closet, I was confronted by an enraged Lieutenant Wilcox. I was shouted at, spit on, threatened. I made a decision, a decision that has affected me ever since. I laughed in his face. I laughed at the veiny-necked, juiced-up, overconfident, sewage-breathed lieutenant who was actively threatening to batter me. His response was something I had never expected to happen, though I should have. I was pushed, I was punched, and then I was punched again.

Our lives are made up of massive moments that are birthed from tiny, insignificant ones. I sent an email, I laughed, I threw three punches to his bulbous face. I fought back. I struck down a member of the federal government. A chain of events that led me to the hardest times you can possibly imagine.

When you are in prison, there are times you may be challenged by an officer. You will have a personal feud, and the guard will have to prove how big of a man he is. He will take off his work utility belt, put down his walkie-talkie, and give you a “fair one.” This is usually a one-on-one fight, and after it’s over, the beef is over—no write-ups, no discipline, you just move on. These are rare, but they happen. Sadly, this wasn’t that. Florence cops are well-known badged thugs. They have been sued countless times for gang-beating, sexually assaulting, and torturing prisoners. They are cowards. They are petty, they are schemers, and they have as much dignity as a puddle of mud.

There are also times in prison when you learn that you cannot let yourself be a victim. You learn that you can’t appeal to pacifism when people plan on crushing you. Any holier-than-thou, I’m-above-it-all morality needs to be checked at the door. You cannot let someone push you, punch you, or attack you. After all, your life is on the line. People die in prison. The only person who will fight for your existence is you. You have to make split-second decisions, or your inactivity could be the end of you. There is no time to ponder the consequences of your actions. You must just survive. The only way to win at prison is to get out of prison. You have to survive.

The three punches I put all my might into busted Lieutenant Wilcox’s face to bits. His nose sprayed blood, his head shot back, and his body collapsed onto me and then onto the floor. He had picked the wrong one. I’m not the victim type. A blink of an eye after he collapsed, I knew this had only one ending. Slammed on the floor, stomped to oblivion, chained to a steel bed, suffocated, tortured. This is the price someone pays for defending themselves in the Bureau of Prisons, an institution where you are expected to lie down and let people who outweigh you by fifty pounds batter you. You are expected to be the ultimate victim. Take your abuse and humble yourself before us. I was not prepared for the next six months, the next five and a half years of continual segregation. A half decade of constant transfers, of absolute restricted communication, of violence upon violence. I should have seen what was coming around the bend. I was very naive then.

Almost a year to the day after the attack, I was flown to FCI Englewood and immediately placed in a six-foot-by-eight-foot cell within the SHU (Special Housing Unit). Two days later, I was taken to court. I was being prosecuted. The FBI had taken up the case and charged me with assaulting a federal employee and causing serious bodily injury. The prosecutor was asking for the highest possible punishment: twenty additional years within the Federal Bureau of Prisons. My assault was an attack on them, and they wouldn’t stand for it. Any self-determination within the walls is seen as a bad thing, but standing up for yourself physically is the most dangerous game. They didn’t want to choose a misdemeanor, they wanted blood. They wanted my future. They wanted to ruin my wife’s life, my kids’ lives.

I would not claim any guilt for the horrendous crime of not letting a federal thug beat my head in. I would not entertain any plea deals, and there weren’t any offered. I was going to trial.

Excerpted from A Clean Hell: Anarchy and Abolition in America’s Most Notorious Dungeon by Eric King out in January via PM Press.